No racing car exemplified and exploited the admirable freedom of the Can-Am series rules more than the 1966 Chaparral 2E. It introduced new aerodynamic concepts that were game-changing, though it took a while for others to catch on.

Jim Hall’s Chaparrals were the cars to beat when the Can-Am series was born. In the SCCA’s U.S. Road Racing Championship, the amateur series that predated and later paralleled the Can-Am, the Chaparral 2A had been almost unbeatable. Their outstanding success in 1964 and 1965 in the USRRC helped make them top Can-Am favorites. At that time Hap Sharp, a partner in their company Chaparral Cars in Midland, Texas, shared the driving in the two-car team with Jim. Older than Hall, Sharp was a source of good ideas, which, bounced against Jim’s engineering education at Cal Tech, and produced results.

As an example of their pace, before the USRRC race at Watkins Glen, in 1965, Dic Van der Feen of the SCCA took Jim Hall aside and pleaded, “Couldn’t you just take it a little easy this time and not lap the cars behind you? It makes it look so bad when they’re lapped.” Jim allowed as how he’d think about it, then went out and, under pressure from Hap, went so fast that the third-place car was triple-lapped! When he saw Van der Feen after the race Jim struck his forehead and rolled his eyes skyward: “I’m sorry, Dic. I forgot all about it!”

However, some forces were working against Jim Hall. In 1966, he was making his first big attempt to win races in Europe with Chaparral coupes, an effort that took far more time than he had expected. The 2D coupes were their USRRC roadsters, with glass-fibre tubs, rebuilt for long-distance racing. One of them won the Nürburgring 1,000 Kilometres with Phil Hill and Jo Bonnier driving and Hap Sharp the team chief.

Also, 1966 saw the maturing of the first attempts by the British to build cars to use the big American V-8 engines that were on offer. With these behind their drivers, both Lola and McLaren became major competitors for the first time. But they were entering a field that for several years had been dominated by American-built, mid-engined specials, high-horsepower cocktails mixing Cooper and Lotus chassis, built for smaller engines, with Chevy and Ford V-8s. The Chaparral was the best of the all-new American cars that followed this first experimental stage.

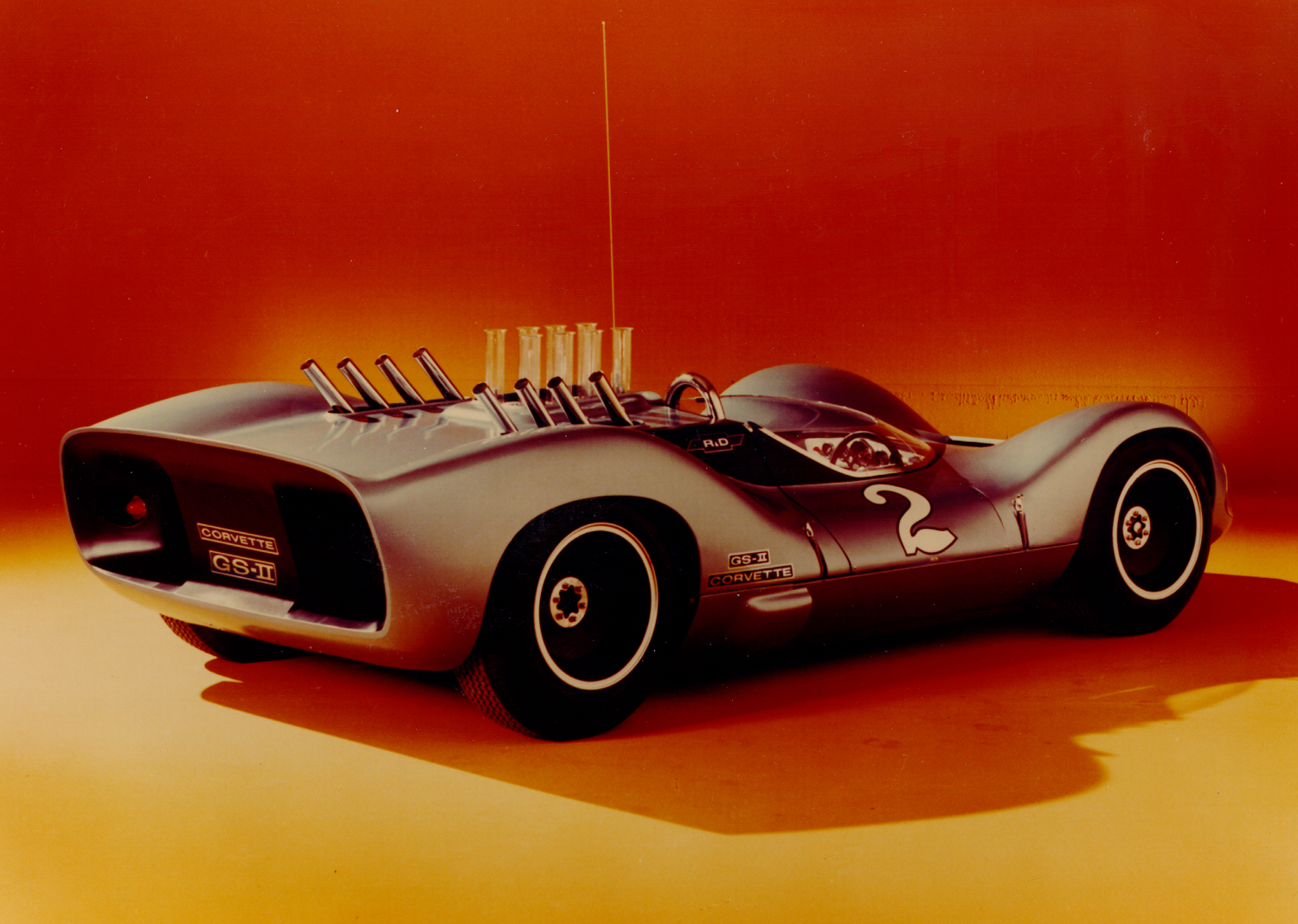

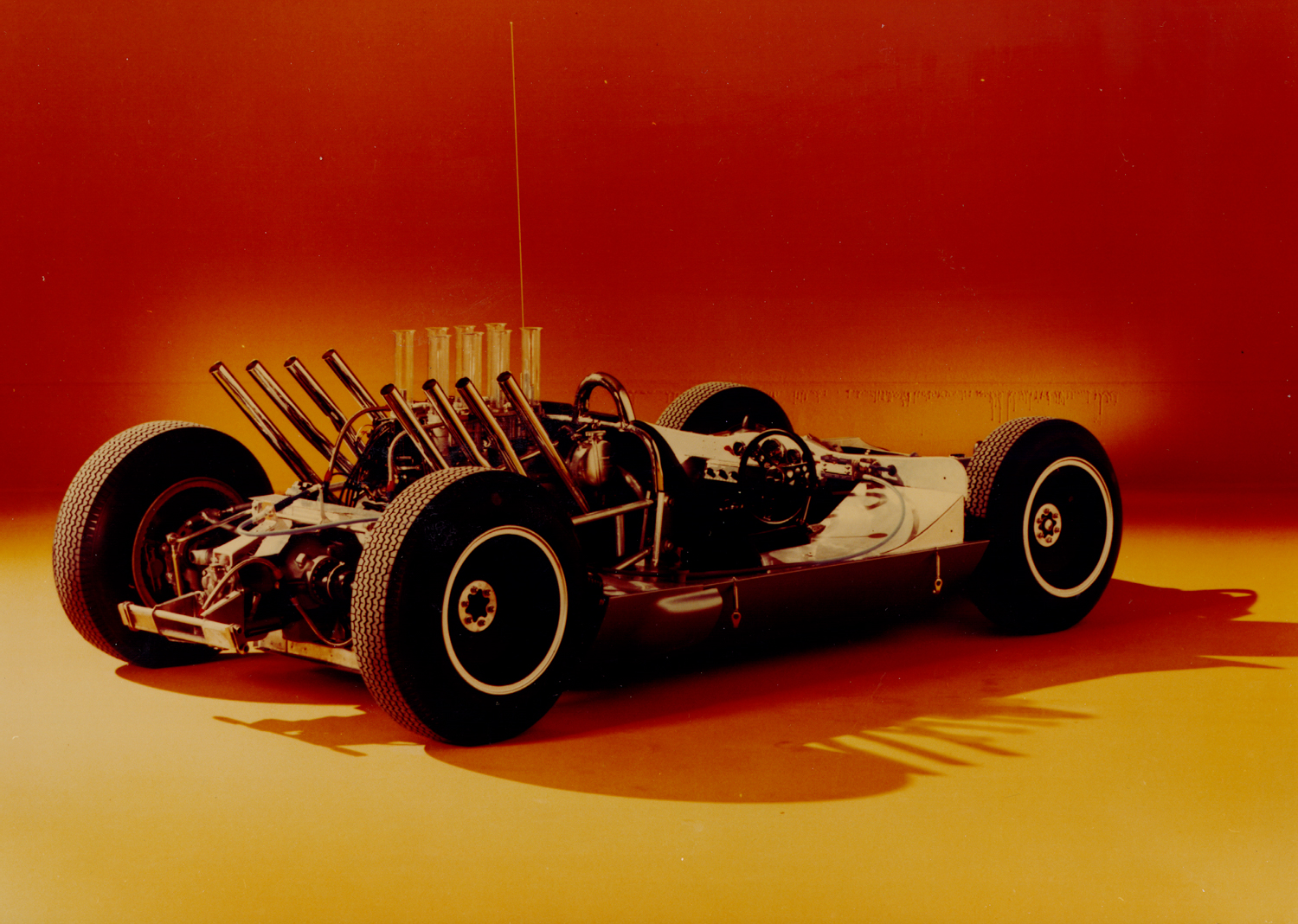

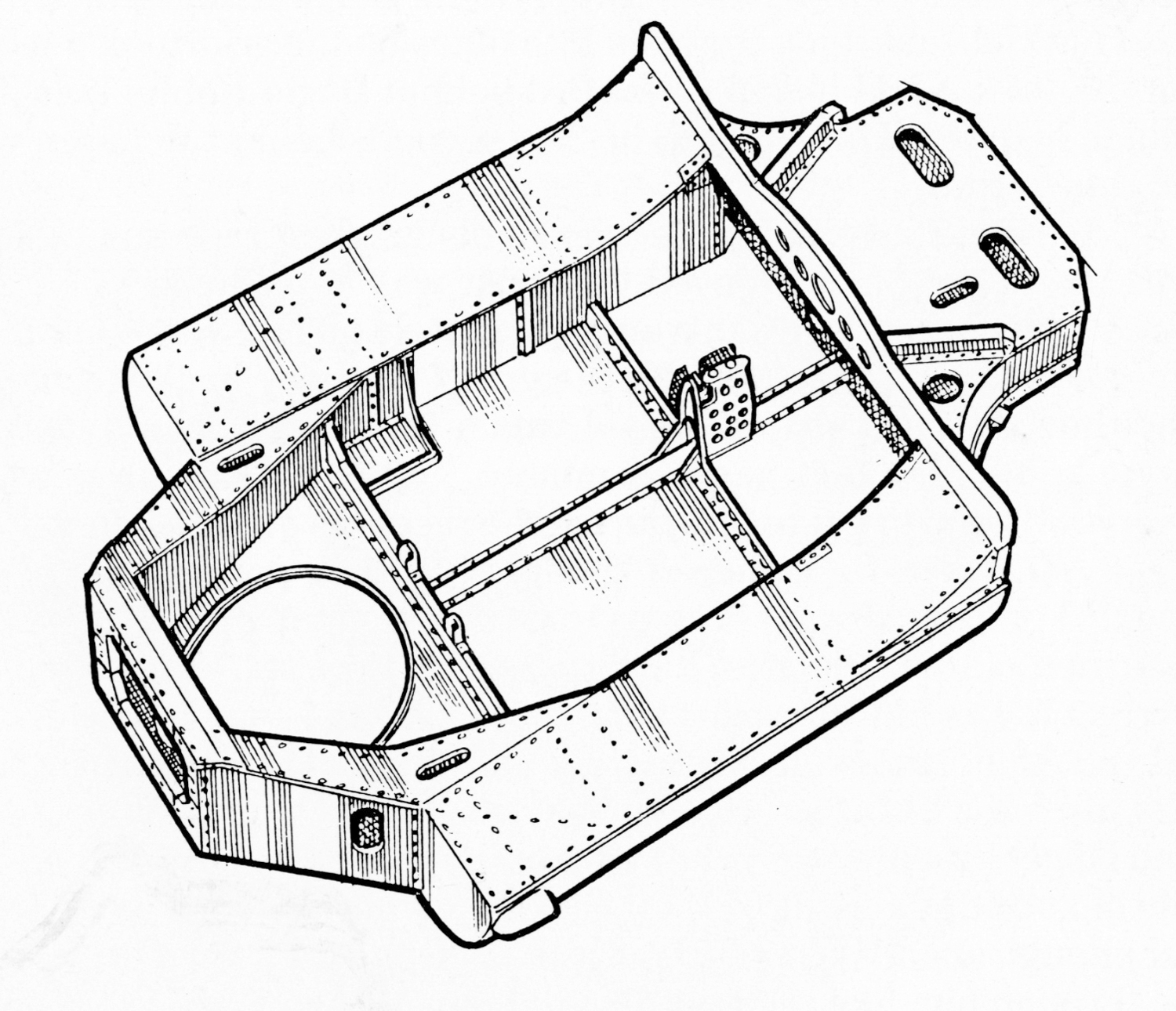

A couple of years earlier the Texans had forged a link with an arm of General Motors that was thrusting in new directions under the guidance of engineer Frank Winchell. This was Chevrolet’s Research and Development arm, to which Jim and Hap had been introduced by Styling chief Bill Mitchell. With their Corvair bits and pieces the R&D people had been experimenting with mid-engined chassis. In 1963, in a project headed by young engineer Jim Musser, they built an aluminium monocoque with racing suspension, the latest wide t-res and tuned engine that they called the GS-IIb. Its panels were riveted and bonded with a 3M adhesive that was oven-cured.

Weighing 1,450 pounds with ultra-thin GRP bodywork, the GS-IIb reached 198 mph at GM’s Milford Proving Grounds. With a racing-type car needing a racing-type track for testing in secret—not least from the eyes of GM’s officials and informers—R&D found the answer in Midland, Texas at Rattlesnake Raceway. This was a pear-shaped track that Hall and Sharp had built to test their cars. Hall saw eye to eye with Winchell, both preferring to work out of public view until they were ready to be judged by their creations.

“We had a test track right there where we could run,” Hall said later. “It was very useful. That’s probably an advantage that we had during those days. I could just go out and run during the mornings, say, and then come back in and make some changes, go back out in the evening and check it. I think a lot of the teams we were racing against in the ’60s didn’t have that capability.”

Toward the end of 1965, at the Kent, Washington USRRC race, a new Chaparral was introduced, the 2C. With its aluminum frame—its basis the GS-IIb tub built by Chevy R&D—it was a smaller and lighter car than the Chaparral 2A, whose rugged monocoque fibreglass frame weighed 140 pounds, more than double the heft of the 2C tub while being no stiffer. “It isn’t surprising that we changed to aluminium,” Hall remarked. “With fibreglass you were committed to that shape and size when you build moulds so you’ve either got to be very fluent or spend a lot of money to rebuild the mould all the time.”

A feature of the frame was that its cockpit-side, fuel-bearing sponsons were shallow by racing-tub standards. Though not deeply detrimental, this was intended to help entry and exit from the road car for which the frame was originally designed. A disadvantage of the frame from the drivers’ standpoint was that it amplified vibrations and stresses that the glass-fibre tub absorbed. These came both from the track and from the suspension’s anti-dive and anti-squat geometry, which fed impacts back into the frame. Drivers dubbed it the “EBJ” for “eyeball jiggler”.

More visible than the frame was another feature of the 2C, a driver-controlled rear spoiler. Large fixed spoilers had been steadily growing at the rear of sports-racers to the point where their drag was a disadvantage. The 2C had a big spoiler that defaulted to the erect position and could be made to lie almost flat by a push on a pedal to the left of the brake pedal. In the Chaparral this was easily done thanks to its radical transmission.

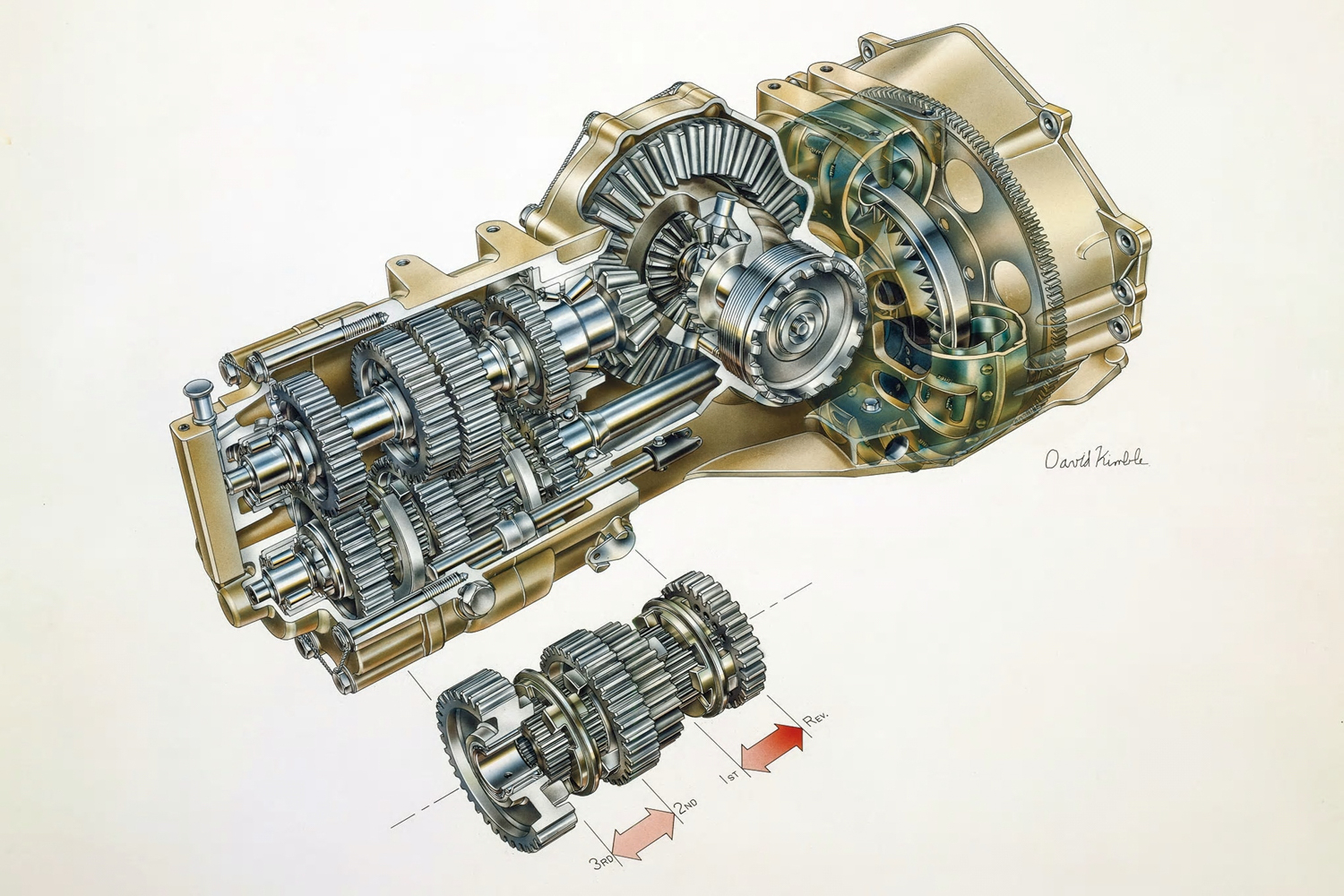

During 1964 it gradually became clear to rivals of the Chaparral 2A on the track that it had something different in the transmission department. They hadn’t noticed at first, which surprised Jim Musser: “I thought the sound of the car on the track would give it away. It had a Buick Dynaflow sound.” That wasn’t surprising because in principle the gearbox was identical to the original 1948 Dynaflow, which relied completely on a hydraulic torque converter to give a. 3.1:1 torque multiplication.

“The automatic transmission was Hap’s idea,” Jim Hall said. “He drove my first car, the Chaparral 2 that had a 327 Chevy, a big gearbox and quite small tires in those days. And it would spin the wheels in just about any gear up to fourth. And he said, ‘Well, what’s the transmission for?’ He got out of it and he said, ‘Why do we have a transmission?’ So that got us started.

“We thought, ‘Well, what if we use a torque converter to multiply torque for starting?’ We were working on that pretty hard when I got associated with a fellow at Chevrolet in Detroit who was in charge of Chevy’s R&D department. His name is Frank Winchell. He said, ‘Golly, I’ve got some ideas about that.’ He came up with that transmission for a prototype car that they built in 1964. And I tested the transmission in our car. It was very, very good and easy to drive. We thought it had a lot of potential. So they made a deal with us to let us test that as a piece of test equipment.”

“I feel this automatic transmission is the greatest innovation in auto racing today,” said Roger Penske, who was racing one of the Chaparrals. “We thought at first it might be a problem because of the wear on brakes when you can’t use your engine for braking. However, with the breakthroughs in brake technology and the better cornering power of the new tires you can go into corners faster without losing control. You can keep both hands on the wheel and go into the corner as deep as you want. You can use left-foot braking and save time between the start of braking and the return of your foot to the gas pedal.

“Jim’s transmission gives the engine increased life of 50 to 100 percent,” Penske added, “because there are no downshifts where you might have a chance of over-revving the engine when you are accelerating out of a corner. You don’t wind up and then drop down… wind up, drop down…then wind up until you finally get it in a high gear. With the automatic you have consistent rpm climb. There’s no quick acceleration of rpm unless you hit oil or water on the course where it will make the wheels spin. As long as the wheels aren’t spinning, you have constant application of torque and horsepower to the rear wheels.”

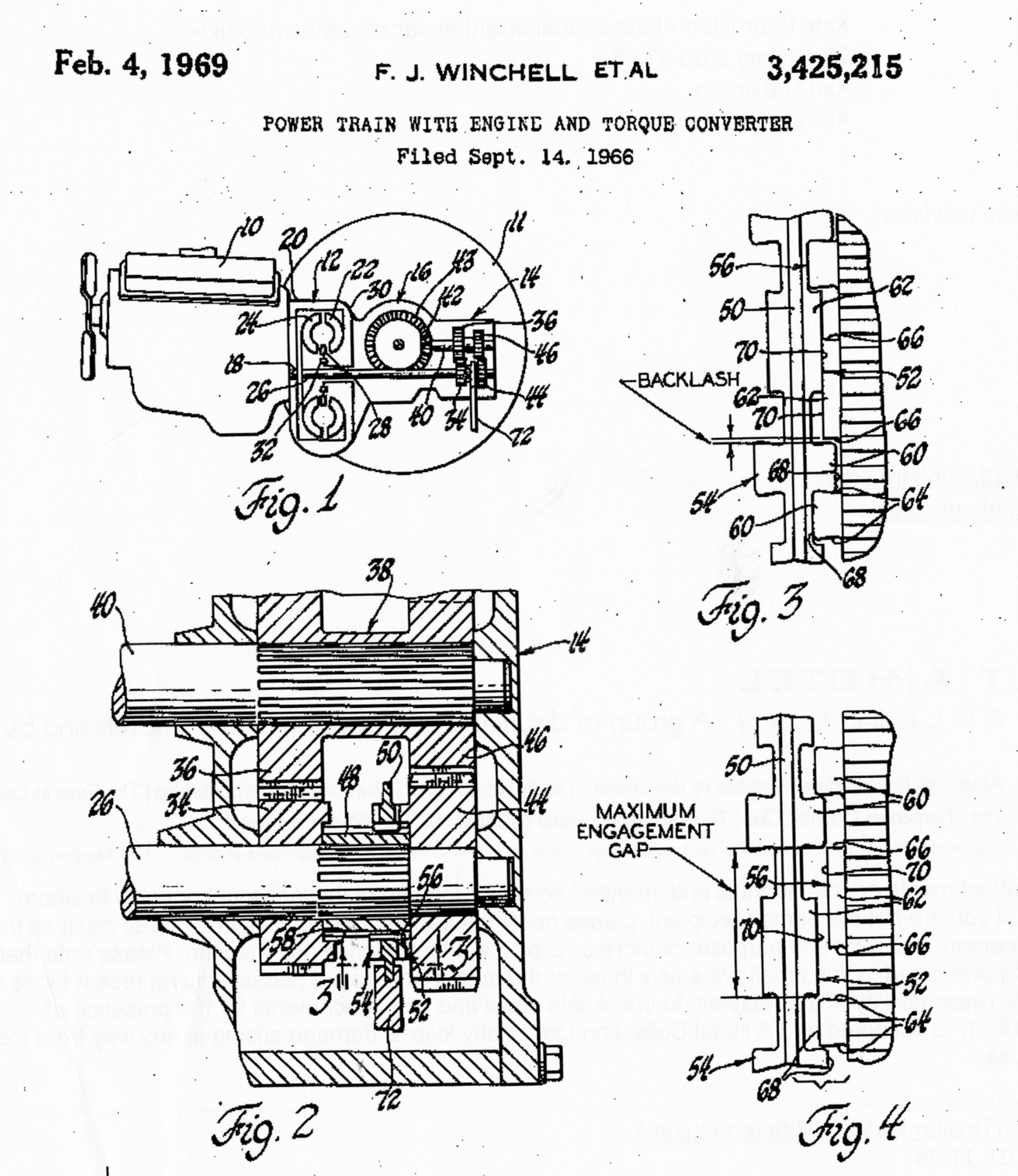

As described in the patent that he and Jerry Mrlik lodged on September 14, 1966, a further development of Frank Winchell’s transmission married a three-element torque converter with a two-speed manual shift. Winchell set out the concept of a transmission that could “maintain converter output torque and approximately peak engine torque throughout the speed range in which engine torque increases with increasing engine speed.” Also illustrated in the patent was the special design of face-dog clutches that made the box easy to shift without a clutch.

At first the gearbox—inspired by the quick-change center sections for Indy cars made by Ted Halibrand—served solely for forward and reverse. As tires improved, better starting torque was needed. For this and higher top speed, a second speed took the place of reverse. Finally, Chevrolet added a third speed when Chaparral competed in endurance events abroad. This was used in the 2E as well.

“This worked fine,” said 2E driver Phil Hill of the gearbox, “except it wouldn’t tolerate being yanked into gear while the car was stationary, even with the engine at a slow idle. You had to stop the engine, put it in gear and then fire it up again. The procedure for driving off was like this: engage first gear, then start the engine while holding the car with your left foot on the brake pedal, which was on the left and meant to be used with the left foot only. Release the brake and drive off. You could shift at any speed you wished into the next gear. You could even start off in second or third gear, though with less performance.

“Shifting did require actively getting it out of gear in that millisecond when the power let loose,” Hill continued, “and then smartly timing it into the next gear. It was as simple as that, with a conventional H-pattern shifter but no clutch. Downshifting, I’d lift a bit to take the pressure off the dogs, snick the lever into neutral, add a quick stab of revs and slip it down a gear. That sounds like a series of small events, but in reality it was one quick, easy, unforced motion.”

“Thanks to the torque converter in the 2E,” Phil added, “we had three ranges: zero to about 110 mph, 0-150, and 0-190. This added flexibility. You didn’t have to be continually changing up or down to get to the gear and range of speed appropriate for a particular part of the circuit. In the 2E, you were often able to leave it in one gear, without shifting as you would in an ordinary racecar.”

“There was only one drawback,” Hill admitted: “The combination of this gearbox with the torque converter meant that the 2E suffered off the line. Races had standing starts and the Chaparral couldn’t accelerate from a stop like an ordinary racecar. With a clutch you can store up some power in the flywheel and dump it through the clutch to the wheels to get off the line quickly. But you can’t build up that sort of force in a torque converter so we lost our advantage at the start. The difference was enough that although we could qualify in the front row, sometimes we’d be in the second or third row by the time we reached the first corner.”

The one-off Chaparral 2C was a proven user of the torque-converter transmission and foot-operated spoiler by the time Jim Hall drove it In the Northwest Grand Prix at Kent, Washington on 10 October 1965. Hall won both heats and overall in the 2C with Sharp second in a 2A. Satisfying as this would be for the team from Texas, it was destined to be Jim Hall’s last victory at the wheel of a racing car.

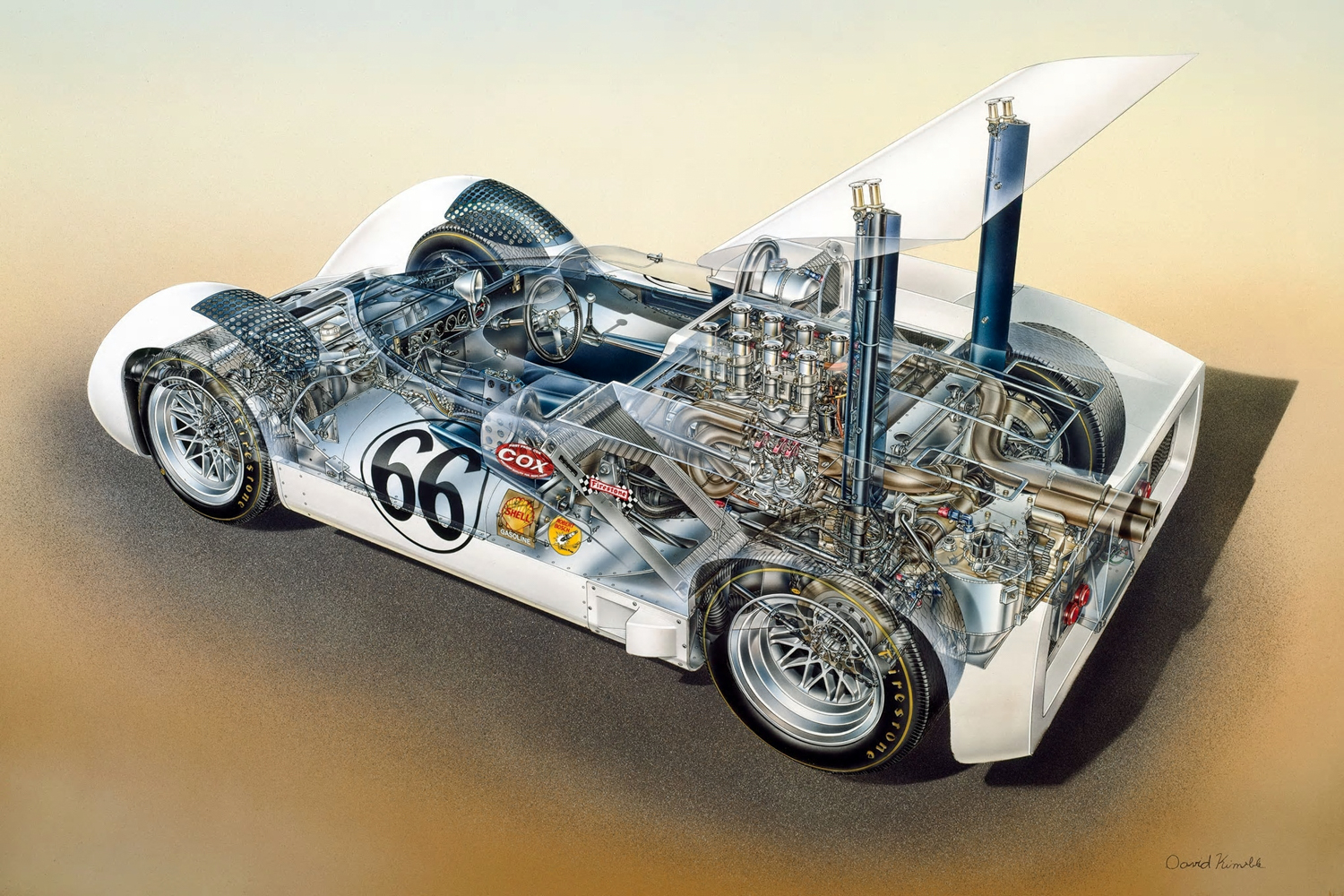

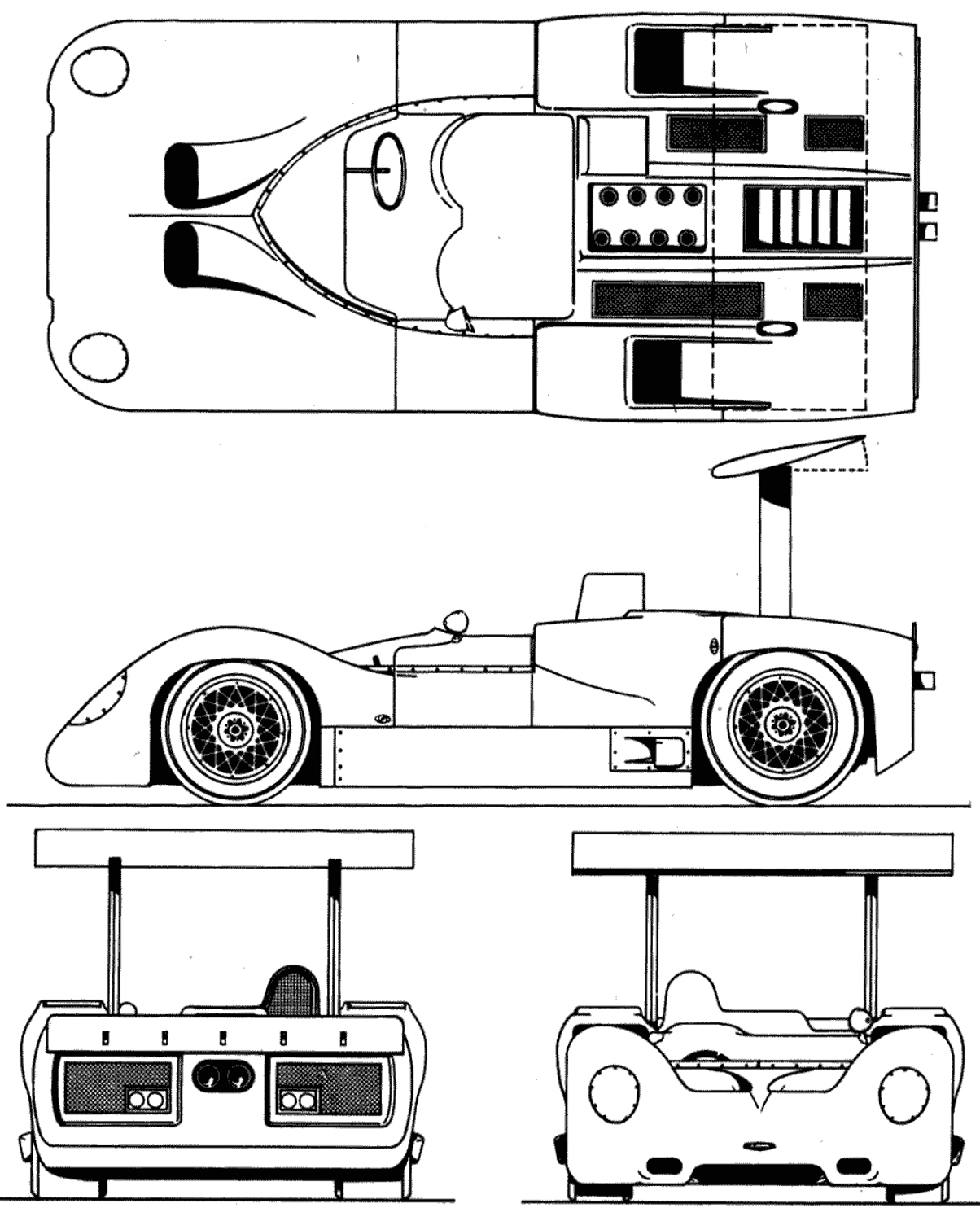

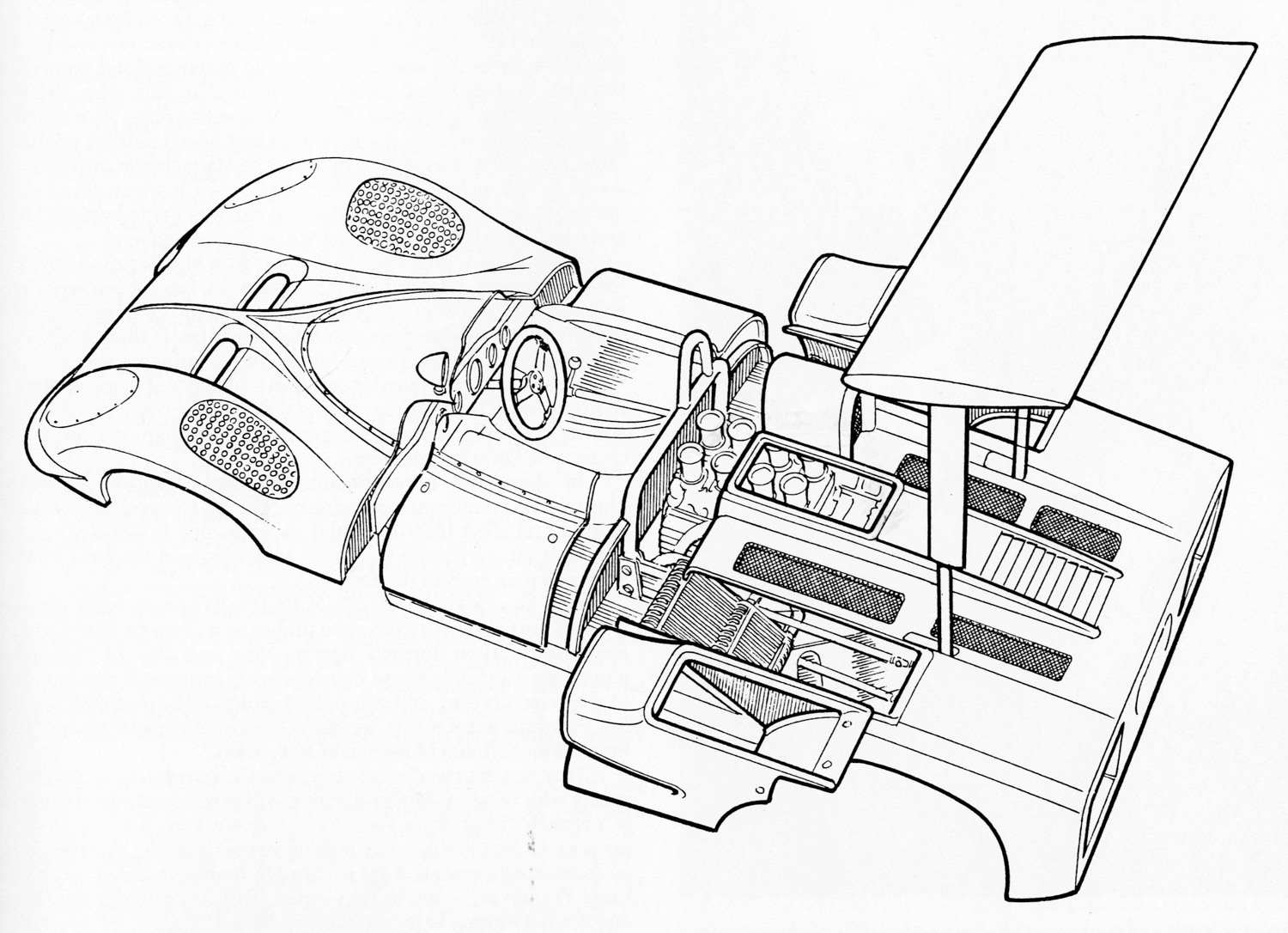

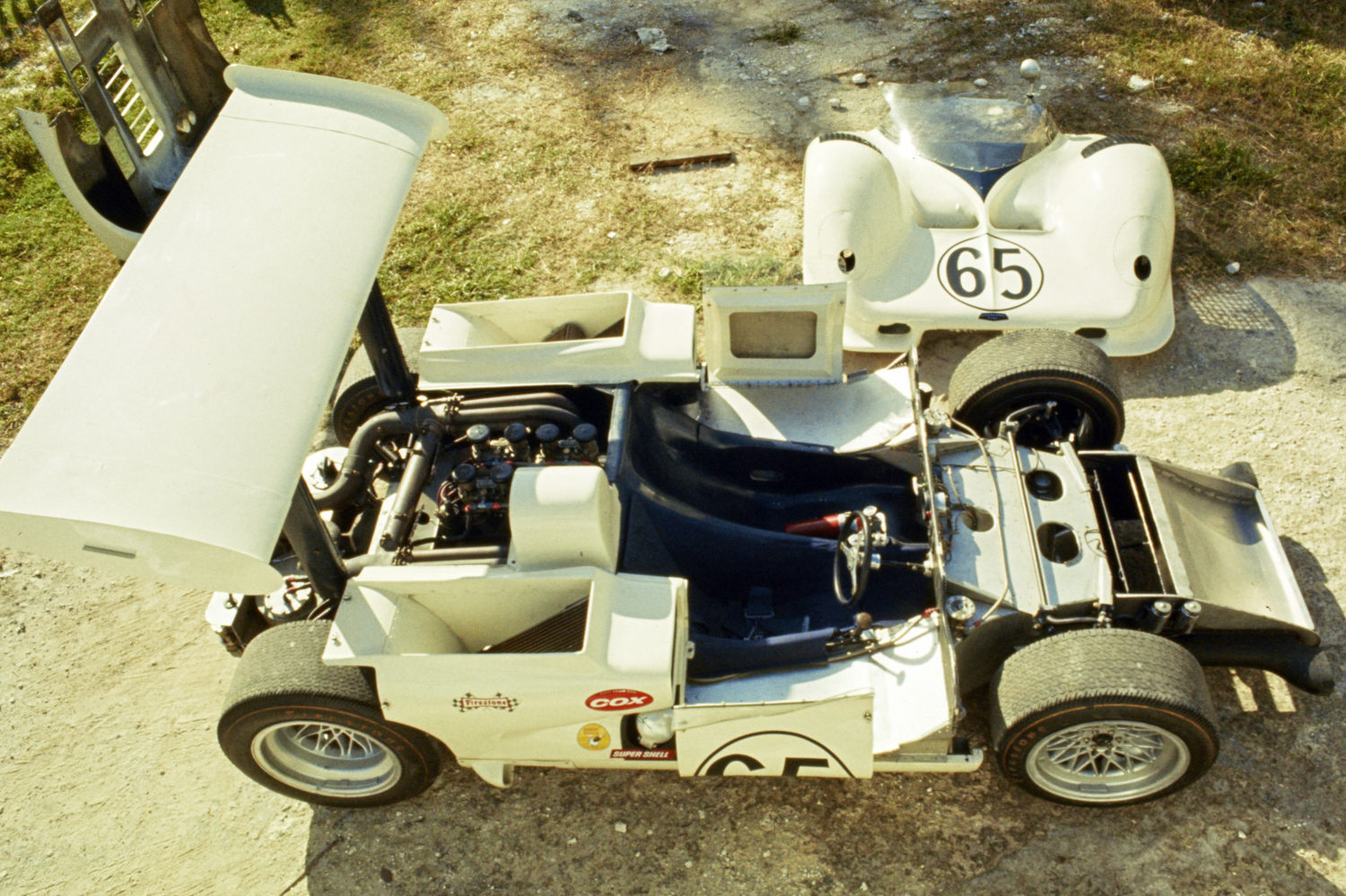

Meanwhile, back in Midland, the Chaparral crew, of which Franz Weis and Troy Rogers were stalwarts, were fabricating two 2E Chaparrals, completely new save for their 2C-type tubs and drive trains. They carried over the 2C suspension with its tubular front wishbones and anti-roll bars. Unlike the rest of the field they ran larger 16-inch wheels to have enough room for 12-inch disc brakes with ventilated Kelsey-Hayes rotors and Girling calipers. Firestone provided special tires for the team.

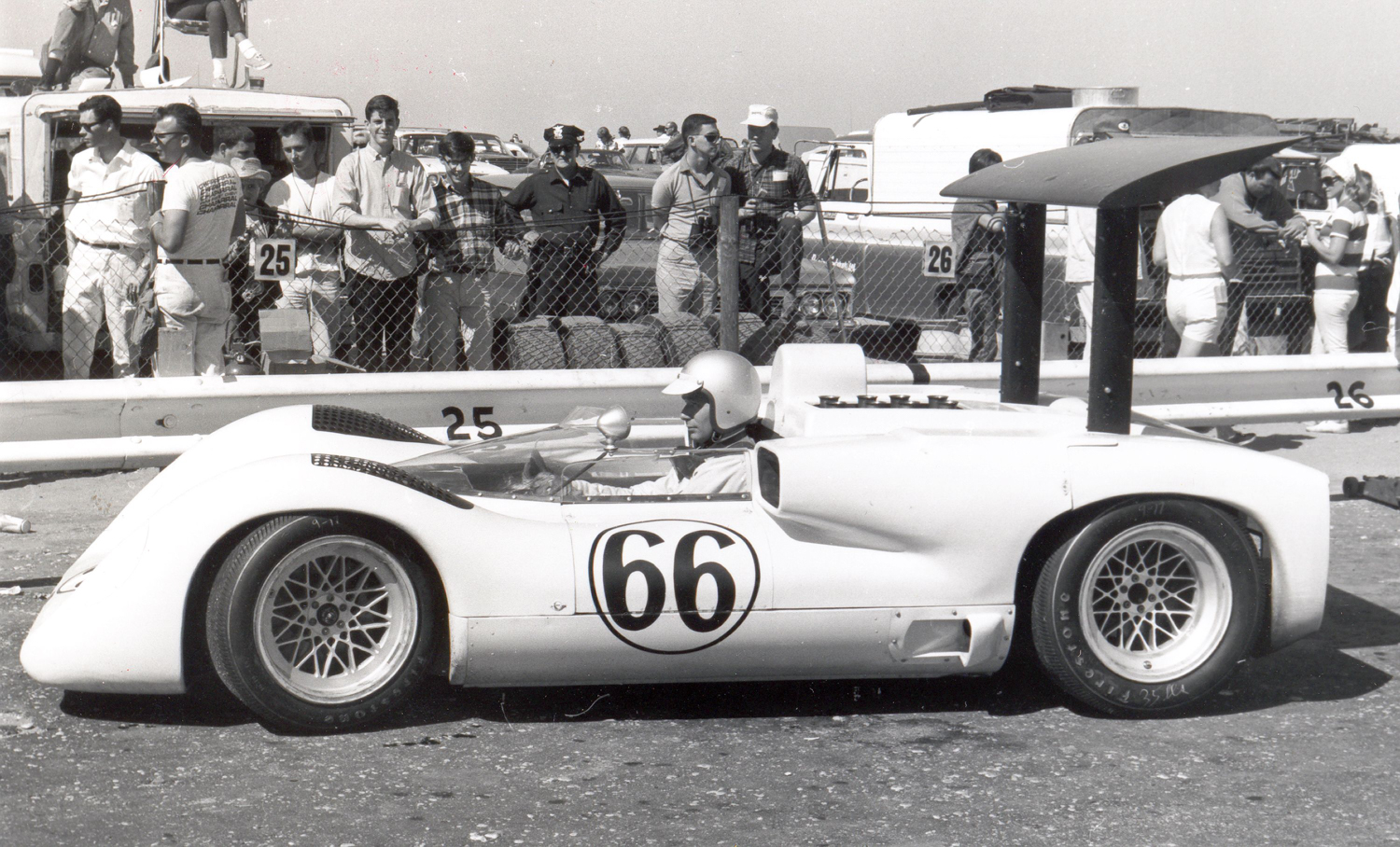

The design of the new 1966 Chaparrals was revolutionary, as my spies in Detroit had warned me, so I wasn’t as astonished as other railbirds when the two white cars were off-loaded from their usual pickup-towed trailers at Bridgehampton for the second Can-Am race of 1966 on September 18. “Wait until you see it,” I was greeted by friends at the Bridge. “It’s…it’s…it’s got a great big wing on the back!” Indeed it did.

Swiss racer-engineer Michael May is properly celebrated as the first to fit a proper downforce-generating wing to a racing car. He did so in 1956, he and a colleague designing and building an inverted aerofoil mounted on pylons where the downforce it generated would be best applied to the four wheels of his Porsche Type 550 Spyder. Moreover, he fitted a lever the driver could manipulate to have the wing at maximum downforce or minimum drag to choice. The rig proved so effective that Porsche lobbied successfully for its removal at both the Nürburgring and Monza.

An engineer, like Michael May—and one who associated with some good engineers at Chevrolet—a decade later Jim Hall was the man to tackle the wing idea properly. “I studied aerodynamics and thermodynamics in college,” Jim recalled. “And I learned to fly as a teenager, so I had experience with aeroplanes. All that went together for me. I can look at an aerofoil or get an aerofoil book and calculate the amount of force we’re going to get from this or that size wing, which is the way Chaparrals were built. We knew approximately what kind of force this wing was going to produce before we actually built it.”

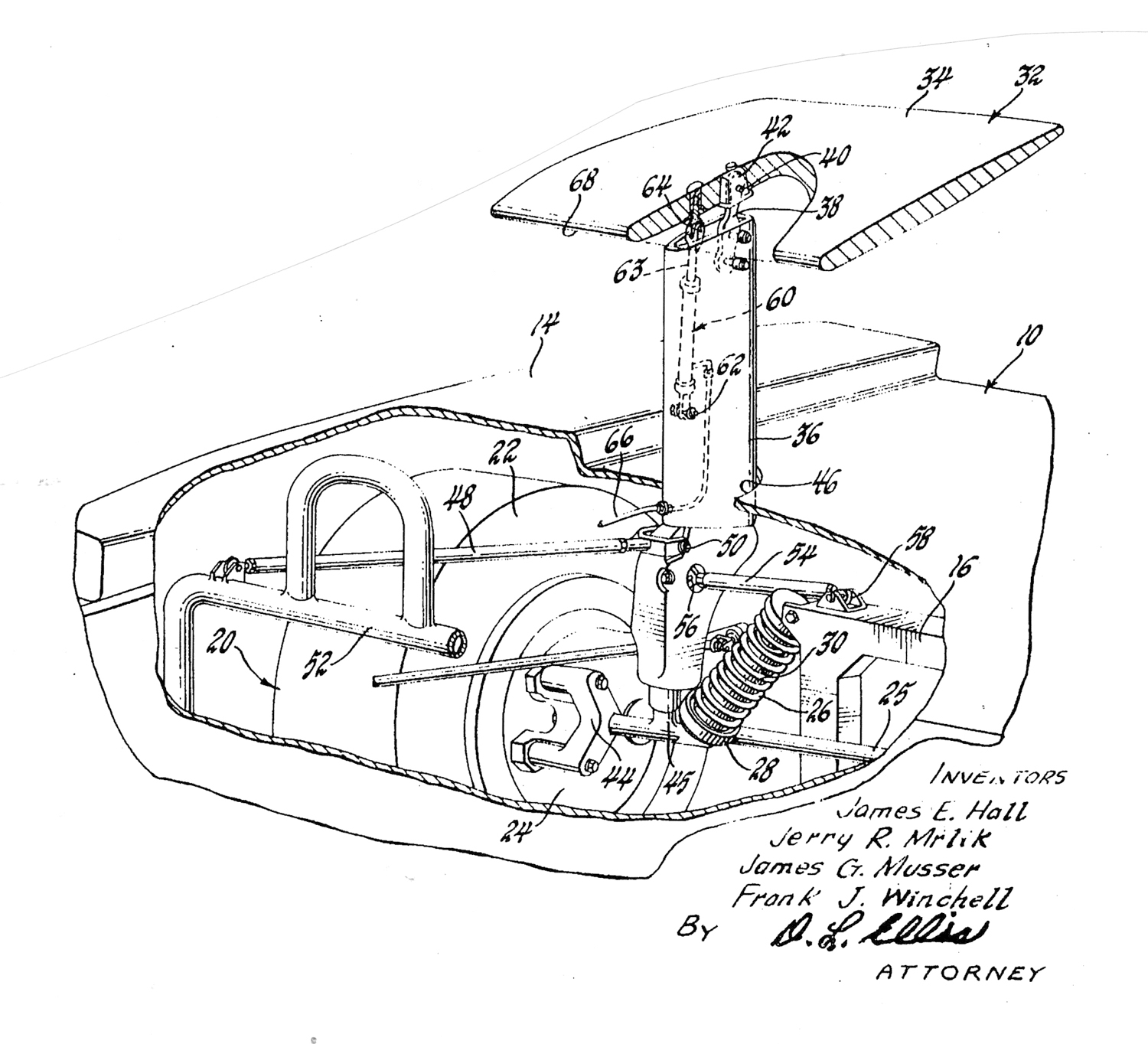

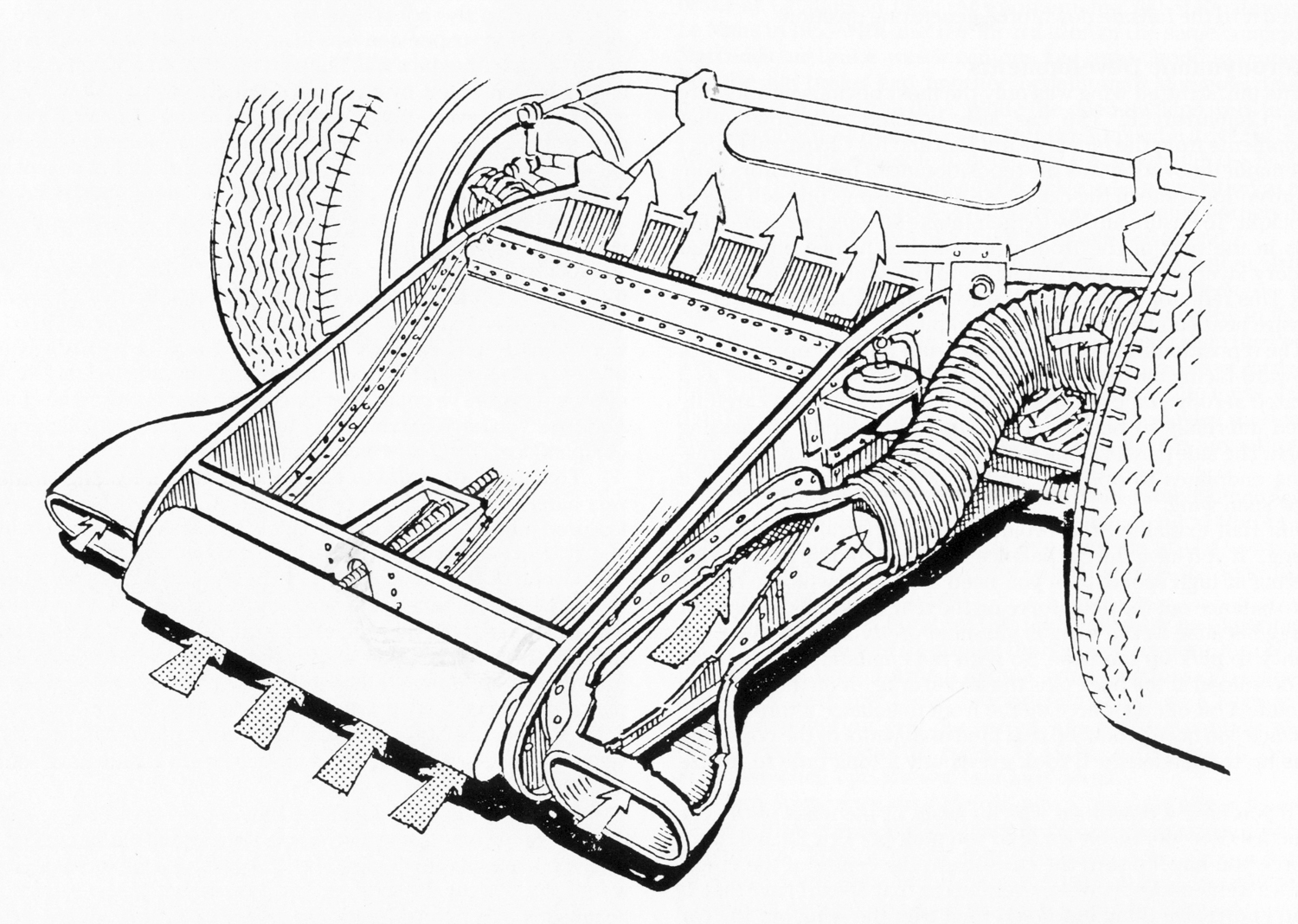

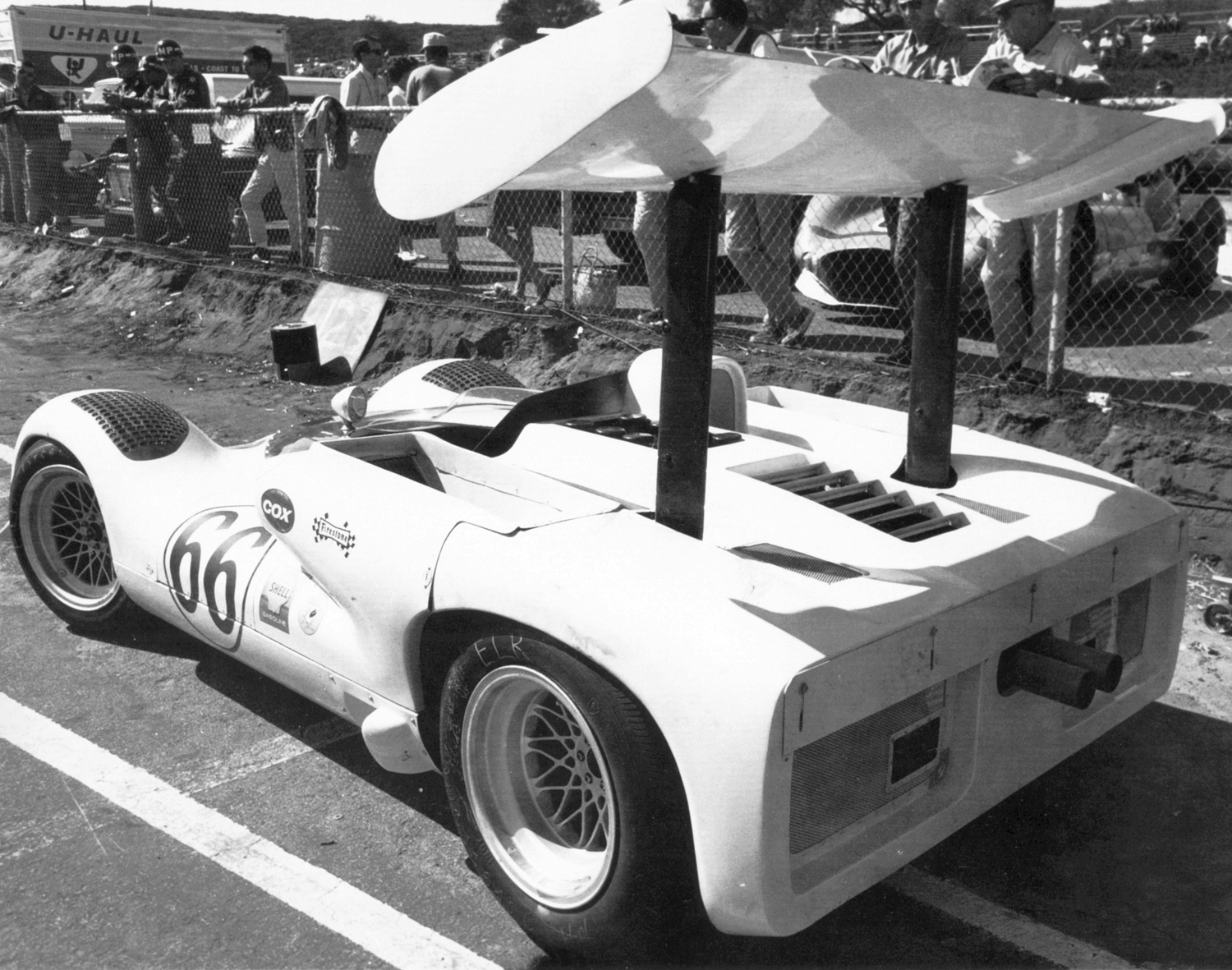

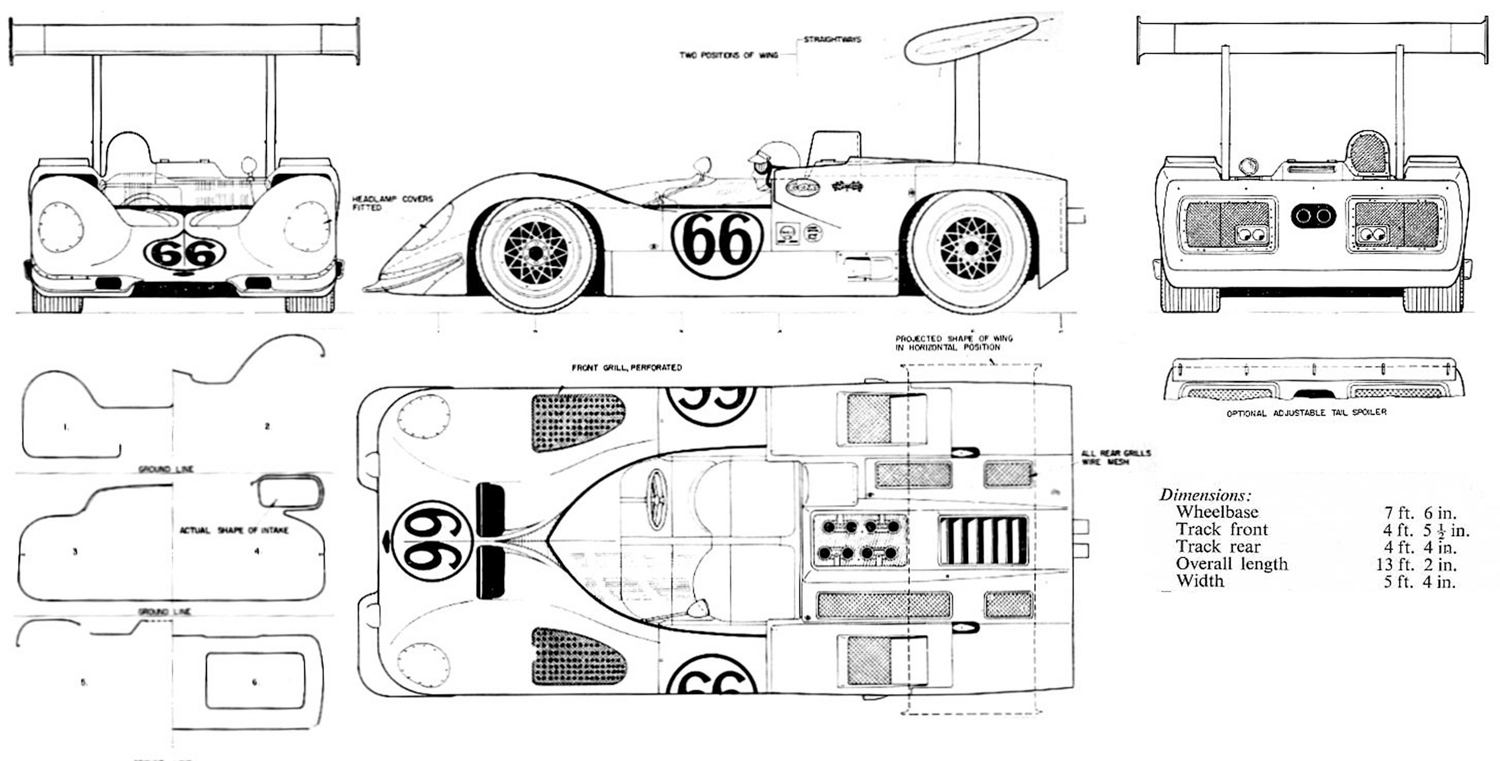

Working in close conjunction with his friends at Chevy, Hall’s breakthrough was in mounting the wing-carrying struts on the rear-wheel hub carriers so that their force was applied directly from the wing to the wheels and tires. This was done through tall pylons that held the wing well clear of the disturbances around the car’s airflow. Holding the pylons in place was a form of lateral Watt linkage and parallel trailing arms akin to those guiding the wheels.

Internally the aerofoil-shaped struts carried the hydraulic system that was used to change the angle of the wing while the car was moving. The wing was angled downward at an angle of 17 to18 degrees to generate 240 pounds of rear downforce at 100 mph in its default position, to help cornering, acceleration and braking. With a left-foot pedal the driver “feathered” it to four or five degrees below the horizontal—depending on the circuit—on straights to reduce drag. Applied for on March 22, 1967, the entire aerofoil system was patented in the names of James Hall, Jerry Mrlik, James Musser and Frank Winchell.

With this anchoring to the rear hubs, said Jim Hall, downforce is “not transmitted through the body and the spring system of the car. Now you can control the pitch angle of the car very much better because you don’t have to worry about this big force going into the bodywork. The other feature of it is that this is controllable by the driver in the cockpit. The wing’s center of pressure is forward of its pivot, so it always wants to turn away from where it’s hinged. If it’s in this position it wants to stay there.

“The driver has a pedal next to the brake pedal,” Hall continued. “When he gets out on the straight and he realizes that he’s not accelerating as fast as he’d like to, he just takes his foot over and pushes on the pedal. That trims the wing out and adjusts the front downforce. When he gets to the end of the straight and realizes that he’s going to stop, he takes his foot off that pedal and puts it on the brake. So it’s automatic. It’s fail-safe. You can’t go into the corner with the wing in the wrong position. We left-foot braked and right-foot accelerated.”

Adjusting the front downforce to balance that of the wing was the function of an air duct in the nose, where a radiator would normally be. Instead there was an air duct sweeping upward. When open, this duct produced an aerodynamic reaction that forced the car’s nose downward. Linked with the wing-controlling pedal was a flap that closed off the duct when the wing was feathered, reducing both downforce and drag.

So, where’s the radiator? As part of a major effort to shift weight to the rear driving wheels, two Harrison aluminium radiators were mounted athwart the engine, ahead of the front wheels, and sloping forward. Air entered them through forward-facing scoops and exited through large horizontal apertures above the radiators. Another benefit was greatly reduced cockpit temperature. Earlier Chaparral cockpits were so hot that late in their development a dedicated driver-cooling duct was installed.

Other measures to shift weight rearward included cylindrical tanks for engine oil and fuel at the extreme rear. A higher rearward weight bias meant better braking with the rear wheels still able to contribute during high-G racing stops. Overall the 2E weighed 1,365 pounds.

Shaping of all elements of the Chaparral 2E was masterful. It looked like no other racing car, a high-tech machine for speed created by some futuristic institute’s brilliant engineers. Its rear deck alone was a festival of fascinating panels, pipes, ducts and screens. This was a credit to Jim Hall, who said, “I shaped the bodies. I’m the guy that went out there and shaped them. Most of the shapes on Chaparrals were my sculpture. I’d come back after dinner and go to work on the clay and make the changes that I thought necessary. The guys would come back in the morning and smooth it all out, make it look okay. And then I’d critique it and do it again.”

“Overall,” wrote Chaparral chroniclers Richard Falconer and Doug Nye, “the new Chaparral 2E’s body gloriously emphasized the project’s painstakingly pragmatic approach not only to the science of aerodynamics but also to the practicality of covering the most with the least. The panels did nothing more than hug the mechanical components housed within: the header tank became part of the headrest, the windshield was sharply vee’d in sympathy with the twin outlets for the nose venturi tunnel, and so on. The Chaparral 2E breathed pure function with a futuristic sense of style never forgotten.”

Delayed in his testing routine by his big European endurance effort, Hall hadn’t been able to test the 2E as thoroughly as he had wished. The fast, bumpy Bridgehampton track finished the job for him. A bolt working its way out of the Watt linkage on Phil Hill’s car departed in practice, sending him off the track. Phil took over Jim’s car for the race—and had trouble with the hydraulic wing-trimming control and sticking throttles. From second place he fell to fourth at the finish.

Hill set the fastest lap at Bridgehampton and Jim Hall did the same at Mosport before retiring. There, Phil Hill was delayed by a bumping incident but managed to hold onto second place. In their third outing at Laguna Seca, the 2Es dominated both practice and the race. New longer wings with endplates were fitted as the team gained confidence in the radical system, allowing the white cars to soar up and down the hilly California course with arrogant ease.

“The 2Es finally fulfilled their potential at Laguna Seca,’ said Hill, ‘with Jim setting a new lap record in qualifying. We were 1-2 (Hill-Hall) in the first heat, and 2-3 (ditto) in the second, giving me the overall win.’

Powered by special aluminium-block 327-cubic-inch Chevy engines with Chevrolet’s homemade Weber-type carburetors, the Chaparrals had between 420 and 450 bhp at 6,800 rpm and torque curves tailored to the torque converter characteristics. This was not quite enough horsepower to put on a strong show at the fast Riverside track—the only Can-Am they entered that year without collecting the fastest race lap. Hall was second there.

They looked stronger in the 1966 Can-Am finale at Stardust Raceway, Las Vegas, where Hill and Hall shared the front row of the grid, the latter setting a new track record. “Soon into the race,” Phil related, “the rod that actuated the wing on Hall’s car broke and the wing began to flap up and down. He retired, and not long after the same thing happened to my car. That was one thing about Chaparrals: no one could ever complain he got the lesser car because they were identical. To be safe they removed my wing, but now the handling was unbelievably awful, oversteering so badly I could hardly drive the car. I skated home to seventh. So ended the race and my Can-Am career. I can’t imagine a more interesting car in which to do it.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZw-CT9gl0U

Hill and Hall finished the Can-Am season only fourth and fifth on points but their cars had clearly been the quickest. The quiet precision of the Chaparral team operation, developed through the successful USRRC seasons, was still evident. But Hall admitted that “in designing for aerodynamic loads on remote-mounted wings nobody gave enough safety factor for the inertia loads that came into the support strut from the acceleration from the wheel bumps. That’s a high cyclical load.”

Jim Hall summed up the 2E story as follows: “In 1966, we decided to build a car that embodied everything we’d learned about aerodynamics up to that point and maybe a little bit about vehicle dynamics too. So we did a lot of things with 2E that are different from the earlier cars. It was very successful in the sense that it was fast and easy to set up when we went to the race track. I think it was a really versatile good racecar. It was not very reliable. And we didn’t win many races. So from that standpoint it wasn’t as good.”

Asked what he would do differently, Hall said, “I would have slowed down the pace of our development, given myself time to make sure I had a reliable product. In 1966, when we ran the 2E, that dramatic moment in aerodynamics, it wasn’t ready. If we had worked on it we would have won almost every race. In ’66 and ’67, GM put a lot of pressure on me to run an alloy big-block. I had 11 engine failures in one season. So my career—our career at Chaparral, I should say—was marred by me jumping in too fast, trying to do things outside our capabilities in manpower and time.”

Of the 2E he added, “We probably introduced it a little too early. Should’ve had more testing on it. But that’s the way we did things. We were a small team. We built the cars in the winter and took them racing in the summer. That was it. We were the small team from Texas that rolled in with a pickup and a trailer and ran our races and left. And it was fun.”