1980s Cars – A Time Of Excess, Big Industry Changes & The Rise Of Japanese Carmakers

The eighties took things to the next level in term of automotive design, quality and performance. The U.S market has also changed, with American automobiles being outsold by imports, notably Japanese cars. In the early 1980s Chrysler lost $1.7 billion in a single year; Ford lost $1.5 billion and GM $763 million. It was a reality that the Big Three had to face and the truth was hard to swallow. The Japanese, whose products were being derided by Americans a generation before, had done their homework and were producing cars that outperform American-made ones. It was a slow process that produced reliable, quality cars. In the early 1950s, Japanese automakers visited American plants. They learned what they had from American plants, absorbed the technology and then adapted it to fit their own society. They created massive auto factories where work was broken down into specific operations carried out by teams working together.

Automobile Model List (1980 - 1989)

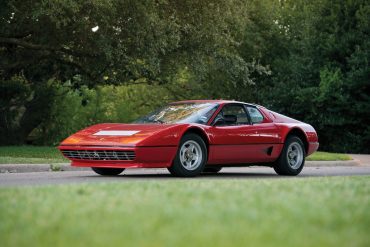

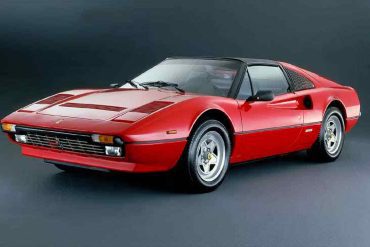

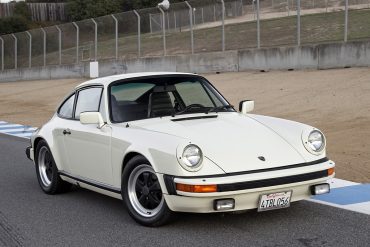

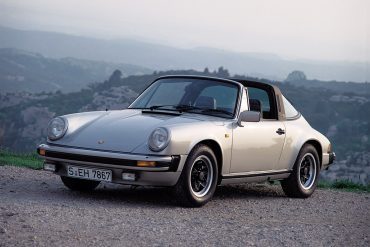

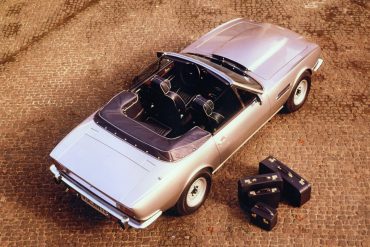

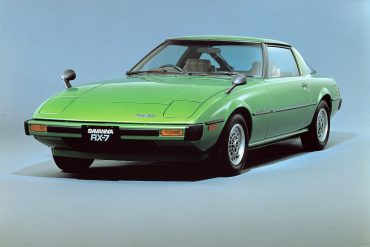

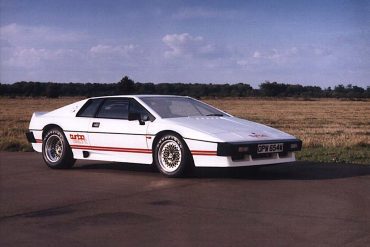

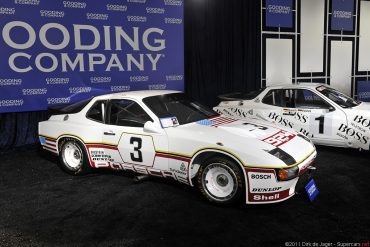

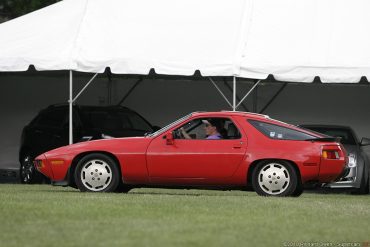

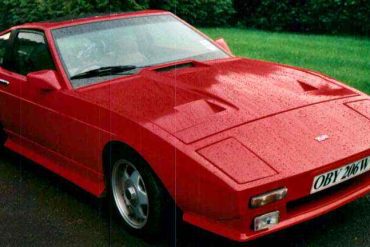

The 1980s saw a resurgence of performance and technology in the automotive world, as turbocharging became widespread, computer controls entered the scene, and iconic sports cars like the Ferrari F40 and Porsche 959 emerged. This era also saw the rise of Japanese automakers, who challenged established brands with reliable and fuel-efficient models, forever changing the global automotive landscape.

1980s U.S Car Makers

In the early 1950s, Japanese automakers visited American plants. They learned what they had from American plants, absorbed the technology and then adapted it to fit their own society. They created massive auto factories where work was broken down into specific operations carried out by teams working together. This was a departure from the way Americans produce their cars.

Massive Changes Play Out In The U.S

Big Three Fading

In the U.S., management and workers didn’t get along well. The auto unions fostered a distrust between them and management, hence quality of the cars they make wasn’t a priority with them but just a byproduct of their existence as employees. In Japan, there was not only mutual respect between supervisor and worker, there was also constant dialogue. Management valued the input of the assembly-line worker because he was closest to the production process.

The Japanese didn’t really invent anything. They used many of the existing technologies plus discipline in manufacturing their 1980s cars. The slide of 1980s automobiles in America was precipitated by the 1979 oil embargo on Iranian oil placed by the U.S. in response to Iran’s hostage-taking of American embassy personnel in Iran. For the second time in the 1970s, there were long lines and high prices at the gas pump.

Americans had realized that they had to shed their dislike for smaller cars, where they had to cram their big frames and bodies. Fearful of being unable to use their cars because of the gas shortage, they started buying the smaller Japanese cars. Precisely during that time, the Japanese started pouring their 1980s cars into the U.S. and people started buying them. Americans, who shortly before loved their big, thirsty American-made cars, discovered that Hondas, Nissans, and Toyotas were not only fuel efficient, but mechanically sound as well. That was the shift.

The slide of 1980s automobiles in America was precipitated by the 1979 oil embargo on Iranian oil placed by the U.S. in response to Iran’s hostage-taking of American embassy personnel in Iran. For the second time in the 1970s, there were long lines and high prices at the gas pump.

Americans had realized that they had to shed their dislike for smaller cars, where they had to cram their big frames and bodies. Fearful of being unable to use their cars because of the gas shortage, they started buying the smaller Japanese cars. Precisely during that time, the Japanese started pouring their 1980s cars into the U.S. and people started buying them. Americans, who shortly before loved their big, thirsty American-made cars, discovered that Hondas, Nissans, and Toyotas were not only fuel efficient, but mechanically sound as well. That was the shift.

The same derision for shoddy “Made in Japan” products turned to affection. Confidence in Japanese cars began to rise dramatically through a combination of advertising and word of mouth. Starting in early 1980s, the greatest recession/depression for the American auto industry happened. On the other hand, the Japanese were doing very well. In the meantime, by 1980 industry observers estimated that for every 100 American cars coming off the assembly line, there were 700 defects.

American drivers of 1980s cars made in Japan were getting used to a different kind of quality standard, the defect-free standard; the vehicle that almost never has to go back to the dealer for a repair. American car executives finally realized that to be able to compete with imports, they had to raise their quality and productivity, the standard of excellence in car manufacture, or they weren’t going to make it in the car manufacturing business. In the early 1980s, Chrysler was in bad shape compared to Ford and GM who had better resources.

Reagan And 80s Car Imports

With nearly two million Japanese cars and trucks sold in the U.S. in 1980, President Ronald Reagan wanted a level playing field in the American car market by demanding that Japan reduce its car exports to the US by 25% for at least the next few years. It was an unfavorable demand because the Americans receive one-half of Japan’s car exports. With the threat of protectionist legislation to protect the Big Three, Japan relented. This in turn helped to revive Detroit. By early 1981, the American automakers were showing profits again.

Learning from its mistakes and being helped by Reagan, the Big Three instituted investments like they never did before. Spending twice as much money, the early years of the 80s decade saw Detroit able to improve their cars. The gas guzzlers that rolled off were now more fuel-efficient. They were built with quality in mind. By the end of the decade, both Detroit and Japan were doing very well, with Japan still taking a market share of more or less about the same percentage as it had beginning the decade of the ’80s.

The 1980s For U.S Automakers

1980s U.S Carmakers

Ford hired Philip Caldwell in late 1979, the first person outside the Ford family to be named CEO. Still reeling from the Pinto disaster, Caldwell had to do something dramatic in manufacturing 1980s cars in order to save the troubled company. He mandated to make quality the number one goal of the Ford Motor Company. But not before losing $1.5 billion in 1980, $1.1 billion in 1981, and $700 million in 1982, a total of $3.3 billion in three years, an astounding figure for a company that had not reported an annual loss since World War II.

Although Ford had a profitable and respected line of trucks, among car owners, the company had become something of a joke. It was decided that the company needed something completely different: a midsize car that would be striking in both design and performance. That car was the Taurus. Conceived in 1980 and introduced in 1985, the Taurus was instrumental in reversing Ford’s decline.

Unveiled in January 1985, it was immediately popular. Dealers could not keep the 1980s cars in stock. It performed very well, it was smooth, efficient, economical, comfortable, and fun to drive. It was rounder, more stylish – it didn’t look typically American. It was at one time called “the hotdog” because of the sort of round shape but the shape was a blessing in disguise because it became a very distinguishing factor.

The Ford Taurus helped to lift Ford from its early 1980s difficulties. Ford committed $3 billion to the Taurus project. Even though Ford turned the corner before the Taurus was introduced, by 1986 profits soared to $3.3 billion. The huge popularity of the Taurus, coupled with renewed interest in the company’s high-end “Panther” cars (the Lincoln Continental, Lincoln Town Car, Ford Crown Victoria, and Mercury Grand Marquis) helped Ford earned $4.6 billion in 1987 and $5.3 billion in 1988.

Chrysler’s comeback was engineered by Lee Iacocca, a charismatic guy. Once working at Ford to bring the Mustang to profitability, he was hired by Chrysler to turn the business around. Virtually broke, the government bailed the company with an unprecedented $1.2 billion guaranteed loan. With Iacocca’s steady hand, the company slashed its workforce by half. With it’s line of K-cars – Dodge Aries, Plymouth Reliant, Chrysler LeBaron, Dodge 400, and, in Mexico, Dodge Dart, strongly performing, in the first quarter of 1984, Chrysler showed a profit of more than $700 million. At the end of that year, profit was $2.38 billion. Profit in 1985 was $1.64 billion. Its line up of 1980s cars, once again, were profitable. Lee Iacocca became a celebrity. By turning around a virtually bankrupt company, he went on to make $20 million in 1987. Life again for Chrysler’s worker was great.

GM made $4.5 billion in 1984, owned 44 percent of the U.S. market, but for all of that, made a series of miscalculations that proved its undoing. By the end of 1986, GM’s market share had fallen to 34 percent. Their 1980s cars were of low-quality. Management’s stubbornness in the decisions that it made caused the company to spend more than it was making. GM’s CEO, Roger Smith, relied on automation but the technology failed to deliver. GM’s million-dollar robots made more mistakes than its human workers.

The Pontiac Fiero, a tiny plastic sports car that looked great but had the tendency to burst into flames, was one of the company’s worst cars. In 1989 the company built more than 240,000 4-cylinder Fieros; each one was recalled twice!! Response was slow on its new GM-10 cars (which included the Pontiac Grand Prix, Chevrolet Lumina, and Buick Regal). Mechanical problems plagued the car. Sales were bad. Fortunately, GM was compelled to change its tactic. The management adopted the Japanese team approach to making its cars at its independent Saturn division. Saturn’s customer-friendly approach to selling them won customers over.

Roger Smith gained accolades from the press and awards from several publications and institutions. Described as an “innovator”, a “futurist”, and a “visionary”, the ambitious attempt to surpass the Japanese at their own game backfired: according to automotive research undertook by the UCLA’s Lieberman and Dhawan, each GM employee produced just 11.7 cars, while the same metric at Ford was 16.1 and as high as 57.7 at Toyota. GM also earned 38% less than Ford.

With GM’s spending calculated at $34.7 billion over the period from 1986 through 1989, with that amount, GM could have purchased Toyota and Nissan. This would almost double GM’s world market share, increasing its penetration over 40% of the entire free world. With Smith’s miscalculations and faith that robotics is the Holy Grail of auto building, it just shows that attention to detail and the ever-present realities.

1980s European & Asian Car Makers

The 80s car imports were dominated by Japanese made cars. Compared to American cars which were perceived as of lower quality with large engines that were not economical with gasoline, cars that were produced by Toyota, Datsun, and Honda, were well-built and came with engines that were fuel-efficient.

Also, they came at a lower price. No wonder that one out of every four cars sold in 1980 were imports. With the oil crisis triggered by OPEC’s decision to curtail production in 1979, the price of crude went up. Whereas prior to the oil crisis American loved big cars, now the focus of American buyers went to fuel economy. Several other countries vied for the American market: Korea, France, Sweden, Germany, and last but not least, Yugoslavia with its Yugo, not only the worst 1980s imported cars but of all time.

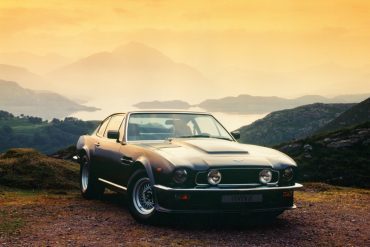

The Italian, German & French Carmakers

1980s European Car Brands

German-built cars gained a reputation for fuel efficiency. Volkswagen’s design, for one, as well as their functionality won Americans over Volk’s being fun to drive. Volkswagen’s executives also decided to put their engines on the front, rather than on the back due to safety problem concerns.

Saab, a Swedish aerospace manufacturer, also has had limited success in American markets. Saab, while gaining a following in Europe with its generally considered high-performance cars, hasn’t acquired the confidence on American buyers that German and Japanese imported cars had. Meanwhile, Volvo, another Swedish import, had earned American buyers trust because of the company’s focus on safety.

Even Yugoslavia went for the American consumers. Yugos, reputedly one of the 80s worst car came to America. Malcolm Bricklin, an American entrepreneur, was responsible for the Yugo’s introduction to American buyers.

After several modifications, the Yugo GV, one of the first five models, was introduced for the basic entry-level sub $4,000. The GV (Great Value) came with a glass sunroof, with the GVX coming with 1300 cc engine, give-speed manual transmission plus additional standard options.

The Japanese Carmakers

1980s Japanese Car Brands

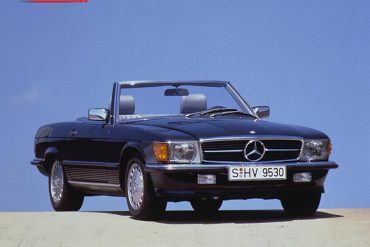

Having established themselves as makers of reliable cars and light trucks in the ’70s and in most of the ’80s, Toyota and Nissan debuted their luxury lines, Lexus and Infiniti in the late 1980s. By then, the German carmakers BMW and Mercedes-Benz had well established luxury cars. Initially skeptical of the Lexuses and Infinitis, the Japanese cars through the years had won over many American buyers.

By 2005, Lexus had surpassed BMW in total sales. These 1980s foreign autos had been ingrained so much in the American’s psyche that they’re almost everyone’s dream cars in addition to the Mercedes-Benz’s cars.

The Korean Carmakers

1980s Korean Car Brands

Korean manufacturer Hyundai sold the Hyundai Excel which had a reputation for being underpowered and poorly made. Hyundai manufactured the Excel from 1989 to 1986 and that first Excel was deemed as awful. But that 1.5-liter engine, four-cylinder engine car with a front-drive was comparatively cheap: they were priced at just below $5,000. In 1986 alone, Hyundai sold a lot of them – more than 166,000 units. Hyundai learned a lot from that first car which set the company up for the success that it enjoys today.

1980s Car Models - 350+ In Depth Guides

Here is a list of the important models from the 1980s decade