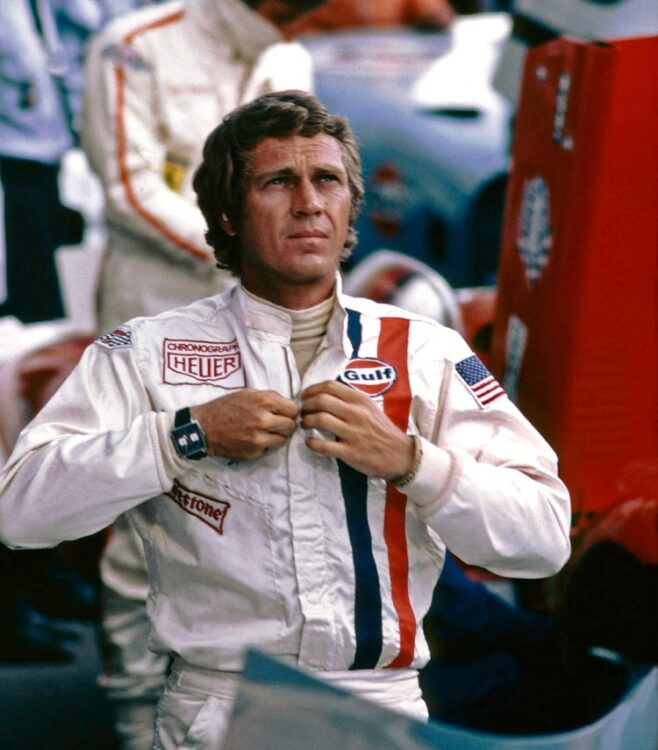

Can it be? Steve McQueen’s motorsport magnum opus movie turns 50 this year.

The film Le Mans was released in theaters on June 23, 1971. Certainly a heyday on the world stage of motorsport, most particularly big game sports car and endurance racing.

Ferrari, Jaguar, Maserati, Mercedes, and others dominated the 50s. Ford and Ferrari famously duked it out during the 60s. By the end of the 60s, Ford’s fabulous GT40 had pretty much run its course, Ferrari minted a new line of big gunners called the 512, and Porsche emerged from the ranks of GT level machines with a new 12-cylinder monster called the 917.

“Even as he was filming Bullitt in 1968, my dad already had visions of an epic racing film in his head, a super realistic immersive visual experience” recalls now 60-year-old Chad McQueen, his father Steve’s only son.

True enough; about the same time as James Garner was in production of Grand Prix, McQueen, and director John Sturges were in development on a film to be called Day of the Champion, also about Formula 1.

GP was slightly ahead of Champion production schedulewise, and would have certainly come to market first. McQueen’s producers didn’t want to be hitting theaters second with a film too similar in nature and concept, so the project was scrubbed.

It was inevitable that McQueen would revisit the racing film concept when the time was right, and 1969/70 was; McQueen was at the height of his star powers and had by then become a formidable sports car racer. Instead of another focus on the open-wheelers, McQueen cast his Solar Productions Company’s considerable attention toward international endurance racing.

His intent went beyond starring in the film – not satisfied to merely talk the talk; he intended to walk the walk by racing at Le Mans, teamed with incomparable F1 champion Jackie Stewart. Steve McQueen was thoughtful and philosophical about it;

“Well, I don’t know if I’m good enough. I want to see if I’m quick enough to practice for Le Mans, and if the drivers will accept me, I’d like to run in the [1970] race.”

It was decided, for a variety of reasons, that McQueen not compete in the 1970 race, and ultimately, Stewart didn’t either.

John Sturges went on to direct Le Mans and would begin by filming the actual Le Mans race, with story fill-in shots to be captured at the Le Mans circuit after the race.

As a bit of a compromise for not getting to race at Le Mans, McQueen would instead work as one of the high-speed action and stunt drivers for all of the post-race action footage needed – often at over 200 mph.

For this, Sturges, McQueen, and Solar assembled a formidable roster of racecars, several of which competed in the 1970 race, and professional racers to drive for the camera.

McQueen would star as factory Porsche 917 pilot, American Michael Delaney. Delaney came to the story with outstanding talent and more than a little personal and racing baggage.

Critically important was to authentically and dramatically capture the racing action’s sound, feel, speed, and sensation. To facilitate this, the camera crews used a variety of camera/sound equipment and innovated the specialist rigs, mounts, and equipment needed to get the cameras and mics up close and personal with the cars, drivers, and the competition.

Three camera-carrying cars were employed; Among them were McQueen’s own ex-Sebring 908 Spyder, which, equipped with three different cameras, actually ran the ’70 race. Its bodywork was configured to shield the cameras, fore, and aft. No matter, the tidy 908, ably driven by Herbert Linge and Johnathan Williams, kept up with the action, stayed clear of trouble, and finished an amazing 9th overall.

Among the trio of Porsche 917s that Solar Productions had under its command for post-race filming action, one of them served as a high-speed camera car, fitted with an innovative articulated camera rig that could be swung from side to side, allowing the cinematographers to capture high-speed action with the fastest of the cars.

Today this sort of rigging is common for action filming; it was unheard of for 1970. The Solar crew also used a reconfigured GT40 to chase down and photograph the panoply of Porsches, Ferraris, Corvettes, Matras, and others that appeared in the post-race action sequences.

It’s a bit of a miracle that the film was ever completed, given that the production was over budget, and behind schedule.

Filming began with a pretty thin script, so scenes were being written and rewritten every day, on the fly. McQueen and director Sturges were constantly at odds, so much so that one day, Sturges called a halt, and quit.

Lee Katzin replaced him. Amid the background noise was that McQueen’s marriage to first wife, singer/dancer/Broadway star Neile Adams, was disintegrating. Le Mans was completed and released primarily due to Steve McQueen’s sheer force-of-nature will and commitment to the project.

Of huge significance is the roster of then current pros who served as action and stunt drivers in the production; they include 1970 race winner Richard Attwood, Jurgen Barth, Derek Bell, Paul Blancpain, Vic Elford, Masten Gregory, Jacky Ickx, Jean-Pierre Jaouille, Gerard Larrousse, Herbert Ling, Herbert Muller, Mike Parks, David Piper, Brian Redman, Jo Siffert, Rolf Stommelen and Johnathan Williams, to name most.

Chad McQueen remembers every minute of his summer in France, with his family on the Le Mans set, surrounded by so many great cars and legendary drivers.

“My dad put me on his lap in the 917, and he of course shifted and worked the pedals, but I had my hands on the steering wheel, with his hands just ‘ghosting’ mine. I was guiding the car, but he was right there ready to step in if needed. We ultimately hit 100 mph, and I’ll never forget the sound, smell, sight and feeling of that moment, driving a Porsche 917 with my dad.

Five-times Le Mans winner Sir Derek Bell summarizes the film succinctly:

“Le Mans is a bit like a bottle of really good French wine – it may have been a bit tart when first vinted, but has grown and aged memorably with time, thus great to enjoy over and over again.”

[Photography Matt Stone and Courtesy of the Brumos Collection, Porsche Werekfoto, and the McQueen Family Collection]