1976-1980 Lotus Esprit S1

Years: 1975-1978

Names: Series 1 / S1 / Type 79

Units: 718

Engine: 1973 cc inline 4

Power: 160 bhp @ 6,200 rpm

Torque: 140 lb/ft @ 4,900 rpm

0-60 mph: 8.4 secs

The first Esprit had a Type 907 inline-4 which produced 160 bhp in European markets and 140 bhp in America. The engine was supported by a steel chassis and covered in a sleek fiberglass body. Despite modest power, the styling and handling of the car kept it selling.

With the Esprit, Lotus entered the modern supercar market for the first time. It’s exotic shape was good enough to extend production from 1976 all the way to 2004.

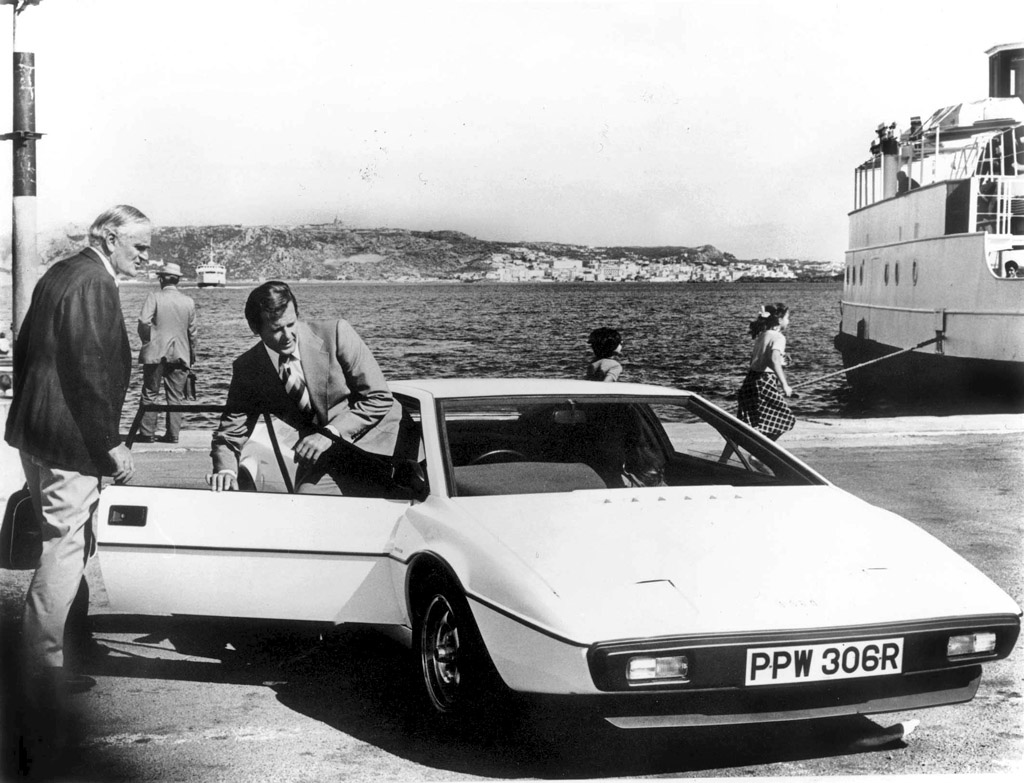

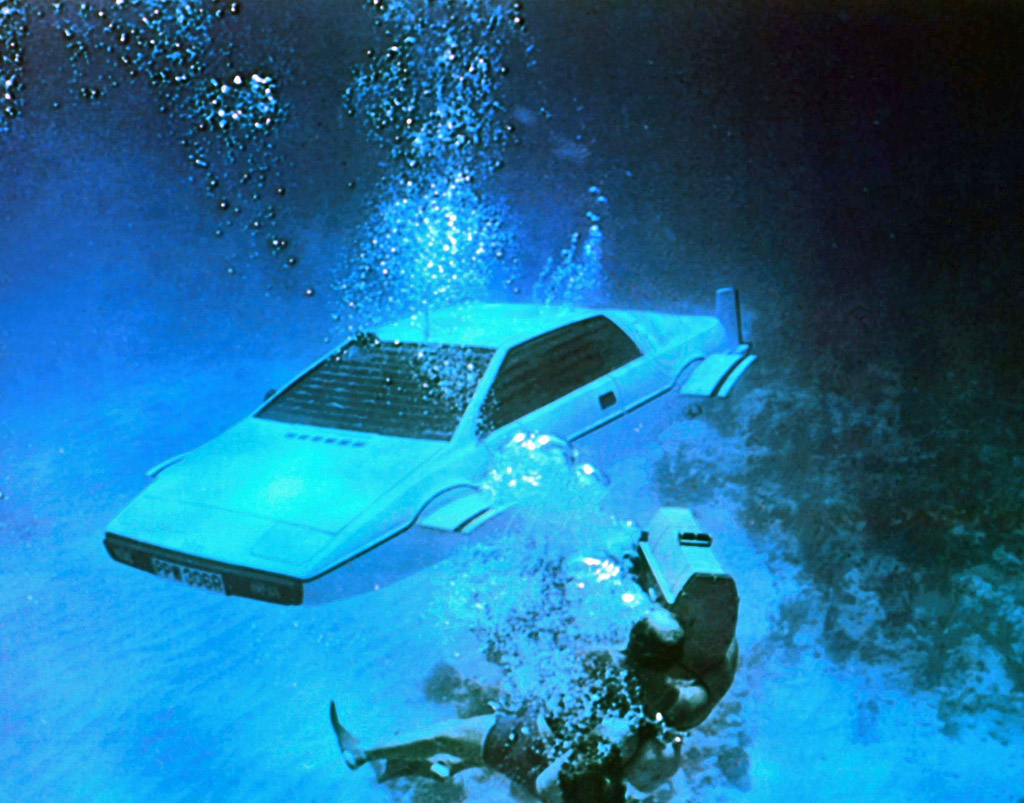

Featured in the 1977 James Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me, Roger Moore showcased the Esprit’s performance by eluding a chasing helicopter. Unlike the Astons of Bond’s past, the Lotus transformed into a submarine and jumped into the sea.

The Esprit story started much earlier when Giorgetto Giugiaro debuted the ItalDesign M70 concept at the 1972 Turin Motor Show. This car’s ‘folded paper’ front end was radical, yet production worthy. Four years later,a production version debuted at the 1975 Paris Motor Show.

At the center of the new Esprit was a Type 907 inline-4 which produced 160 bhp in European markets and 140 bhp in America. This was mounted at 45 degrees in relation to the chassis to keep a low center of gravity. The engine was supported by a steel chassis and covered in a sleek fiberglass body.

Despite modest power of its initial specification, the styling and handling of the car kept it selling. By 1980, the Esprit was upgraded Series Two specification including a new front spoiler and rear valance.

Related: Esprit Ultimate Guide / Current Lineup / Lotus Models / Lotus News

The Spy Who Loved Me Lotus

A white 1976 Lotus Esprit from the 1977 film The Spy Who Loved Me, starring Roger Moore and Barbara Bach, was sold by Bonham’s auctioneers on 1 December at its annual motoring Auction Sale at Olympia, in West London. The car fetched £111,500 GBP.

This Lotus Esprit is one of two complete, fully functioning cars that were used for the driving scenes in the motion picture ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’, starring Roger Moore as secret agent James Bond, ‘007’. Approximately nine Esprits were used in different guises, but bar these two the rest were shells, some of which were used in filming the Esprit’s transformation into a submersible.

After the movie’s completion, the car was despatched Lotus and put back on the production line to be returned to standard trim and sold on. The mounting for the clock was removed, the seats and headrests returned to standard, the engine serviced and a black Lotus badge put on. This ex-Bond Esprit later passed into German ownership, its last long-term owner in that country carrying out a mechanical restoration.

Styling

The styling of the new car, if not its engineering, began in 1971 following a chance meeting between Giorgetto Giugiaro and Colin Chapman at a motor show. Even in the early Seventies, Giugiaro had a formidable reputation as a stylist/designer, having started his career at Fiat, before moving on to Bertone, then Ghia, prior to setting up his own business, Ital Design, in 1968. Chapman knew all about Ital Design, and everyone knew about Lotus, so there was never any lack of understanding between the two. Quite simply, it seems, Giugiaro wanted to know if he could work up a special body style on a Lotus, and Chapman, with the M70 in mind, agreed to let him work on the basis of the mid-engined Europa.

Giugiaro had already produced the attractive mid-engined Bora for Maserati, and was working on the very angular, but startling advanced Boomerang project on the same chassis, so he was familiar with the challenges inherent in mid-engined layouts. To put it baldly, the very first Giugiaro style for Lotus was on the basis of a much-modified Europa Twin-Cam chassis, but since the Type 907 engine was soon to be installed, and the track and wheelbase dimensions were also altered, it is easy to see how Colin Chapman’s mind was working.

The Europa’s wheelbase was 7ft 7in, and its widest track was 4ft 5.5in. Equivalent dimensions planned for the M70 – which did not have a name at this stage – were 8ft and 4ft 11.5in, respectively, so it was not surprising that the chassis supplied to Italy, thus lengthened and widened, was not Lotus’ final word on the subject. Work began on the style in mid-1971, and was completed before the end of the year, not as a running car, but as a full-size mock-up in display trim.

A second car, not only with doors which opened, but with a more advanced and integrated design of chassis, followed in 1972. It was the original silver painted car – now remembered at Lotus, logically enough, as ‘the Silver Car’! – which made its public debut on the Italdesign stand at the Turin Motor show of November 1972. Even at this stage, Giugiaro had dubbed it ‘Esprit’, defined by the Concise Oxford Dictionary as: ‘sprightliness, wit’, and students of styling evolution will want to be reminded that it stood alongside the Maserati Boomerang at the show. The first Lotus-chassis Esprit, actually being on a much-modified Europa Twin-Cam chassis, which Giorgetto Giugiaro showed on this Italdesign stand at Turin in November 1972. The screen on this first car was even more sharply raked than the production cars were ever to be. The Maserati Boomerang alongside the Esprit shows signs of the same style thinking by the talented Italians.

Something, for sure, was already on the move, and it was not long before motoring enthusiasts began to put two and two together. Mike Kimberley recalls that Lotus’ reaction to the completed prototype Esprit was so favourable that a design and development team was immediately set up to work with Giugiaro, and they stayed in Italy for a least 18 months. Chapman and Kimberley flew to Turin at least twice a week, during which the body style was refined and turned into a producible proposition. After the tremendously favourable public showing of 1972 there was a considerable lull while mechanical design commenced, though in the Group Lotus company report published in mid-1973 one of the three pictures published under the heading ‘The Coming Generation?’ was of the Giugiaro prototype, which had already been adopted by the company.

The first true production prototype was nearly completed by Christmas 1974, and was actually driven to London’s Heathrow Airport to meet Colin Chapman when he returned from the Argentine Grand Prix in January 1975. Indeed, by this time, Lotus had confirmed that the Esprit would be launched during 1975.

The Engine

The design and evolution of the new Type 907 engine was always intended also to be used in Lotus’ new mid-engined car. It was, of course, an ideal package for the Esprit, compact in length, wide but not high, and – considering the power output – a very light unit. Both the cylinder block and the cylinder head were cast in aluminium, which was ideal for the Esprit, where there was bound to be a weight bias towards the tail. For the original Esprit, therefore, Lotus specified a 2-litre version of the new 16-valve, twin-overhead-camshaft engine.

As fitted in the Esprit’s engine bay, behind the cabin, its installation and tune was exactly like that adopted for the front-engined cars. Complete with two twin-choke Dellorto DHLA carburettors, it was rated at 160bhp (DIN), and was installed with the cylinder block leaning over at 45deg towards the left side of the chassis. Unavoidably this meant that there was a slight weight bias towards the left side of the car, but not even the most experienced testers could pick up any effect on the handling so this detail was speedily forgotten. To provide more interior passenger space and to allow for the use of the more bulky Type 907 engine, the wheelbase of the M70 was to be 8ft, or 5in longer than that of the Europa which it would replace.

It was also destined to be a much wider car than the Europa, though it was always intended to feature a steel backbone chassis-frame. Right from the start, Lotus’ biggest problem was to find a suitable gearbox, and this was critical to the entire project. Since the Type 907 engine pushed out 140lb.ft of torque, even in 2-litre form – and the highest figure reached by the ‘Big-Valve’ Lotus-Ford twin-cams had been 113lb.ft – it was clear that the five-speed transmission from Renault, as used in the Europa Special, would not be strong enough for the job.

With the general layout of backbone frame chosen, the engine and transmission design finalized and the front suspension basically being the same as that fitted to the Opel Ascona/Vauxhall Cavalier, the rest of the mechanical design soon slotted into place. The independent rear suspension was as simple as possible; the fixed-length driveshafts doubled as upper transverse suspension links, combined coil spring/damper units were chosen, and large box-section semi-trailing radius arms helped to locate the wheels along with lower transverse links.

Steering was by rack and pinion – but without power-assistance, no Esprit, not even the Turbo, ever having needed this – and the dual-circuit Girling brakes had front and rear discs, solid but not ventilated, with rear discs mounted inboard. There was no servo assistance. Wheels were cast-alloy 14in diameter Wolfrace items, with 7in rims at the rear and 6in at the front. Much work went into productionizing the startling Giugiaro shape, not only to make it easier and cheaper to build in quanity, but to make it meet all the regulations likely to face such a car in the mid-seventies. The most significant change was to the angle of the windscreen. On the original ‘Silver’ prototype the screen had been angled at a mere 19deg from horizontal, and to meet the regulations this had to be lifted to 24deg 5min. Colin Chapman, however, did not give in without a fight, and the production Esprit still kept the same dramatically swept screen pillars, a feature achieved by making the screen profile much less curved in plan than had originally been intended.

Pictures

Specs & Performance

| submitted by | Richard Owen |

| type | Series Production Car |

| production years | 1976 – 1980 |

| released at | 1975 Paris Motor Show |

| built at | England |

| body stylist | Giorgetto Giugiaro |

| engine | Type 907 Inline-4 |

| position | Midship |

| aspiration | Natural |

| valvetrain | DOHC, 4 Valves per Cyl |

| displacement | 1973 cc / 120.4 in³ |

| power | 119.3 kw / 160 bhp @ 6200 rpm |

| specific output | 81.09 bhp per litre |

| bhp/weight | 167.89 bhp per tonne |

| torque | 189.81 nm / 140.0 ft lbs @ 4900 rpm |

| body / frame | Glass-Fibre Reinforced Plastic over Steel Backbone |

| front tires | 205-16×14 |

| rear tires | 205-70×14 |

| front brakes | Unassisted Discs |

| rear brakes | Inboard Discs |

| front wheels | F 35.6 x 15.2 cm / 14.0 x 6.0 in |

| rear wheels | R 35.6 x 17.8 cm / 14.0 x 7.0 in |

| steering | Rack & Pinion |

| f suspension | Double Wishbones w/Coils over Dampers, Anti-Roll Bar |

| r suspension | Trailing Arms w/Lower Links, Coil Springs over Dampers |

| curb weight | 953 kg / 2101 lbs |

| wheelbase | 2438 mm / 96.0 in |

| front track | 1511 mm / 59.5 in |

| rear track | 1511 mm / 59.5 in |

| length | 4191 mm / 165.0 in |

| width | 1867 mm / 73.5 in |

| height | 1105 mm / 43.5 in |

| transmission | 5-Speed Manual |

| top speed | ~199.6 kph / 124.0 mph |

| 0 – 60 mph | ~8.1 seconds |

Lotus Esprit S Price History

1977 Lotus Esprit S1 77030159H – sold for $20,900. Delivered by Lotus Cars USA to its first owner on the West Coast, this Esprit has always remained in that temperate environment, which shows in its outstanding original cosmetic condition. Displaying just over 27,000 miles on the odometer, which are believed to be original, this Lotus has been as enthusiastically cared for as it has been sparingly used.

Auction Source: The Amelia Island Auction 2012 by Gooding & Company

Lotus Esprit S1 Review

Motor, 29 January 1977. What They Said

With the introduction of the mid-engined Esprit at the end of 1975, Lotus completed the establishment of their new model range and with it their transformation into manufacturers of high-performance luxury cars in the Ferrari/Porsche class. The Elite and Eclat appeared as dual replacements for the Elan + 2, and now the Esprit, successor to the Europa, is gradually becoming available on the home market.

Despite being a two-seater, the Esprit is actually 1.75 inch wider than the Elite/Eclat, due perhaps to a certain extravagance in its conception, its glass fibre body being based on a styling exercise created by Giugiaro and exhibited at the 1972 Turin Show. For the same reason, possibly, the new bodyshell suffers from considerable visibility problems. The Esprit, however, is 1.75 inch shorter in the wheelbase, 10 inch shorter overall and 3 cwt lighter than its front-engined stablemates.

The Esprit uses a similar steel backbone chassis and the same water-cooled 16-valve dohc engine of 1973cc capacity to be found in all current Lotus road cars. With twin progressive-choke 45 DHLA Dellortos and a 9.5:1 compression ratio, it produces a health 160bhp.

Although the gearbox of the Esprit has five speeds, it bears no resemblance to the Maxi-based unit found in the other Lotus cars, but is supplied by Citroen, for whose now-defunct SM it was developed by Maserati. It also uses the SM linkage. Lotus have a supply contract with the French company for the next five years.

The Esprit has double-wishbone front suspension but unlike the other Lotuses, the hubs and links are taken from the Opel Ascona. The rear suspension, in which the driveshafts double at upper links, is traditional Lotus. Braking is by discs all round, mounted inboard at the rear.

Like all the new Lotus models the Esprit is very much more expensive than its predecessor. Originally estimated at £5000 at its introduction in 1975, inflation has increased the price to nearly £8000. Even at this level, however, the car is £2000-£5000 cheaper than other high-performance sporting cars such as the Porsche 911 N, the Ferrari 308 GTB, the Maserati Merak and the Lamborghini Urraco – supercars the Esprit matches in some respects, not in others.

It is too wide to swoop through traffic with the same cheekiness as the Europa and Elan, and it lacks the steering sensitivity of those two cars. On the other hand, its ultimate adhesion limits are so high that few owners are likely to find them, let alone get themselves into difficulties; if they do, they will find the handling very forgiving even on damp surfaces. It s mainly in the areas of noise suppression and visibility – plus a few other niggling faults – that the car disappoints.

Even so, we don’t doubt that the Esprit will be a sales success for Lotus for it is something of a trendsetter in sportscar design. However, we hope that development will make it quieter at certain speeds, and easier to see out of.

Performance

The twin-cam, belt-driven Lotus engine is very efficient, for from its 1973cc no less than 160 bhp is extracted at 6200 rpm, and it produces 140 lb ft to torque at 4900 rpm. This represents more than 81 bhp/litre which is a great deal more than most of its rivals can claim.

The Esprit we tested was not hampered by such encumbrances as air conditioning and the steering is not assisted, so with a lower weight and less power ‘leaks’, one would expect an appreciable improvement in performance over the other Lotuses. Indeed there is, though we could not approach the claimed figures of 0-60 in 6.8 sec or the standing quarter in 15.0 sec, which would really put the Esprit into the supercar class.

However, the time of 7.5 sec and 20.7 sec to 100 mph we got is still excellent. Up to 100 mph it feels quick, but thereafter the acceleration begins to tail off. We just managed to pull 120 mph within the confines of MIRA’s acceleration straight.

The Esprit is little slower on acceleration than many more expensive rivals partly because of its superb ability to get off the line so smartly. The traction is astounding – even when the clutch is engaged violently at high engine revs, the Esprit rockets forward leaving only short black lines on the road thanks to its limited slip differential which is a standard fitment.

Lotus claim a maximum speed of 138 mph, which we had no opportunity to verify. However, at 125 mph it had something in hand so over 130 mph is probably feasible.

Mid-range acceleration is very brisk, all the increments between 50 mph and 90 mph in fourth gear taking between 7.2 sec and 7.6 sec: this is the vital range for overtaking and the Esprit performs very well in it. Bearing in mind that top is intended purely for cruising, acceleration in this gear is not bad either.

Economy

All Lotus engines these days are identical in terms of power output and torque, so the only differences between the Esprit and the Eclat/Elite range are the lower gearing, weight and aerodynamics. Our touring figures of 25.2 mpg is poorer than we expected, for the Eclat managed 27.8 and the Elite 503 25.4 mpg.

Lotus have made a great play about the economy of their range. We achieved 20.3 mpg in the course of our test, quite good for a high performance two-litre car. Restrained driving could give over 25 mpg though we doubt if anyone would approach what Lotus describe as an ‘overall touring’ figure of 33 mpg. A reasonable range of 373 miles is obtainable from the 14.8 gallons contained in twin tanks.

Transmission

Gear linkage design is frequently the worst feature of cars whose engines are situated behind the driver. However, excellence with this configuration is by no means unattainable, as Porsche so ably demonstrate. The gearchange of the Esprit is even better – lighter to move and less notchy – and an improvement over that of the last Europa.

The gate is narrow with a short throw and the pattern is conventional, with fifth set over to the right, and reverse below it. Accidental selection of the latter is prevented by the necessity to lift the lever over an obstruction.

Fifth gear is described on the lever as ‘Overdrive’, an apt description of its nature though technically incorrect. At relatively high speeds in top, up to about 90 mph, the Esprit is quite economical and reasonably quiet. The other ratios are equally well suited to the characteristics and purpose of the car, being nicely spaced with maxima of 40,61,89 and 121 mph. The engine will not pull from below 40 mph in top, but it is much more flexible in fourth. The clutch is light and smooth.

Handling

The traction is almost beyond compare in a road car, even better than that of a Porsche, especially in the wet. The fat tyres are 250s all round, but they are 70-series at the rear and 60-series at the front on 7J and 6J rims respectively, instead of the differing tyre widths used in early versions. The limit of adhesion on dry surfaces is astonishing and even on wet roads it is very impressive.

The Esprit is an exceptionally safe car, though perhaps not so much fun to drive as the Elan Sprint. It does not respond to an extrovert tail-out driving style – indeed such an attitude is very hard to achieve; an increase in power merely increases the understeer, while lifting off in mid-corner provokes a mild tightening of the line.

Unlike the front-engined cars, the Esprit is not offered with power-assisted steering. Its rack and pinion system is nicely weighted but does not have quite the same precision as that of its forebears. It is a bit lifeless until lock is applied, and even then there is not quite the sensitivity and feel we had expected. On the other hand the car is astonishingly stable and runs arrow straight at very high speeds, the bib spoiler holding the front end down well except in strong cross winds.

Brakes

Large discs – inboard at the back – are fitted all round. The excellent servo has not impaired the sensitivity of the braking, which is stable and reassuring. Relatively low pedal pressures achieve 1.0g stops, and despite the fact that the pads began to smell, no fade showed up in testing.

Accommodation

The Esprit is designed to carry two adults and their luggage, and it fulfils this function better than most mid-engined cars. For tall and bulky people, getting in and out is rather awkward despite the wide doors, and in bad weather the cloth-covered sill over which you must slide gets wet and dirty; it’s also likely that your shoes will scuff the seat on the way in.

Once inside most people will be very comfortable indeed for although headroom is restricted, there is lots of legroom and the interior does not feel cramped for claustrophobic.

The huge rear door is hinged at the door pillar line and supported by a pair of struts. It gapes to allow easy loading over a low ledge, but the carpet of our test car was soaked with rain, causing severe internal condensation. The luggage area is generous for this type of vehicle, and a tonneau is supplied to shield valuables from the gaze of potential miscreants. A small amount of extra luggage may be stored in the nose section, which is mostly taken up by the spare wheel. Apart from the unlockable glove box and a small cubbyhole on the central armrest there is scarcely any stowage space in the passenger compartment, though flat objects may be squeezed behind the seats.

Ride Comfort

The Esprit’s ride is generally impressive, for major road surface irregularities are ironed out smoothly; only the occasional deep rut causes jarring. Once again Lotus have proved (if proof were needed) that it is not essential to sacrifice a civilised ride in pursuit of taut handling, or indeed vice versa.

Roll is virtually absent, there is no appreciable float, and hardly any pitch or squat even under severe braking and acceleration.

The only reservation we have about this aspect of the Esprit concerns a high frequency tremor – almost pronounced enough to be called a vibration.

At the Wheel

Drivers of average size will almost certainly find the interior of the Esprit very much to their liking. The stylish lightweight seats with their practical built-in headrests are nearly as comfortable as they look, and there is sufficient fore/aft adjustment in the runners. However, the backrests – which don’t give enough side support – are fixed so you are forced to adopt a semi-reclining position which not everyone liked.

Apart from restricted headroom, the larger driver may be put off by the interference of his knee with the comparatively large, non-adjustable steering wheel when operating the clutch; similarly, anyone with big feet will find the pendant pedals too close together. Nor is there much space between the clutch pedal and the central tunnel; a left-foot rest would be welcome. Moreover, there is a danger of depressing the throttle linkage crossbar while resting your left foot.

The relationship between the major controls is generally good, except for the handbrake, which is too far forward on the right.

Most of the minor controls are set into the neat instrument pod which must greatly simplify and reduce the cost of LHD conversion, and they are all within easy reach of most drivers though some will find the lefthand switches too far away. The lefthand stalk operates the two-speed wiper and the windscreen washer, and the indicators, flasher, main beam and horn are operated by the other. The coke lever and the electric window lifters are handily placed on the central console, behind the gear lever.

Visibility

Lotus have no doubt applied much thought to this knotty problem, but a great deal more will be required if they are to solve it, for it has many of the worst faults associated with a mid-engined car, plus a couple more caused by reflections in the division window and the rear side panes.

Forward visibility is awkward for parking unless the headlights are raised, though it is quite good otherwise, marred only slightly by thick pillars and light reflection. It is essential at all times to remember that not only is this a very wide car, but also that its widest point, over the rear wheels, is out of sight. Fortunately, a plastic scuff strip along the waistline protects the paintwork from minor scrapes.

The view out of the rear screen is acceptable once the car is on the move, but rearward and rear three-quarter vision is very poor indeed for reversing or manoeuvring in tight spaces. Emergence from angled side turnings demands a van driver’s technique. An additional problem we encountered was misting-up of the rear side windows, which do not contain a heating element and cannot be reached from the passenger compartment. Even the heater for the back window failed to cope with condensation from the wet boot carpets.

The single two-speed wiper has a broad sweep and the flat glass aids its efficiency, but a small area to the right adds to the blind spot caused by the thick pillar on righthand bends. The electrically lifted twin headlights have a good range on both dipped and main beams, but they suffer from vibration over bumps which makes them flicker.

Instruments

The Esprit’s Veglia instruments are attractively styled with green backgrounds and quite well calibrated. Two major dials – the speedometer and rev-counter – dominate the console, with an oil pressure gauge and water temperature gauge to the left and the fuel gauge and a battery condition indicator to the right, all these four instruments being semicircular. There is a display of warning lights running along the top of the console.

Heating

The heating controls, grouped on the right of the console, are clearly marked and easy to understand, though invisible in the dark. There are two levers which move in the horizontal plane, one for distribution and the other for temperature control which is progressive in its action. Even with the two-speed fan full on the output of hot air is not enormous, though once warmed up the heater copes well enough. Demisting takes a long time, and there is no provision for clearing the side windows.

Ventilation

Although directional control of the two face-level vents is admirable, there is little throughput. Exhaust gases wafted into the car in traffic takes a long time to waft out again, and usually it is advisable to open a window in such circumstances.

Noise

For nearly £8000 you’d expect peace and quiet and that any intruding noise would at least be a nice noise: the Esprit is disappointing in this respect. The engine cover does little to banish the loud boom that is particularly obtrusive beyond 4000 rpm. Even so, as fifth is so high, the engine remains fairly quiet when cruising at 90 mph. The transmission is relatively quiet.

Wind roar, poorly suppressed at speed, comes mainly around the door pillars. There’s also quite a lot of bump-bump over really rough surfaces though on the whole road noise is quite subdued despite the size of the tyres.

Equipment

The Esprit’s specification includes electric windows, a laminated screen, heated rear window, door mirror, hazard warning lights, inertia-reel seat belts and a two-stage panel light. What it does not include is a clock, rear window wiper and a cigarette lighter, all extraordinary omissions.

The attractive Wolfrace wheels are not, as may be seen from the pictures, matched front to rear. The spare is a front wheel and tyre so in the event of a puncture at the back caution must be observed. A small toolkit is supplied as well as the jack and wheelbrace.

Finish

The interior of the Esprit is plush and modern. Our test car was trimmed in brown suede-like fabric, colour coded to the cream brushed nylon of the seats. The carpet’s beige shade fell somewhere between these two. Surprisingly, the carpet in the boot is grey. There is an alternative of tartan and green cloth.

Despite one or two creaks and rattles in our test car, the Esprit is fitted out quite well, though we would like to see scuff-plates on the doors. We were not impressed by the flimsy sun visors or hinges of the glove box, while the positioning and size of the ashtrays renders them virtually useless.

The external finish is excellent, showing just how much Lotus have advanced in recent years.

In Service

After the first free service at 500 miles, Lotus recommend a minor service at 5000 miles and a more major overhaul at 10,000 miles. There are 70 Lotus dealers in the UK.

Self-servicing should not be too difficult. Minor attention may be given to the engine by raising the rear section of the engine cover, while for more major work, the entire cover may be removed. Most major components are within easy reach, though the oil filter and distributor are hard to get at. The battery is hidden under a removable shelf beside the offside rear side window. We noticed that parts of the rear chassis rails where exposed to the elements and one was already showing signs of rust.

Conclusions

Although much more expensive than the Europa which it replaces, the Esprit is between £2000-£5000 cheaper than other high-performance sporting cars and if this doesn’t ensure that it sells, the car’s striking looks surely will.

The performance from its modestly sized engine is excellent and up to certain speeds it is little slower than many of its rivals. It is also more economical, and though we expected better than 20.3 mpg the car achieved overall.

The car’s roadholding, braking and five-speed gearbox are all outstanding. Traction especially is almost beyond compare in a road car, even better than that of a Porsche, particularly in the wet. Only severe visibility problems mar this otherwise safe and satisfying car.

The visibility problems, exacerbated by side window condensation as a result of a soaked boot carpet, and excessive noise when extended, are problems which Lotus must urgently tackle. Those faults eliminated, Lotus surely will sell every Esprit they can make.

Classic Car – What They Said

THE Lotus Esprit, an out-and-out two seater with mid-placed engine, was first introduced in 1975. Its stunning looks are courtesy of Giugiaro and based on a styling exercise at the Turin Show in 1972 — so the design has worn well. A drag co-efficient of only 036 is claimed for the series 2. The body itself is glass fibre and made at Hethel and overall the car weighs just over the ton. Beneath the body a familiar Lotus steel backbone chassis is found. At the front end unequal length double wishbone independent suspension uses Opel Ascona parts linked to a Lotus rack for the steering. At the rear Lotus use trailing arms with the drive-shaft doubling as an upper link. Coil spring/damper units are used throughout. Brakes are by disc — inboard at the rear. The Lotus 2 litre engine has twin overhead camshafts operated by silent toothed belt and four valves per cylinder. It runs on a 95 to 1 compression ratio to produce a highly respectable 160 bhp at 6200 rpm. The unit is inclined 45 degrees to the nearside of the car and is contained under a metal cover in the luggage area which is separated from the passengers by a bulkhead. Colin Chapman clearly took his shopping basket around the European supermarket for, mated to the engine, we find a Citroen SM gearbox.

When the car was first reviewed tribute was rightly paid to the Esprit’s road behaviour but criticised on engine noise, visibility, poor ventilation and some minor points too. The S2, launched last autumn, is the answer to these criticisms but in this it has only partly succeeded.

One thing that has not changed is poor visibility as this is inherent in the design. Mid-engines are great in two seater sports exotica provided one accepts that the layout, while superb for road behaviour, has its disadvan-tages in poor luggage accommodation and visibility. Three quarter vision is traditionally bad and the Esprit is no exception — the windows behind the doors are of little help — so the electrically adjustable door mirrors are an essential aid. Forward vision is not so good either—even a six-footer can only see the lip of the sharply dipping bonnet at the base of the windscreen. The wings are out of view and the fact that the car is six foot and one inch wide is brought home when negotiating London streets and traffic jams. This makes it wider than an Aston Martin — itself a wide car — but it is made worse by the low seating position. After a while; of course, one soon learns to judge gaps but even so it would be preferable when traveling quickly on country roads, say, to be able to see clearly the car’s extremities. In these conditions the Esprit’s advantages in speed and road holding may be lost to a car of more manageable proportions. So too in city traffic the very lowness of the vehicle can present difficulties when emerging from junctions where there are parked vehicles, while filtering maneuvers need a van driver’s approach. None of these things are so serious as to mar the car but they do require the driver’s attention.

On the open road, however, the Esprit is pure joy, a driver’s delight. Steering is by rack and pinion and unassisted in view of the lightly loaded front end. It has the right weight and feel on the road, but some tendency to wander is more a feature of the 205/60 section Dunlop tyres nibbling at surface irregularities. At parking speeds the steering is just a shade too heavy. Ride is surprisingly good for a “driving machine” with only very bad surfaces intruding. Suspension movement is supple but well controlled, so that mid corner bumps do not unsettle the car. It would be very strange indeed if a Lotus were to be anything but exemplary in its handling — in this the Esprit does not disappoint. At the limit the car under-steers but backing-off the throttle converts this to easily controlled oversteer. To most people such attitudes on the open road will be purely academic even at the high speeds attainable. In these situations the car just steers. No car that goes as well as this can afford to be without good brakes. Again Lotus leaves nothing to chance — there are 97in discs at the front and 106in discs at the rear with servo assistance. The brakes are immensely powerful, with the rears locking first, and the overall pressures needed are light.

The five speed gearbox has top positioned on a dog-leg right and it is long-legged enough to be marked o/d on the wooden gearlever knob. The action is satisfying and quick at speed but a little less certain at lower speed, a blip on the throttle helps here. This whole process is made more satisfying by the padded backbone which locates the driver in addition to the seat and produces a relationship between gearlever and steering wheel and pedals rarely found outside racing cars. The seats, in optional ribbed cream leather were remarkably comfortable even though their rake is not adjustable, and there is sufficient fore and aft movement to satisfy a six foot driver. Entry into the seat is over a wide sill but door openings do not suit the long-legged.

Overall engine noise is very well suppressed in view of its proximity to the driver’s ear and it is the exhaust note which dominates. Person-ally I did not find noise levels excessive for this type of car, especially as the sound is eager and pleasant. It is true, however, that speech is made more difficult as the speed is increased. There are some disturbing reflections caused by the glass panel behind the driving compartment in both the windscreen and instrument glasses. These instruments live in a curved binnacle with the two major instruments directly ahead and minor instruments either side. Switches have fibre-optic illumination at night except for the heat/vent sliders which additionally are awkward to find behind the steering wheel and difficult to operate. Electric window lift and choke controls are found on the forward edge of the padded backbone behind the gearlever. The handbrake is efficient but poorly sited too far forward on the right-hand sill. There are comfortable inertia reel seat belts and a lidded but unlockable fascia glove box and a container between the seat backs suffices for internal stowage.

The front compartment contains the emergency spare wheel and tyre (these are of different sizes front to back on the Esprit) and space only for small items. Wiring and hydraulic pipes look a bit exposed. The release for this compartment is a bar under the dashboard on the driver’s side but it is apt to hide itself away completely when released. That for the rear compartment is a small T-handle in the offside door shut. This opens the large strut-assisted tailgate that extends back to the side window line. A tonneau protects luggage from prying eyes, and the engine cover unclips for access which is not a strong point. Fuel filler caps for the twin tank are not lockable — the tanks are connected by a balance pipe. The Esprit has separate side lamps and the head-lamps will raise and flash in one operation using the right-hand stalk. Strident horns are fitted; a single wiper lacks an intermittent facility but has two speeds, the faster being usefully so. This large wiper leaves an unwiped area to the right which enlarges the blind spot created by the pillar, and the parallel link bar flew apart but was quickly put right by Tim and Zoe Handles at Stoke. The engine is a little difficult to ‘catch” but warms up quickly — the choke appeared not to be connected on the test car. Heating is adequate but ventilation is still not over-good even with the noisy fan operating on second speed. Two ashtrays are provided on the sills but are poorly positioned and the lack of a cigarette lighter is surprising in this class of car, as is the lack of warning lamps or even reflectors for the large doors. I personally disliked the dark brown cropped velour, which covers doors and the large expanses in front of driver and passenger. It does not in my opinion fit in with the quality image Lotus is presumably seeking with this car but the leather seats break the monotony.

The top speed of this stunning looking motor car is a claimed 138 which seems entirely possible on the gearing and peak power is at 6200rpm. A 0-60 time of around 8 secs is respectable by any standards and the Esprit goes on to 100mph in a shade under 23 sec. Therefore our overall fuel consumption figure of 21.36 mpg which took in town driving, cross country, motorway and speed testing is highly creditable and demonstrates that super cars need not be environmentally embarrassing. At just under £15,000 as tested comparisons are difficult – there is really nothing like it at the price. If only Father Christmas would leave one in my stocking.

Autocar, October 1975 – What They Said

New Spirit at Lotus

Esprit – a new 2-litre mid-engined two-seater with Italian styling and a promising future

Autocar, October 1975

by Michael Scarlett, drawing by John Hostler

Elite, Elan, Europa; now Esprit – Lotus’s latest ‘E’. E for effort, since the button on this new design was pressed only 18 months ago, with the prototype being driven after overnight assembly to collect Colin Chapman from Heathrow on his return from the Argentine Grand Prix in January. E for Engineering – Advanced Engineering, Lotus, for whom the Esprit represents the first car to come from the work of Colin Chapman and Tony Rudd and their small team of engineers. E for esprit de corps perhaps – the Esprit is to be made à Volvo, by groups of men building each individual car complete rather than on a flow production line.

E for efficiency – aerodynamic efficiency, as witnessed by attention, almost unknown in most other car makers but typical of Lotus, to aerodynamic details like radiator ducting – and the roadholding efficiency of a low polar moment, mid-engine arrangement. E for elegance, even if it isn’t English elegance, but Giorgio Giugiaro’s. E for excitement – with a stated weight of only 18cwt and the 156bhp of the Lotus twin ohc 16-valve, light alloy engine, it has claimed 0-60mph time, one-up, of 6.8 sec, 0-100 in 22.7 sec, and a top speed of 138 mph. Besides ‘ghost, soul, mind, wit’, esprit also means ‘spirit’, which the car has lots of; driving the prototype at two stages during its early development when it was still not properly soundproofed was an exciting experience which made us look forward to getting our hands on the fully developed car.

You could call it a replacement for the Europa Twin Cam, which ceased being made in the spring. Passive safety requirements were one reason for the end of that stimulating early (and quite successful) experiment in series production, mid-engined sports coupés. The Esprit, though still dependent on an essentially backbone frame, is, like the current Elite, a car with thorough protection against all forms of serious impact. It is also a more roomy machine, with a degree more space for luggage, though not, it must be admitted, as clever in this respect as the Lancia Monte Carlo. Production is planned to start at 10 per week, with an intended maximum capacity at the Hethel plant of 40 to 45 per week. The first public view of the Esprit is on the Ital Design stand at this week’s Paris Salon de l’Auto; Esprits are to be shown at Earls Court.

Chassis & body

There is a chassis to the Esprit, a mixture of fabricated backbone like its predecessor and of tubular frame, partly sheet-braced. The backbone extends from its T-end in front, the extremities of which reach upwards like an Oriental dancer’s arms to carry the tops of the spring-damper suspension units. The rear end of the backbone tube broadens outwards to swell, as smoothly as space will allow, into the simple, near-fully triangulated space frame which carries the engine, gearbox and rear suspension. The Lotus engine in all its applications (Jensen-Healey, Elite, and some boats) lies on its exhaust side at 45deg. to the horizontal. This inclination takes up room on the left side, but allows space for a bracing tube across the top of the frame on the right, improving torsional and lozenging stiffness.

The body is naturally made the same way as the Elite, in Lotus’s still carefully guarded half-secret low pressure injection moulded glass fibre process. Like a toy plastic car kit, it is really two pieces, an upper and lower half, bonded together along the conspicuous waist line – a clamshell moulding. Happily, the naturally functional as well as presently fashionable shape of this type of car – convex sides – aids this two-piece construction; as any pattern maker will remind you, and as a child making a sand castle knows, there must be taper in a moulded shape to allow the mould to be raised, or the part to be extracted. There is at least one interesting difference from the Elite body, which will amuse Marcos owners. To form a roll protection bar immediately behind the seats, the firewall-bulkhead and roll hoop are combined in one diaphragm, with a hole cut appropriately for the short near-vertical window which divides the engine cover and thereby some engine noise from the cockpit. The Marcosian feature – or perhaps one should say De Havilland Mosquito-ish one – is that this bulkhead cum hoop is cut out of three pieces of 3/4 inch and 5/8 inch marine plywood. Possibly to anyone other than an engineer, a carpenter or experienced handyman, that may sound a little dubious; the point is however that in both compression and shear, the strength-to-weight ratio of plywood is very good.

At the front of the cockpit there is a box section across the car running between the bases of the A-posts and carrying the steering column, scuttle structure and door hinges. The centre tunnel also picks up on this beam. To prevent sides caving in during a crash, stout extruded aluminium-alloy narrow-box sections in the doors attach to the hinges in front and to burst-proof locks at the back, so that those inside are near-surrounded by both vertical and lateral rings of strength. The door beam extrusions have slots to carry the window lift motors and window frames – another typical Lotus multiple function use. Triplex laminated glass is standard (tinted is optional), Solbit-bonded for the flat windscreen.

Another piece of aircraft inspiration is seen for the radiator, inspired perhaps by Tony Rudd’s memories of Lancaster bombers he once flew. It is a bonded Covrad aluminium alloy type, unusually long and shallow, and mounted in a moulded space near the rear end of a venturi-like profiled plastic pod which hangs underneath the nose, bolted to the underbelly, and expanding in size from the small entrance as it nears the radiator. The radiator itself has a Covrad electric fan, thermostatically switched, which is placed at the hot end, where the water from the cylinder head enters. There is a 20 deg. C. drop in temperature across the length of the cooler, which speaks well both for the efficiency of the layout, and for that of the radiator; the similarly made (if not similarly shaped) Covrad type in the Elite has proved very successful, encouraging Lotus to stick with this supplier and material. Compared with almost all other cars, radiator air is thus ducted truly smoothly, and allowed to escape without any obstruction, or any tendency to heat up the front bulkhead.

There are two ‘lids’, the nose one which exposes spare wheel and some luggage space suitable for camera cases and squashy overnight bags, and the rear, gas-strut counterbalanced, which, released from the driver’s door frame allows you to get at the 7 cu ft boot and the dip stick, the latter without disturbing the engine cover. The cover is formed like a cap over the power unit. It can be slipped sideways out of its hinges and removed for the best access to the cylinder head. Persuading flat ‘bonnets’ to shut properly on both sides when their naturally flimsy shape makes them determined not to is difficult. Lotus have got around that bother this time BMW-style, by requiring the driver to close a lever under the facia which pulls the bonnet (the nose one) shut.

The two metal side tanks are best filled separately, in spite of their cross feed. They carry a maximum of 7.5 gallons each, and live between the bulkhead and back wheels.

The headlamps are two-to-a-side (halogen optional) and carried on a swing-up panels which are raised by connecting-rod linkages, electric-motor driven. The wiper is another single-arm type from this manufacturer, with a pantograph arrangement, which, thanks partly to the near-square proportions of the flat screen, clears a claimed 86 per cent of the area, compared with the minimum 80 per cent nowadays required by regulations.

Bumpers are mouldings for Europe, to which the Esprit is being introduced first, and will be foam-filled polyurethane for America.

Front-rear weight distribution of the car’s 2,015 lb unladen weight, with a half-full tank, is stated to be around 41.5/58.5 per cent.

Suspension, steering and brakes

At the front, Lotus have at present made use of Opel Ascona parts in the conventional double wishbone arrangement, which as this is the original Ascona, includes the anti-roll bar as part of the bottom wishbones (the latest Ascona relieves the anti-roll bar of location duties). One reason for adopting the Ascona parts, besides reducing cost for Lotus, is the brake disc which comes with it, which can be changed for a ventilated disc also used on some Asconas (should future developments demand it). The steering rack and pinion is an Elite one, with a shorter stalk for the opinion, and more quickly ‘geared’ steering arm geometry.

With no need to clear any rear seat pan, the Esprit is allowed to use a tidier version of the downward-offset Elite back suspension. The upper link is formed partly by a fixed length drive shaft. There is a new rear upright casting, which straddles the transverse bottom link centrally (where on the Elite the link is at the back of the bottom of the upright); the coil-spring damper however still holds the upright at the back. This bottom link is on its own. There is again a length fabricated diagonal box member fixed rigidly to the bottom of the upright by four bolts, but centrally disposed about the drive flange axis instead of below as on the four-seater. It forms a triangular member with the drive shaft, and because of that solid fixing to the upright, relies on the compliance of the inboard flexible bush to avoid any need for it to twist when the suspension deflects. By fitting the spring damper units with clips which hold them in the normal laden weight length during assembly of the suspension, ride height and attitude is fixed correctly when the inboard bushes are tightened, thus providing a small but – Lotus say – useful effect on these two variables.

The rear brakes, also disc, are inboard, relieving the suspension of any brake twist effects. They are larger than the front only because they have to clear the final drive sideplate bosses. The fact that it is inboard of course also takes away any drive twist effects, though not simple forces due to the same influences. At first, Lotus could not interest British brake makers in providing what they wanted in calipers; the German Teves concern were more than helpful instead, making exactly what was required. Late in the day, Girling offered to adapt the Lancia Beta caliper for Lotus, a quite hefty recasting being needed, at much lower price than the German one; the Girling one is accordingly fitted now. Each is bolted to a curious limb-like casting each side of the transmission; these double as rear engine-gearbox mount legs (Tony Rudd calls them the ‘dinosaur’s ribs’ though they would suit only very young dinosaurs, since Lotus do not go in for the unnecessarily mammoth). Hydraulics are twin circuit, without a servo.

Elite drive shafts and hubs are used, with the exception that the studding is different, to suit the Wolfrace GKN wheels. In the best interest of handling and traction, wider wheels and tyres are used at the back than at the front – 195/70 VR14 on 5.5 inch front with 205/70 VR14 on 7.5inch rear on the Esprit 700, and 205/60 VR14 on 7inch rims front with 235/60 VR14 rear on the Esprit 701, these being the most important differences between the two type numbers. The tyres themselves are steel-braced radial-ply tubeless, probably Goodyear G800+S Grand Prix, though Dunlops were also under consideration.

Drive

The only differences between an Elite engine and an Esprit one are tiny. The 95. 28 x 69.24mm, 1973cc light alloy unit is carried by two side mounts, plus two supports already mentioned for the gearbox. It has timing marks on the flywheel (where the Elite ones are on the front of the crankshaft) – so that you can see them more easily – and the water outlet elbow is on one side instead of forwards, because of the bulkhead. Lotus claim that the engine, a zestful unit spoiled only by too much harshness caused partly by an inadequately stiff crankcase, has been refined ‘by the experience gained from over 15,000 units’. Its four valves per cylinder now open to the orders of what the maker’s call their E-camshaft, which in sample drives we have had in both an Elite and the prototype Esprit, gives a most welcome and noticeable fattening to the middle of the power curve. The unit has passed American emission tests in the Elite; Lotus have an extensive and up-to-date emissions laboratory, which has helped them in this respect.

The transmission is bough from Citroen, who used it on their remarkable, now-abandoned Maserati-engined SM sports coupé. Citroen have guaranteed Lotus at least five-years’ supply of this fine transaxle, which has five speeds, all indirect. It is mated with the Lotus engine via a Lotus-made bellhousing, which joins on the centre-line of the differential. Using the Citroen one plus an adapter plate required too much precious length; Lotus bore their bellhousing in situ with the assembled suitably protected transmission – quite a game, but it works. The gearchange uses a rod to select the gears and a cable to work the across-the-gate movement. Unlike the Citroen-Maserati there is not a clonking gate, just a free lever, which provides one of the very nicest mid-engine gearchanges we have so far met.

Very careful choice of engine mount Silentbloc blonded mount Silentbloc bonded mounts has ensured that there is just the right amount of throttle and clutch cushioning, at any rate on the prototype, without what an American importer calls ‘Lotus leap’. This was obviously a tricky job at the back mounts on the transmission, which because of the need to avoid any undesirable influences on the camber of the suspension (via the drive shaft) had to have very stiff compliance laterally, but relatively slack movement vertically. Maximum revs are limited to 7000rpm as before with an ignition cut-out, allowing speeds in the intermediate gears of 40, 60, 89 and 120 mph in the case of the Esprit 700 fitted with the higher 4.375 one.

At the Motor Show, the Elite will be seen for the first time in 504 form, with the Borg-Warner Type 35 automatic gearbox. The same option will eventually be offered on the Esprit 704, since Citroen had got together with Borg-Warner to adapt the Type 35 to their needs in the SM. A 703 Esprit would be a power-steered one, which seems unlikely at the moment since the car does not have steering that can be called heavy.

Cockpit

Most notable feature of this is the somewhat ‘dream-car-like nacelle for the instruments. It is a printed circuit affair, connected to the central loom running down the backbone by a plugged single leg. Cleverly, changing from right to left hand drive on the production floor is basically a matter of swapping the lidded glove locker with the nacelle (and moving the steering of course), which each have similar fixings. The top of the nacelle forms a cover which can be removed for minor servicing, like bulb replacement.

Each wing of the cluster carries switches – lamps, panel, interior lamp and hazard flashers on the left, and the simple two-lever heater control plus blower fan and rear defroster on the right. On the left side, there is a lone air outlet to cool the driver’s face. Flanked by oil pressure and water temperature on the left and by fuel gauge and battery volts on the right, the two main central dials are a tip speedometer reading to 160mph and an 8000rpm electronic rev-counter. The trip reset is in between, and instruments are Veglia-made, from Italy.

Seats are typical of this type of car – couch-like, permanently reclining without any rake adjustment; the steering column is at the moment fixed too, rather than telescopically moveable, and the only adjustment available is of fore-and-aft seat position, with a ramp to lift it for shorter drivers. There is a useful range of this last movement, but no great amount of space behind the seats when a tall driver is using the car, as in other mid-engined coupés.

The view in front is extraordinary – the first thing you can see over the bottom of the screen rail is rushing road; this is not because the rail is too high, but because of the shortness of the drooping nose. Screen pillars are naturally quite thick, for structural and safety reasons, but do not block vision as much as they would have done on the original Giugiaro proposal, which had a shallower screen. Lotus changed the screen rake to a more practical angle.

Design history in brief

The first Esprit was a Giugiaro design study shown at Turin in 1972, the result of a conversation between the stylist and Colin Chapman at the previous Geneva show. It had the entire tail lifting up and the steeper screen. But design and development of the car is the work of Tony Rudd, Engineering Director in charge of Advanced Engineering, and his team, with Chapman intimately involved the whole way through. It is very much a team, each member doing the other’s work at one time or another, typically of the much healthier atmosphere of a small concern compared with a huge department of a much bigger company. When the first road-going prototype was being assembled in January, everyone was hauled in to building, including Ralph Bellamy who was supposed to be getting on with other work for the rear end of Lotus Grand Prix cars, and Rudd. It was finished a 1am, leaving at 4 in company with an Elite to be driven to London Airport to meet Lotus chairman Colin Chapman, who was returning from the Argentine Grand Prix, so that he could drive it back to Norfolk.

Prices were to be announced after this went to press; this should be the cheapest Lotus. Having driven only the prototype, we should not talk in detail about impressions of the Esprit, except to say that regardless of inevitable noisiness in a machine still in the early stages of development, it clearly has the makings of one of the very best Lotuses there has ever been – very fast, very safe, and very great fun. We look forward to Road Testing it.

Road & Track, 1977 – What They Said

Chapman the alchemist turns a show car into a reality

Colin Chapman’s mid-engine Esprit seems long past due, most likely because it would appear to be the natural cornerstone of the Lotus line, especially in the wake of Mario Andretti’s win at the Long Beach Grand Prix. Yet the Esprit is the last of the revamped Lotus line to reach production, the new front-engine Elite introduced here in 1975, followed by the Sprint about a year ago.

Continuing readers should be familiar with the Esprit’s gestation, starting as a Giugiaro design project for the Turin Show in 1972 and being introduced as a production car at the Paris Show in 1975. Little of the car’s basic styling has changed since the first show car, which is a credit to Giugiaro, Chapman The Chairman and his right-hand man, Mike Kimberly, who saw the project through to production. Where other show cars remain an unattainable figment of our automotive dreams, cars like the Lotus Esprit become examples of what happens when the dreams are founded on real-world specifications. Lotus-watchers will tell you the production Esprit was a logical assumption when they first saw the show car, as The Chairman is not about to waste his money on mere figments of anyone’s imagination . . . even his own. Which is fine with us, as what’s important here is that the Esprit is a real automobile, not just fibreglass and aspirations.

And that fibreglass is quite good, the body on our yellow test car being smooth and well finished. This is done in the rather exclusive Lotus process in which the body paint is sprayed into the moulds before the glass in introduced. The advantage is not only a rich colour, but also repair of minor dings with a fine sandpaper and rubbing compounds. The disadvantage is having to paint whole sections after repair rather than being able to spot paint. The body is composed of upper and lower sections joined at the rub strip that runs the length of the body. The only apparent external difference between European and American models is the larger front bumper, which makes up most of the 2.7inch difference in length between the two Esprit versions. The inapparent difference is the extra 300 odd lb the U.S. versions add over the others, that being taken up in the bumper systems, extra body structure built in front and rear and other “federalizing” necessities such as emissions equipment.

You can imagine the attention the Esprit’s shape draws and we can suggest it to any young bachelor (the suggestion based solely on observations, not experience, mind you), especially in red or yellow. There are designers, General Motors; Bill Mitchell and Porsche’s Tony Lapin in particular, who feel the wedge shape is a fad at best and a dead issue at worst. The car they usually cite as evidence is the poor-selling Ferrari Dino 308GT4, but the Lotus has a much lighter look than the Dino. We wonder if the wedge shape, instead of being a passing item, isn’t a modern classic in its own right.

The Esprit’s interior has the same sort of visual appeal as the exterior. While the car can be had with its insides done up in beige with a contrasting dark brown, our test car had the green and orange Scotch plaid Esprit decor. Completely done in cloth, the interior is a striking setup with individual cockpits for driver and passenger and a dashboard that slopes forward enough towards the passenger to give a passive restraint safety-car feeling.

There’s a wraparound instrument panel with easy-to-read gauges mounted in the center, using white numbers and pointers on a medium green background and thankfully not done in one of the English national typefaces. All lighting control switches are on the left of the panel, with the light control stalk on that side of the steering column. “Environmental controls” such as the fan and ventilation levers are on the right side, along with the stalk for the windshield wipers and washers. One staffer thought of the setup as an interesting, different design, while another considered it gimmicky, though perhaps the main thing is that all the instruments are easy to read and the switches available without having to take your hands far from the steering wheel.

The only controls you’ll have to reach for are the choke and electric window switches, mounted on the center console just aft of the shift lever. Lotus has done a very nice job with the shift linkage, especially when you consider the distance back to the Citroën (ex-SM) 5-speed gearbox. Fore-aft movement of the lever are rod actuated and crisp, but most drivers occasionally had trouble with reverse, getting hung up in the cable-operated left-right movement.

As you can probably tell from the photos, the seats are not the type one settles into deeply, though they hold you firmly enough for all purposes. While no one had trouble getting comfortable in the car, a few missed some sort of tilt adjustment to go with the seat’s forward-backward movement. Also, the head restraints are a bit too vertical, forcing the driver’s head right up next to them. All drivers had problems with getting their feet tangled in the closely-spaced pedals, the problem aggravated by a ledge to the left of the clutch that catches that foot on its way down making it difficult to fully depress the clutch. Worse yet, a too-high throttle made heel and toeing a guess at times. Perhaps Lotus should throw in a certificate for a pair of pointy Italian shoes.

Joining these are a few other problems, such as an awkwardly positioned handbrake (front of the left door sill), but generally they are things that can be adapted to the are fairly obvious when taking a test drive. There is another problem we see no easy solution to: interior heat. First, there is virtually no ventilation. One vent is on the wraparound instrument panel, another far forward of the passenger and nether pumps enough air, even with the fan on its high setting, to be of much help. Then there’s the problem of cockpit heat, coming from the front radiator and the tunnel-mounted coolant pipes. The problem would be lessened if the car was equipped with the optional air conditioning, but it better be very good model as it has to cope with summer temperatures, both in the cockpit and the radiator.

Once past that problem, the Esprit’s driving environment is an enjoyable one. The sounds from the engine compartment are fairly well shielded by the car’s plywood bulkhead, the only annoyance not being total noise, but certain resonances that come through in certain rpm ranges. For instance, at 30mph the car is quieter in 4th gear than in 5th. Still, it isn’t the sort of car one has to shout in to be heard and the sounds are generally of the busy-engine sort the driver would like to hear.

There are two other compartments in the car, of course, the one up front for the spare tire (front size) and the pieces necessary to change it, the master cylinder for the brakes and so little luggage space you’d have trouble stowing much more than your pointy Italian shoes there. In the back compartment, this one under an ill-fitting hatchback with no lifting handle. Here there’s a little more luggage space around the engine cover, covered by a tonneau that snaps into place. We suggest potential buyers start looking for soft luggage that can be fitted in the around things. The engine cover is held in place by four elastic straps and is fairly easy to remove which is good since Lotus expects you to remove it to check oil. Happily, the American Lotus distributors are adding a little hinged hatch cover for ‘access to the coolent header tank and dipstick’.

The Esprit engine is, of course, the same one installed in both other Lotus models, the Elite and Sprint nee Éclat. At that, it is a four cylinder trying to play in the leagues with V8s and V12s and basically it does so very nicely. With 1973cc, twin camshafts and four valves per cylinder, it manages 140bhp to 6500rpm and 130lb ft of torque at 5,000rpm. That horsepower figure is down from the European version’s 160, but then so is the compression ratio from 9.5:1 to 8.4:1 and, more importantly, the timing. The result is an engine that will get the Esprit to 60 in 9.2 sec (equivalent to the last Maserati Merak we tested), but which is obviously emissions stifled and hates to idle. From cold the engine starts easily with just a bit of choke, but when hot it requires some grinding and stumbles when lit. There isn’t much power going up to 3000rpm, but then the engine takes off – it’s almost like turbo lag – and the care once again becomes a delight, the engine willing to rev despite air injection and a catalytic converter. Then again, if you’re driving the Esprit in the manner it likes, you won’t be spending much time below 3000rpm, And while hot starting is a problem, this isn’t the sort of car that delivery men will be buying. Incidentally, Lotus specifies Mobil 1 synthetic oil for the Esprit.

With its 2350 lb curb weight and 5-speed gearbox, the Esprit was able to eek out 27.5 mpg on the mileage course we ran in the Lime Rock area. Allowing for the differences between the route and the one we use in southern California, that number is probably 3-4mpg higher than we would have gotten here, but even that lower figure is quite good for a performance car, regardless of where it was run.

While such items as straightline performance and fuel economy are important in the total Lotus equation, the prime ingredient is handling. This is the reason Lotus owners are willing to live with such things as a lopy idle, little luggage space and poor ventilation. Hung on both ends of the Esprit’s boxed backbone frame is what has to be about the best suspension combination on the road today. In front you’ll find Opel Ascona upper A-arms in combination with transverse lower links, their fore-aft location secured by the anti-roll bar. The rear suspension is homegrown, with fixed-length half shafts as upper arms, lower links and semi-trailing arms. Tires are an interesting mix, 205/60VR-14s in front and 205/70VR-14s in back, their respective pressures being 18 and 27 psi.

When you first drive the Esprit, the front end feels light, so light you’re sure the car will understeer. Yet drive it into a corner, flick the wheel and the car responds quickly. The Esprit isn’t neutral, but starts with mild understeer, moves gently to neutral and then just as gently to oversteer if you want it to. The car is very forgiving and reacts quickly to any steering input, but never snaps back with too quick a reaction. And it does this not only on smooth surfaces, but over bumps as well. Because it has relatively soft springs, you don’t have to take our your dentures as the ride will not jar your teeth loose, even on railroad crossings, because the Esprit is one of the best riding mid-engined exotic’s sold.

Brakes are a critical part of any such car and the Lotus 4 wheel-disc system almost matches the handling of the car. Why almost? Because while the Lotus handling is superb, the brakes fall a bit short of that mark. They do get very high points for control under heavy braking and we experienced no fade during our tests, yet the distances were a bit too long, even for bumpy Lime Rock, where we expect longer stops because of the track surface. To put the brake question in perspective, though, for the average driver enjoying himself on a winding road we’d be more concerned with brake pedal placement than the car’s overall braking ability.

One encouraging note is that while our test Esprit did suffer from a few quality control problems, they certainly weren’t in the epidemic proportions of some past Lotus’s. This time it was more the bother of things out of adjustment – such as pop-up headlights that jitter nervously – or not quite fitting, rather than the major disasters suffered in previous Lotus test cars.

It is always necessary when finishing a road test to take a step back from the test car and try to put it into perspective. That is difficult with cars such as the Esprit, because when held up against most of the plainer cars we test, the exotics lose points in areas such as sound isolation, luggage space, entry and exit and the like. Looked at through that filter, the Esprit appears difficult to live with and that hardly allows for it not having the minimal level of ventilation we expect from every car we test.

But at this point the importance of the square-cut criterion dims, because, Lord, is the Esprit fun. When the most functional, reasonable cars begin to fade from your memory, you can still easily picture the view over the Esprit instrument panel of turn one looming on the right as braking-point numbers flash by on the left. You retain thoughts before cutting back along the road that runs with the river. You remember the people who stopped to look and the mere average sports cars that tried to keep up with you through the curves. We’ll be the first to admit that taken in total there are many cars on the road that are more practical than the Esprit, but there are few that are as much fun.