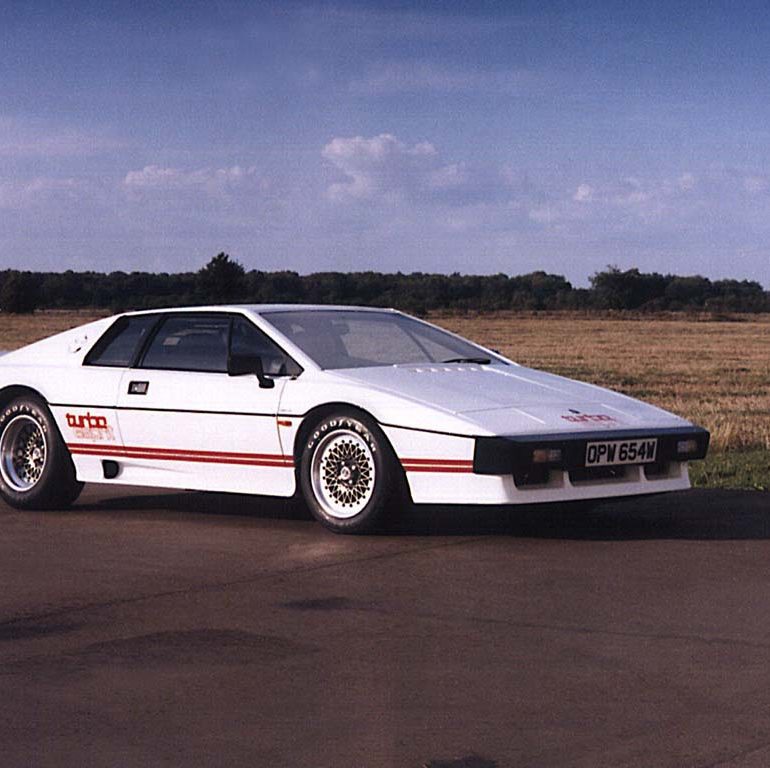

1980 Lotus Esprit Turbo

Years: 1981-1986

Names: Turbo Esprit / Type 82

Units: 1,845 (2,274 including HC)

Engine: 2,174 cc inline 4 turbo

Power: 210 bhp @ 6,250 rpm

Torque: 200 lb/ft @ 4,500 rpm

0-60 mph: 5.6 seconds

April 1981 to October 1986. Cheaper ‘production’ version, with reduced trim spec; except for earliest models, all have wet-sump lubrication, BBS wheels. Higher compression ratios for the engines was indicated by the ‘HC’ moniker. Turbo shared common chassis and body with S3.

Cheaper ‘production’ version, with reduced trim spec; except for earliest models, all have wet-sump lubrication, BBS wheels. Higher compression ratios for the engines was indicated by the ‘HC’ moniker. Turbo shared common chassis and body with S3.

Highlighting this Esprit is a Garrett T3 turbocharger. After 1986, when production of this car stopped, every Esprit thereafter had forced induction. Essentially, the Turbo Esprit was an entirely new car. The chassis of which was of S3 type, that followed the Turbo in 1981.

The Turbo Esprit retained the aerodynamic body kit of the Essex cars and featured prominent ‘turbo esprit’ decals on the nose and sides.

Though the car still carries the Esprit tag, the 1980 Turbo Esprit is effectively a new car, where the 16-valve engine has been punched out to 2174cc, using a bore of 95.25mm and a stroke of 76.20mm. The four-cylinder aluminium engine provides a manufacturer’s claimed 210bhp at 6250 rpm and 200 lb ft of torque at 4500rpm. A Garrett T3 turbocharger which is mounted downstream of the twin Dellorto carburettor supplies boost up to 8lb p.s.i. and the engine operates on a 7.5:1 compression ratio. The turbocharger lubrication is direct from the main oil gallery, with drain to the dry sump (which later changed to a wet sump).

Related: Esprit Ultimate Guide / Current Lineup / Lotus Models / Lotus News

The current Esprit 5-speed gearbox has been retained and is attached to the engine block by a new alloy bell housing, while power is transmitted via a new clutch with increased capacity to the wheels via plunging constant velocity joint driveshaft.

The Turbo Esprit’s backbone chassis is completely new — zinc galvanised and with a five year guarantee subject to normally use — incorporating a wider front box section and suspension mounting points. A new space frame engine and transmission section is included, giving a four point wide-based mounting system and increased torsional stiffness. The front of the chassis houses a new full-width radiator and oil cooler with increased capacity.

The new front suspension has been adopted from the Elite, with the track increased by an inch, while the rear suspension is also revised, with unequal length transverse links with radius arms.

Bodyshell changes include large wrap-around front and rear bumpers, a full-width front spoiler for better air flow to the larger radiator/oil cooler and improved aerodynamics and a redesigned tailgate area to provide direct cooling airflow. NACA ducts have been moulded into the sills to provide cooling air into the engine compartment.

Cockpit changes have been made, including an instrument panel which now boasts a turbo boost gauge and speedometer running up to 170mph. Air conditioning controls are now situated in a centre console panel and all switchgear is backlit when main and side lights are illuminated. The seats have revised foam foundations and with new head restraints.

Pictures

Specs & Performance

| submitted by | Richard Owen |

| engine | Type 910 Inline-4 |

| position | Mid Longitudinal |

| valvetrain | DOHC, 4 Valves per Cyl |

| displacement | 2174 cc / 132.7 in³ |

| bore | 95.2 mm / 3.75 in |

| stroke | 76.2 mm / 3.0 in |

| compression | 7.5:1 |

| power | 156.6 kw / 210 bhp @ 6250 rpm |

| specific output | 96.6 bhp per litre |

| bhp/weight | 182.93 bhp per tonne |

| torque | 271.16 nm / 200.0 ft lbs @ 4500 rpm |

| body / frame | Glass Fibre Reinforced Plastic over Steel Backbone |

| front tires | 195/60 VR15 |

| rear tires | 235/60 VR15 |

| front brakes | Discs |

| f brake size | x 267 mm / x 10.5 in |

| rear brakes | Inboard Discs |

| r brake size | x 246 mm / x 9.7 in |

| front wheels | F 38.1 x 17.8 cm / 15.0 x 7.0 in |

| rear wheels | R 38.1 x 20.3 cm / 15.0 x 8.0 in |

| steering | Rack & Pinion |

| f suspension | Upper Wishbone w/Lower Transverse Link, Coil Springs, Anti-Roll Bar |

| r suspension | Double Transverse Links w/Radius Arms, Coil Springs, |

| curb weight | 1148 kg / 2531 lbs |

| transmission | 5-Speed Manual |

| gear ratios | :1 |

| top speed | ~241.4 kph / 150.0 mph |

| 0 – 60 mph | ~5.6 seconds |

| 0 – 100 mph | ~14.6 seconds |

Lotus Esprit Turbo Prices

1989 Lotus Esprit Turbo SE – did not sell for $28,000. All original with only 8,000 original miles. Pristine condition always kept in climate controlled storage for past 17 years. Powered by turbocharged 4 cyl with 5-speed. Removable roof panel. Air conditioned. Built in radar detector. Original spare tire and tool kit. Original owners manuals with dealer brochure. Copy of window sticker and sales documents. This may be the lowest mileage of all original 1989 Lotus Esprit in existence. Auction Source: 2011 Monterey Daytime Auction by Mecum

Lotus Esprit Turbo Review

Alternative Cars May 1983 – What They Said

by John P E Maitland

Emotive Esprit

It took the meeting of two great men to create a supercar…

The place; Geneva’s Auto Salon. The date; 1972.

The men; Giorgetto Giugiaro and Colin Chapman. The Car; Lotus Esprit.

At that moment began a chain of events which led to the birth of a car which is arguably the best car ever built in Britain. But they didn’t know it at the time. . . The initial idea was that Giugiaro’s Ital Design company should build a one-off special to fit a slightly stretched Lotus Europa chassis and indeed it was just such a prototype that made an appearance at the Turin exhibition in the same year. But though the name Esprit dates back to then, it was not until 1975 that the first production Esprit was shown to the public.

Changes in those three years had been many, and the modifications which have since followed even more extensive. But the most exciting of all was the introduction in 1980 of a turbocharged version of the Esprit S2 with an updated bodywork design by Giugiaro. And with the April 1981 release of the further improved S3 Lotus Turbo Esprit, who could now doubt that the coming together of two great men had produced a true ‘Supercar’. . .

But impressive though they are, specifications tell only half the story. . . We describe the various emotions the Esprit provokes.

In everyone’s life there are certain goals to be achieved. Some people want to climb mountains, others like to cannonball over Niagara in barrels – I like to drive fast cars. No doubt the Psychologists would say this is the result of repressed subconscious adolescent urges. And no doubt this is true . . . But when the opportunity came to test drive the Lotus Turbo Esprit, the adrenalin began to pump with renewed vigour as one of my long cherished ambitions was about to be realised.

The moment I climbed into the cockpit, a number of conflicting impressions hit me simultaneously. The interior was substantially cosier than expected, particularly for a car with fairly generous exterior dimensions, and was a decidedly snug fit even for a chap of my modest stature (5’7″). However, it still somehow felt right. Gazing out through the mammoth expanse of glass, visibility was surprisingly good (the bonnet was predictably invisible) and all-round vision was more than adequate. Even more encouragingly, the dials were easy to read, all the controls fell naturally to hand and the laid-back seating position was both comfortable and in keeping with the kind of image that we all, I suspect, secretly aspire to. Familiarity bred confidence in a machine which rapidly felt like an extension of the driver. An impression heightened by the ‘shoehorned into the seat’ feeling and the all-enveloping black trim. The car looked mean and purposeful, both inside and out. Colin Chapman, God rest his soul, had yet again delivered the goods – with a little help from Giugiaro of course. The Elan had been good, but this promised to be something extra special.

I wasn’t to be disappointed. The engine barked into life at the first turn of the key and displayed none of the temperamental histrionics associated with some of the more cammy foreign competition. Pulling away from rest, the revs rose with a rapidity and smoothness that belied the engine’s humble four pot specification. Lotus had certainly done their homework. Turbo lag was minimal and power delivery between 2500rpm and 4000rpm was perfectly progressive, after which it really pulled out all the stops. This suggests that Lotus have gone for a combination of Turbo boost and tweaky cams to wring extra performance from the 910. But this all adds to the fun, for the engine is a gusty, hard working, unit that never complained once, whether idling in traffic or cruising at well over the legal limit. The only thing that detracted from otherwise dazzling performance was a somewhat heavy and agricultural gearchange that precluded one from zipping through the ratios with quite the rapidity that one would have liked.

However, in practice, the Esprit was still very quick by anyone’s standards. Bend which used to be taken at 50mph on the limit, now became 75mph exercises in ‘cornering on rails.’ And overtaking involved nothing more than a mere blip of the throttle rather than the more usual frantic effort to avoid oncoming traffic. At all time the impeccable handling gave one the confidence to revel in the power and speed. Undoubtedly this is a car designed to be driven hard, beyond the normal limits ( . . . normal that is for normal cars) of driving prudence. And herein lies its Achilles heel. At ‘normal’ speeds (e.g. within the speed limits!), the tyre and suspension tuning can conspire to produce a car which is a bit of a handful. The NCT 60’s with their rigid side walls exhibited an unsettling tendency to follow the white lines and bumps in the road, and in traffic the steering became uncomfortably heavy.

However, on the open road, the Esprit was exhilarating and a joy to drive. High speed stability was remarkable, even at nearly twice the legal limit, and made for extremely soothing cruising. The expanse of the frontal glass, the sheer width of the cabin and the harmonious drone from the power plant gave one a paradoxical feeling of spacious coziness. And it’s probably the closest one could feel to piloting an aircraft whilst still remaining on the ground. In the true Lotus tradition, the car handles and goes every bit as well as it looks. On the road it’s a real head-turner and commands a reverential respect from other road users that few other cars can aspire to. In short, its a real supercar with few other peers. It has its faults, but then a flawed masterpiece is still a masterpiece nonetheless.

by John J Laitland

Motoring journalists, as a breed, tend to become rather blasé about vehicles they test. They step into cars not with any particular sense of anticipation, but rather with a metal checklist of potential faults and duly record their views on such minutiae as the heater controls, the number of seat position permutations and the effectiveness of the rear window heater. It it, after all, a job like any other, and one can forgive the tendency for traditional assessments to be rather ‘dry’ and humdrum.

But when I was handed the key to the glowing red Lotus Turbo Esprit it was hard to contain my excitement, for by any standards the Esprit is something really rather special. With a 0-60 time bettered only by Aston Martin’s £45,000 Vantage and a top speed of more than double the national limit the Lotus flagship is every inch a supercar – I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it!

Settling into the luxurious, leather-trimmed cockpit I was immediately struck by the self-indulgence of owning such a purposeful beast. A passenger, after all, would soon tire of the lack of head and legroom. A wife would point to the lack of luggage carrying capacity. A cynic would scoff that there was nowhere one could use the car’s performance to the full. But as I was soon to discover, none of that matters at all!

The first few miles in the Esprit were gentle ones. After all, in a car with an £18,000 plus price tag (not to mention a 0-60 time of 5.6 seconds!) one doesn’t want to make mistakes . . . And yet, as I quickly learned, the Esprit is no more difficult to drive than any other. Indeed, with its slick gearchange, light foot controls and beautifully responsive steering it was, if anything, easier. Okay, so there’s not a lot of rear vision, but then again, not a lot of cars are quick enough to be capable of trying to overtake you. . .

It would be easy to ramble on about how quick it is possible to drive an Esprit. Suffice to say though that its capabilities are far higher than mine. Given a mere whiff of the accelerator the Esprit simply surges – on and on, faster and faster, as if it knows no limits. It isn’t just straight-line performance either – any powerful car with reasonable aerodynamics can devour a straight. But the Esprit not only copes with corners as well, it enjoys them! No doubt it is possible to press still harder and turn the slight understeer into oversteer if one tried hard enough, but it would take some doing – and a braver drive than I!

Of course I loved the visual impact that the Esprit makes wherever it is seen _ the glares of pure, unadulterated envy and undisguised admiration. And of course I loved the slightly awed requests from friends simply to be allowed to sit behind the Lotus’ wheel. And of course I loved the amazement on the face of the Rover-driving gent in the petrol station who looked in total disbelief to see one so young (not to say scruffy!) in such a desirable machine.

But above all I adored the sensation of driving a car whose limits were so much greater than my capabilities. Everything I demanded of the Esprit it performed with contemptuous ease, as if to ask, ‘Can’t you think of anything more difficult than that?’ It tore past streams of cars where one could normally only pass one or two. It flew through corners with breathtaking ease. It stopped quickly and securely enough to prevent me looking stupid (or worse!). It whistled up to speeds which made ‘quick’ cars seem like milk floats by comparison. And it did all this, and more, without any sign that to do such was extreme in any way . . . Freed from the constraints of boundaries over which no man dare to tread I felt as if I was in a dream. Nothing I could ask would be too much for the Esprit. Truly I felt like I was ‘King of the road’.

Inevitably, handing back the keys of the Lotus after all-too-brief an acquaintance was a bitter-sweet moment. For it signified a return to the reality of cars which know extremes – cars that might have looks which approach the beauty of the Esprit, or even better them, but cannot match its astounding capabilities. But it was a moment to treasure too, because for a brief second I felt that if I were to never drive again, I would still die a happy man . . .

by David Sumner Smith

The keys which had been so fervently withheld for the previous five days were finally handed over. My months of drudgery as the sole skeleton on the all-demanding Kit Car magazine had come to fruition with my opportunity to drive one of the most dynamic of production supercars – the Lotus Turbo Esprit.

As I stepped out into the crisp February air, the toil having taken its toll on the journalistic circuit banks, the gleaming, almost glowing red wedge seemed to exclude a surreal aura, the perfection of its surfaces heightening its improbability as a man-made machine.

Ever the gentleman, I beckoned darling Alison to the passenger door, but curses! A couple of ad lib off-the-cuffs were required to maintain the cool image as I fumbled to find the correct key from the four on the ring. Another from the remaining three opened the spitfire-type lock on the rear hatch, but alas, the Lotus was obviously designed for the person who carries a document rather than an executive case. Subsequent failure to open the front had dear old Al’ carrying both brief case and editorial flying jacket on her lap. A couple of cranks saw the blown twin-cam roar into life, but the archaic and poorly lit smiths instruments, and the out of step rise of the headlights typified the Italian-styled exotic as a British car. However, no sooner did the Garrett T3 blower come in to squirt the Esprit to sixty in a whisker under six seconds, than these petty niggles were simultaneously blown away. The aircraft-nose exterior and interior styling is wholly unpretentious and a worthy compliment to the soaring, surging qualities of the Esprit.

The revelatory experience of driving the Lotus is such that it takes but a couple of miles to settle comfortably in the sumptuous leather of the cockpit, and to begin concentrating on the serous business of driving the car. A poke in the eye for the self-made critics who snort ‘I could never drive anything like that’. The Esprit Turbo is easy to drive, and easy to drive well – not in a self-gratificatory sense but in a rewarding way. The precision of the response from any driver input provides instant, directly proportional feedback with a wide margin of safety – you can hardly put a foot wrong. A stab at the throttle and the turbo propels the car forward at lighting pace, a tug at the wheel and it goes sweetly round your chosen line, a prod at the central pedal and it’s as if your own hands were pulling the discs up squarely. And all the time the body of the car bobs gently up and own while the compliant but taut suspension keeps the wheels in contact and the occupants in one piece, in what is truly a wonderful ride.

Few cars demonstrate such tremendous ability to satiate the driver, so magnificent is the Lotus chassis. Despite the superlative feed-back gained through the controls, the car is far less demanding than a glance at the data sheet might suggest, its slot-car cornering power and subsequent acceleration to incredible speeds putting one seemingly in control of one’s destiny.

Only through first hand experience can one begin to appreciate the qualities of the genius who saw non barriers in the development of this car. No barriers to the wring of over two hundred and twenty smooth and tractable horses from four cylinders. No barriers to isolating the necessarily large wheels which transfer the power, nor the conferring the solidity of a two-ton Jaguar on a car with half the mass. The Lotus Turbo Esprit is quite simply the ultimate driving experience.

by Sandor Ballago

Car Road test, November 1981 – What They Said

Roger was driving as we forged into Teesdale. ‘ What a road!’ he said with delight as we cleared Middleton and saw the tarmacadam snaking for miles ahead along the dale’s northern edge, picking its way between the moors rambling imperiously to our right and the valley tumbling moodily below. The trucks and most of the other cars had chosen easier, more obvious roads. We had to share the peace and pleasure of this one only with a handful of local farmers shuffling along in Land Rovers and a few nomadic sheep. The sun was dropping, making the sheep and the guideposts and the lines on the road show Persil-white against the moors’ vivid colours, but it was off to our left and wouldn’t be in our eyes. Perfect. I reached up the turned off the radio.

The 250 miles from London had given Roger time to settle into the Lotus, time to get an idea of tis smooth power, crisp response and refined behaviour. He was now about to learn of its exceptional speed, its unerring precision, its remarkable grip, its immense stability and lovely cornering balance. He was about to discover the depth of the Turbo Esprit’s ability and why, at a stroke, it has lifted Lotus to the highest plateau of sports car performance.

Earlier sessions with Turbo Esprits had endowed me with that balmy knowledge and, as Roger began to wind the Turbo out in the gears, I nestled back into my snug leather lounge with a private smile, confident that the car would do nothing nasty to its driver and ready to enjoy the experience of watching him reach deep into it in order to sound its depths.

The Lotus began to devour the road. Most of the bends soon proved to be too slow for second, however tight they might have looked. Third was the right gear. Its flexibility, mid-range oomph and 91 mph at 7000 rpm give it precisely the right spectrum. It contained its own message too: the Turbo is very fast but is not demandingly fast. Its power is not peaky; it does not lie within a narrow rev range. You do not have to keep flicking away at the gear lever. The engine might be a 2.2 litre four but it delivers its performance with the magnitude of a V8. Thus third is a superb gear for a series of bends, strung close together. You could come out of a tight bend as slowly as 30 mph and still have instantaneous acceleration, or charge through a faster bend at upwards of 80mph and still have plenty of revs and power in hand to provide for a full-power exit. Third in the Turbo Esprit, gives you so much while demanding so little, and you’ll use it to attune yourself to the car until you’ve gained adequate knowledge of its balance, become accustomed to the entry speeds of which it is capable, and its accelerative power within the bends, to allow correct use of second for the slower bends and fourth for the faster curvers. You will want to do it correctly, to choose the right gear, to select it at the right point on the road, to use the right amount of power not because the Turbo insists but because you’ve become so quickly aware of the fundamental smoothness and fussiness with which it cruises, bends or not. You will wish to match its smoothness – as if you were a supremely accurate guidance system… simply because it deserves to be handled like that.

‘Brake hard and deep into a bend and the Turbo Esprit budged not a whisker at either end’

Roger pressed on, the gearshift starting to work. Occasionally, I tensed as we stormed towards yet another bend, particularly the right handers where there was nothing ahead but the remnants of a skimpy fence and open air. Surely the car was going too fast to get around? Yet Roger was accelerating, not braking, I’d remind myself that it was my impression that was wrong, not his.

So my anxieties were fleeting, infrequent things, diminishing with each mile as I learned my own lessons. I switched to analysing my own environment. We were pushing hard and fast through bends tight enough to cause the car to generate a great deal of lateral force, yet I was still lounging comfortably in my red leather tub, bounded on one side by the soft padding of the door trim and on the other by the leather over the deep central tunnel, and held firmly in place by the seat’s soft, deep side sections. I felt the lateral forces but was largely unaffected by them because the car corned so flatly. It was equally free of fore and aft pitch, maintaining a beautifully flat attitude whether braking or accelerating, rising over crests or dropping into dips Bumps affected each wheel at a time, not the car as a whole, and then only very little.

The suspension, while maintaining such marvellous directional and lateral stability, worked with enough flexibility to absorb the bumps without disturbing my comfort. Yet there was enough communication to give me reassurance too. I marvelled. I was being transported as stably, levelly and comfortably as if we were still on the motorway. As a car for a passenger, the Esprit had already displayed ample virtue.

Roger was driving masterfully but, comfortable as a passenger or not, I could stand it no more by the time we’d covered the 25 miles to the township of Alston and there wasn’t much left of the dale and its exquisite road: I had to have the pleasure of driving the Esprit there myself. Even as we entered Alston I was selfish enough to as Roger if he’d mind swapping over.

Experience said cool it, settle in slowly. Establish an equilibrium. Play yourself into the car, and the car into the road. Don’t make the fatal mistake of going too fast too soon. Familiarity mercifully shortened the normally lengthy process of adapting to the Esprit’s high steering wheel and scuttle, its intimidating 6ft 1in width and its low driving position. Given that, the car felt instantly and beautifully available. I wasn’t so fussed about the gearshift mounted high on the central tunnel as Roger had been; the point lay more in the short-throw delicacy of the mechanism itself, although changes into second had to be slower because of slightly dodgy synchromesh in our much-abused demonstrator than was normal. If the narrowness of the footwell was annoying, I was pleased enough again to accept the trade-off of precise, short-action and well-balanced pedals, set deliberately so that their efforts are match as closely as possible to each other and to the gearshift and steering.

As we ambled through what was left of Alston, I mused that in the Turbo Esprit the 195/60VR15 Goodyear NCT radials on the front wheels took the weight of the steering slightly beyond the normally impeccably complete Lotus balance. But that it had its own compensation too: there was the meaty feel of the small, thick-rimmed leather-covered wheel to match the reassuring feel of the steering itself. And, dribbling through Alston’s narrow streets, I was pleased to have the Esprit’s fine part-throttle response and its outstanding flexibility. Here was a docile car happy to be driven at walking speed in any congested street yet, in a few minutes, it would be travelling so tremendously quickly.

‘Then it was back on the power to feel the car balance out as it left the bend behind’

On the open road again, a start a what seemed like 50mph was soon shown by the accurate speedo really to be much more. The car felt so secure. I concentrated on my gearshift points. At 7000 rpm (with another 300prm to go before encountering the ignition cut-out), first was going to give me 41mph, second 62, third its lovely 91 and fourth a handy 123. Fifth, I knew, would take the Turbo to a certain 152mph and, given a lot of room, maybe a little more. On this road fourth was more than enough, although such is the Turbo Esprit’s torque – with its curve running flat enough to spread its peak of 220 lb/ft all the way from 4000 to 4500 rpm – that fifth would provide plenty of solid performance upwards of 60mph or so too. The choice of tempo was all mine.

The stability of the Esprit was again one of the first things that stood out as I began to tackle the bends, mostly more open on this stretch of the road than they’d been the other side of Alston. There was such an overwhelming feeling of security, creating the impression that, without a trace of flab in the suspension or in the transition from one modest attitude to another, the car would always retain its unerring precision. That impression was reinforced by the response to the steering. Turn the car into a bend and it just followed the line precisely; tighten it even more to hug a bank within a blind corner and it did that perfectly too.

Brake hard and deep into a bend and it budged not a whisker at either end. Give it full power on the way out and the tail refused to move unless the bend was slow enough for first, or happened to contain a bump of two at the point where the full 210bhp was being unleashed. Even then a snip of opposite lock – nothing more than a tiny flick of the wrists – or a reduction in the power for a split-second had it perfectly back in line. The rear end grip was staggering. But even more surprising, even more pleasing in a curious way, wass the absence of anything that might be called appreciable understeer. Pushing as hard as is possible with the Turbo Esprit into bends should sometimes bring enough understeer to force you to back off or face running very wide at the front. Within all reasonable (but remarkable) bounds, it just wasn’t happening in the Lotus. So with a feeling of security and trust in the car that built on my earlier experience to become the greatest I’ve ever gained from a car, I carried on with the pure pleasure of making mincemeat of that road. ‘What a car!’ said Roger with awe as we left Teeside behind and headed on along more open roads for Gretna and Scotland.

It was the pursuit of pleasure that lay behind our journey anyway. My plan to give away a Turbo Esprit to a CAR reader was coming to fruition, and if I couldn’t keep it myself then I was jolly well going to grab one for a few days and set out on a trip that would arm me with a private bank of memories. I wanted sheer indulgence and I knew of the roads upon which I could get it. If I needed any excuse at all to head for them, well then I wanted a new arm and cartridge for my turntable and why not take it to the Linn Sondek factory in Glasgow than have them fitted at a dealer in London? Art Director Stinson and photographer Dawson played into my hands by having to go to the Highlands to photograph the Range Rover and Mercedes-Benz Gelandewagen. Meet me, I said with a wicked smile, at the top of Rest And Be Thankful, in the hills above Loch Fyne. Roger Cook, when he heard of my plan, found reason to leave his Radio Four Checkpoint programme for three days ‘research’ in Scotland.

We carved across the A74, the obvious route north to Glasgow, at Gretna and headed further west for Dumfries. Then, as we ran up on long rows of articulated lorries that were themselves being held up by doddering cars, another aspect of the Turbo Esprit came into play: its straightline performance. We could hang back slightly, spot a gap ‘way up ahead and then steam past with room to spare, and it didn’t seem to matter how short the straight. If we were down to 40mph, full throttle in second gear had us a 60mph in just over 2 sec. That sort of overtaking prowess brings a combination of safety and exhilaration that creates a feeling of wonderful relentlessness.

We had enough performance to deal with anything we encountered on the final stage of our run into that troubled, passionate Scots city – and soon we encountered little more that the odd truck and a few cars, all despatched as if they were motoring in a different time zone. Our relationship with them seemed surreal. Darkness had closed in. The Turbo’s lights were up to the job and we cruised even faster than I had anticipated. It was in the bends that were long and blind that it was perhaps most impressive of all. Once it had been settled with throttle lift-off, turned in and then fully stabilised with the mildest possible re-application of throttle so that it felt as if it were being restrained by a gigantic soft-gloved hand, it just followed the curve so very perfectly, brushing the grass with extreme precision in the left-handers and following the road’s white line in the right-handers. That feeling of perfect control and stability when you’re in a long and blind bend, and you must hand in equilibrium between a trailing throttle and serious power application, is crucial – perhaps the ultimate pointer to a sports car’s quality. The Lotus was better than flawless. capping its in-bend balancing act with its delightful, potent surging out of the bends – tossing them behind it – when the exits were at last in sight and the throttle could be pushed fully open. Superb, too, was the way in Which I could bring it blasting out of a demanding right-hander to be faced just a few yards later with a left. More often than not there was no need to brake before turning in. When it was necessary, the Lotus slunk squarely into the road with the pedal delivering feel by the millimetre and millisecond. Again the Lotus stayed perfectly on line and resisted any tendency for the nose to run wide. The remarkable thing was that while it came so perfectly accurately into bends, it maintained such stability that it never twitched in too far with the tail edging out. You could play, to see if there was fault, by really standing on the brakes. Still the car maintained perfect attitude. It was so incredibly safe as well as so outstandingly pleasurable to drive, and the effort I needed to exert to cover the ground so swiftly on a challenging road was satisfyingly low. Happily, there was great comfort with it all too. The Turbo’s suspension works as quietly as it does competently. Roger, I noted, was asleep long before we neared Kilmarnock and swung properly north onto the A77 for Glasgow. I’ve had some fine drives to Glasgow, but this one had been the best and I was as fresh as I was happy as we drew up at last at the house of the good Ivor Tiefenbrun, engineer, turntable maker par excellence and lover of fast cars. ‘Is it as good as it looks’, he asked as we settled down to attack his supply of 43 year-old Macallan, and all Roger and I could do was look at each other and grin like a pair of Cheshire cats.

It was raining next morning as we worked our way along Loch Lomond side to the soaring hills and great swooping glens of the south-western highlands. Not even the Turbo’s prowess could take us beyond the clutches of mimsers huddling nose-to-tail. We just kept our distance and relaxed with the warm feeling of comfort and security that the Lotus imparted. But we broke loose on the long, open, glorious run up through Glen Croe to the Rest And Be Thankful summit. The Lotus sprinted up the long climb like a racehorse turned loose on downland. I’d dreamed of charging this superb piece of road with a properly fast car; the Lotus brought it all to fulfilment. There, at the top, were Messrs Stinson and Dawson. Just into our stride, we had to stop. For the rest of the day we were mainly puddling about finding locations and taking pictures, but there were dashes in between, certain bends to be taken flat out again and again. The pottering even had its use: it threw up the exceptional flexibility of the Turbo’s engine; the way it would pick up so smoothly and unhesitatingly from as little as 1500 rpm in second, third or even fourth. In fifth, it was responsive enough to provide notable pace from around 2000 rpm.

Serious acceleration started from around 2500 rpm and beyond that it was dynamite. Yet there was no peakiness, none of the big step that is characteristic of turbocharged engines; it was only the curious twitter of the wastegate dumping excess pressure when the throttle was released at high revs that reminded me that the engine was turbocharged at all.

The only difficulty in handling the car on narrow roads – or in the city – stemmed from its vision. Most mid-engined cars are poor in this area; the Esprit, with its striking styling, is among the worst with the Turbo further handicapped by the louvres our the engine. They restrict rear vision even more. Turning in tight areas or parking thus required careful checking of the electrically-adjustable mirrors and a lot of neck-craning. The steering, however, was never nastily heavy and nor was the clutch. So, through a long day spent trundling about on all sorts of tiny roads, in and out of villages, on and off precarious piers, Roger and I lived easily with the Turbo and we’d dearly have loved to have turned south down the western side of Loch Fyne and pursued the A83 all the way to Campbelltown and its Springbank, taking the opportunity to stay at that haven for gourmets and CAR readers, the West Loch Tarbert Hotel, on the way. But we had to head back to Glasgow, although even then we had further cause to admire the Turbo because, to avoid the congestion along Loch Lomond side we took the alternative road from Arrochar to Helensburgh, and found that the Lotus handled its endless stream of dips and crests with exceptional aplomb. It crested the sharp rises flatly and securely and never once bottomed in the dips. On a road that would have had many cars with a lot of road clearance and long suspension travel trundling sedately, we travelled unabated. I took the reserved and cynical Ivor out for a swift blast in the car that night, the roads almost awash from a downpour, and hoped that the pace seemed as effortless to him in such atrocious conditions as it did to me; by then I knew so much about the car’s ability that I was afraid of over-selling it.

We went down to his factory the next morning, ostensibly to pick up my newly-updated turntable but to look too. To wander within the Linn factory is very much like being within the engine shop at Ferrari – or Lotus. There’s the same fine engineering, the same sort of dedicated people making and assembling components with exceptional efficiency, patience and care. The concept of the Linn turntable is quite straightforward but all its components are machined to within 0.001in, thus making it an object of marvellous precision and helping towards its remarkable performance. In the fight against low-quality, digital recording systems, Linn are also building their own direct-cut recording equipment. The place was humming, a pocket of outstanding British achievement, like Lotus themselves.

‘The Lotus slunk squarely into the road with the pedal delivering feel by the millimetre’

We took the A74 south towards the borders but swung off again at Gretna to retrace our steps; we weren’t about to bypass that marvellous road through Alston. There, we changed drivers once more so that we each from the sections we’d missed on the way up. Again there was very little traffic and I pushed the Turbo really hard. There were enough bumps in some of the bends to make my wrists ache as I pressed the car in as fast as visibility allowed; still the Lotus refused to run wide at the nose, or to be moved off line by bump steer. It just went where I directed it, with the wheel jiggling solidly in my hands as the wheels rode over the irregularities. I used all the road and ran the car flat – flat in every appropriate gear and braking as hard and late as I could. It was glorious, a new high in 15 years of high-performance motoring, and with its own climax. I came over one crest to find the road spearing down to a visually open right hander that ran through 90 deg left. I kept the Lotus flat and swung it really hard into the bend, harder than I’ve dared swing any car into a road bend before, and entrusted myself solidly to the roadholding. The tyres loaded to the limit – 1.1g, Lotus claim – but the Esprit simply went around with just the mildest trace of understeer (felt as a slight lightening at the wheel) and then a nudge towards something approaching, but not quite, oversteer as the tail was pushing hard down by the full power of maximum revs in third. The g-force was high but there was still time for the mind to record the car’s flatness. The following left-hander was of smaller radius and I had to brake hard for it and take second gear with a swift double-shuffle to compensate for its defective synchromesh. Then it was back on the power again to feel the car balance out as it left the bend behind in another fraction of a second and romped onwards. I’d never been around a couple of tight corners so quickly and nor had Roger. We grinned at each other and passed on for London, content now just to cruise quite sedately.

When we filled the car we found that we’d returned 20.8mpg after all our hard charging – little less than the 21.3 we’d obtained on the way north. Even with all our stopping and starting in Scotland we’d bettered 20mpg. Later, when I filled the car in London after covering the final part of the return trip on the A1M and M1 at a brisk cruise, the figure was 26.1mpg. Set against the Turbo’s performance and cross-country pace, the figures were incredibly good.

When we’d been driving the Turbo swiftly and using all the gears and the performance, we hadn’t noticed noise. On the motorway, we were conscious of a fairly high but not objectionable level of sound from the fat tyres and wind noise that increased significantly with speed. If you were to be travelling beyond 120 mph across Europe you wouldn’t have much chance to listen to the radio, though the Turbo still stands as commendable refined overall. The ceiling console installation of the National Panasonic stereo system was far too fiddly for practical use and, ridiculously, the radio was FM only. We forgot the thing altogether and gave it up as an unfortunate £600 joke with no place in a car as valid as the Esprit.

Luckily, it was merely an option. There was also a mysterious fault with the air conditioning in our car. For part fo the journey it failed to work at all, a handicap in the Esprit because the cabin grew uncomfortable in warm or muggy conditions. We could have done with more luggage space too. We managed to wiggle the turntable’s box into the boot proper but it wasn’t easy. Only one small bag could then go in too and the other had to be squashed around the spare wheel in the Esprit’s nose. We found ourselves wishing Lotus could improve the luggage capacity. It would also have been nice to have had aesthetic temptation beneath the engine cover. Its own securing lugs, the oil filler cap and the plumbing looked cheap and messy thereby failing the real engineering which is of the very highest design and developmental quality. I had been happy to tell the people at Linn about the car; I didn’t really want to show them its innards.

But, dear me, our long and happy excursion had left neither Roger, the perfectionist, nor me, the cynic, in any doubt about the Turbo Esprit’s road-going brilliance. It transported us and inspired us, it confirmed my view of its desirability and satisfied my whim. One of you will soon own a Turbo Esprit. I’ll swallow my avarice; I’ll have my memories.