John Fitch is a genuine American hero, and a survivor. If they made a movie about his life, Jimmy Stewart would have played him. You know, a handsome, lanky six-footer, thoughtful, modest, brave and true in the face of a challenge or worthy cause. Truth is, Fitch has been accepting challenges all his life. Indeed, he’s openly courted danger, but interestingly, a basic decency has almost always elevated his personal adventures to something higher than just thrill seeking. Hero stuff.

At nearly 83 years young, John Fitch is going strong as one of the leading authorities on motor racing safety, particularly in the area of energy-absorbing systems for the walls of race tracks. Thousands of lives have been saved by the now ubiquitous bright-colored, plastic, energy-absorbing barrels seen protecting danger spots on highways all over North America. They were, of course, invented – and personally tested – by Fitch. He’s always been a pioneer, it seems. Fitch won the first 500cc (Formula Three) race in the U.S. He was the first SCCA National Champion. He was the first American to win an international sports car race abroad (with a Cad-Allard in Argentina). That resulted in a call from American sportsman Briggs Cunningham, offering a ride at Le Mans in 1952… the big time.

By the 18th hour, Fitch and codriver Phil Walters had their white and blue Cunningham cruising in second place, but engine problems put them out. At Sebring the next year, Fitch and Walters won the first ever Sports Car World Championship race in a Cunningham. At Le Mans, a brilliant if ultimately unsuccessful drive in the Cunningham (where Fitch led away at the start only to have a coil lead fall off, then clawed his way back to third by the fourth hour before blowing another engine) caught the eye of Mercedes Benz. Fitch impressed in a test at the Nurburgring two months later and began lobbying for Mercedes participation in the Carrera Panamericana, ultimately persuading legendary team leader Alfred Neubauer that it would be good for MB sales in America if a Yank drove for them in Mexico.

Mercedes did compete in Mexico in 1952 (they won) and Fitch got his ride, in the process becoming the first and only American ever to drive for the Mercedes-Benz works team. In spite of repeated delays with alignment-related tire problems, the “amateur” Fitch finished fourth, but due to erroneous instructions from a local race official, ultimately was disqualified. But he had led the race at one point and been fastest of all on the final leg. It was a good performance and would be remembered by Mercedes-Benz.

For John Fitch, 1953 would be a turning point. At Sebring, he and Walters won the first ever Sports Car World Championship round in an American Cunningham. There was a short, disastrous run at the Mille Miglia. Fitch’s Nash-Healy caught fire just before the start and not long after, suffered a brake failure (a broken line). This was followed by a third place at Le Mans with Walters, the first time any American had ever made the podium, a frightening 140-mph crash in the Cunningham while leading at Reims, a perfect score (the first for an American) in the Alpine Rally driving a works Sunbeam-Talbot, and several other European rides, among them, a fourth-place finish in a Cooper-Bristol in what would be Fitch’s first Grand Prix. What’s more, he got paid $228 for this drive. At home, sports car racing was a rich man’s game, and strictly amateur – or it was supposed to be. Now living in Europe, John Fitch became the first American-born “professional” racer to ply his trade abroad.

Ironically, Fitch would earn much more in Europe as technical advisor for a Hollywood movie, The Racer, than he did as a driver in 1954. But early the following year, he received a telegram at his Switzerland home from Alfred Neubauer offering a works Mercedes ride for the 1955 Mille Miglia alongside Juan Fangio, Stirling Moss, and Karl Kling. The latter would drive the awesome new 300 SLR racing cars, Fitch, an early production 300SL coupe to contest the GT class.

Fitch and British journalist Denis Jenkinson had hoped to do the Mille together, but when Moss was hired by Mercedes-Benz, plans changed.

Fitch recalls, “It was Stirling’s first race and both of them wanted to have an all-British team. They were good friends, anyway. They asked if I would release Jenks, and of course, I did. And Mercedes got me a young journalist from Hamburg.”

The problem was, Fitch’s assigned co-driver was not going to be much help, having never so much as seen a motor race. Kurt Gesell wrote for a German magazine called Hearing & Seeing and was at the Mille Miglia to personally experience the sport. And indeed he did.

“He’d learned some English from U.S. soldiers stationed in Germany. We had a 180 Mercedes, a little four-cylinder 1800cc four-dour sedan – you can imagine, maybe 73 hp – that we drove around the circuit before the race. I knew we were in trouble when he told me afterwards he just couldn’t imagine anyone going any faster than we did. I mean, this pokey sedan probably did 85 mph, downhill!”

With Jenks, Fitch would have had the benefit of detailed pacenotes on a clever roller (a Fitch idea Jenks would use with Moss), but Gesell would be capable of communicating only the simplest warnings about real danger spots. Undaunted, Fitch was prepared to give his best effort, even asking Neubauer if he should be contending for an overall top finishing position.

“He just roared with laughter and patted me on the back, saying, ‘No, no, you just worry about the GT class.’”

The fast young Belgian ace, Olivier Gendebien, also in a 300SL, was expected to be Fitch’s greatest threat in the GT class. And so he was, but Fitch led all GT cars at Rome, in spite of a high-speed miss. It was not an easy ride for Gesell, however, who was awed – and often terrified – by the ferocious pace.

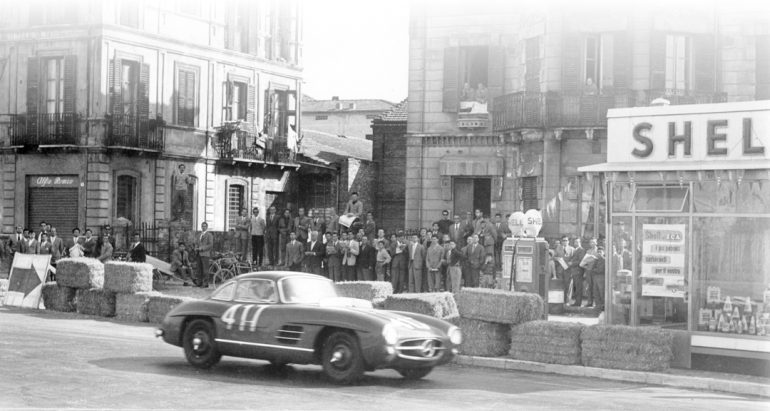

Fitch threw his Mercedes at the treacherous Italian roads, sliding around narrow blind mountain curves, leaping over hidden bumps, then crashing to the ground to careen onward, slicing through corridors of parting spectators near the cities, skidding down cobblestone alleys between buildings, then blasting full speed along crowned country lanes. “Mein Gott!” became Gesell’s most frequent contribution.

“It wasn’t very long into the race, instead of warning me about places that we had agreed he would signal me, he just froze up and said, ‘Mein Gott!’ We had some close calls, brushed up against some curbs here and there and got some real surprises. But especially in the high-speed sections, you really should know what’s coming up over the brow of the hill, if it’s a 50-mph turn to the right or just another straightaway. It’s very important.”

Poor Gesell also inadvertently pulled the straw-like tube out of their only water supply. Ventilation was another problem. The gullwing’s windows were clipped in for aerodynamic reasons and wind pressure at high speeds pinned the side wings shut. Heat and dehydration added to Fitch’s fatigue as he struggled to concentrate.

There was bad news at Florence. Gendebien had pulled ahead. The high-speed miss was worse now and top end was down almost 20 mph.

“It was something that happened only after running at full throttle for hours. Our top speed was cut from about 160 to 140 mph. I thought we’d lost the race.”

Gendebien was sure to gain even more ground in the final several hundred miles, where there were long, flat-out sections. It looked absolutely hopeless. Fitch would be prudent to back off and just consolidate his second-place position. Instead, he attacked ferociously, late-braking, pushing every corner, using every inch of road, in a desperate charge to the finish. It worked. Eleven-and-a-half hours after they’d started at Brescia, Fitch and Gesell returned to take the flag several minutes before Gendebien. Not only did Fitch win the GT class, but remarkably, he finished fifth overall, beaten only by Moss and Fangio’s 300SLRs, Maglioli’s Ferrari, and a Maserati. Only three minutes off Alberto Ascari’s overall winning time in the Lancia in 1954, Fitch managed to finish ahead of all the other true racecars, as well as his GT competition.

Because of Stirling Moss’ record win, Fitch’s heroic performance was largely overlooked in the British press in 1955, but it was certainly the greatest drive of John Fitch’s stellar career, not to mention the best Mille Miglia result for any postwar American racer.

Photo: John Fitch Collection