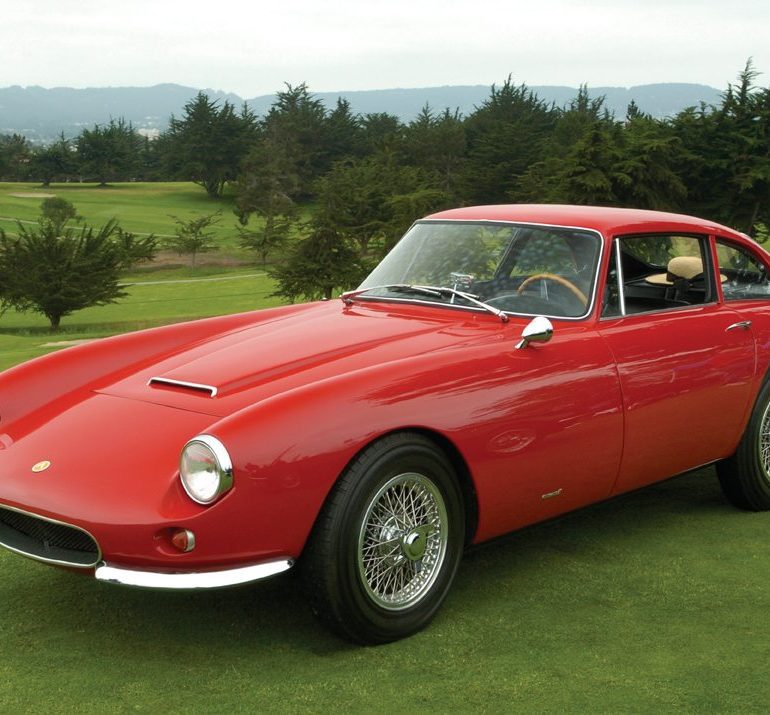

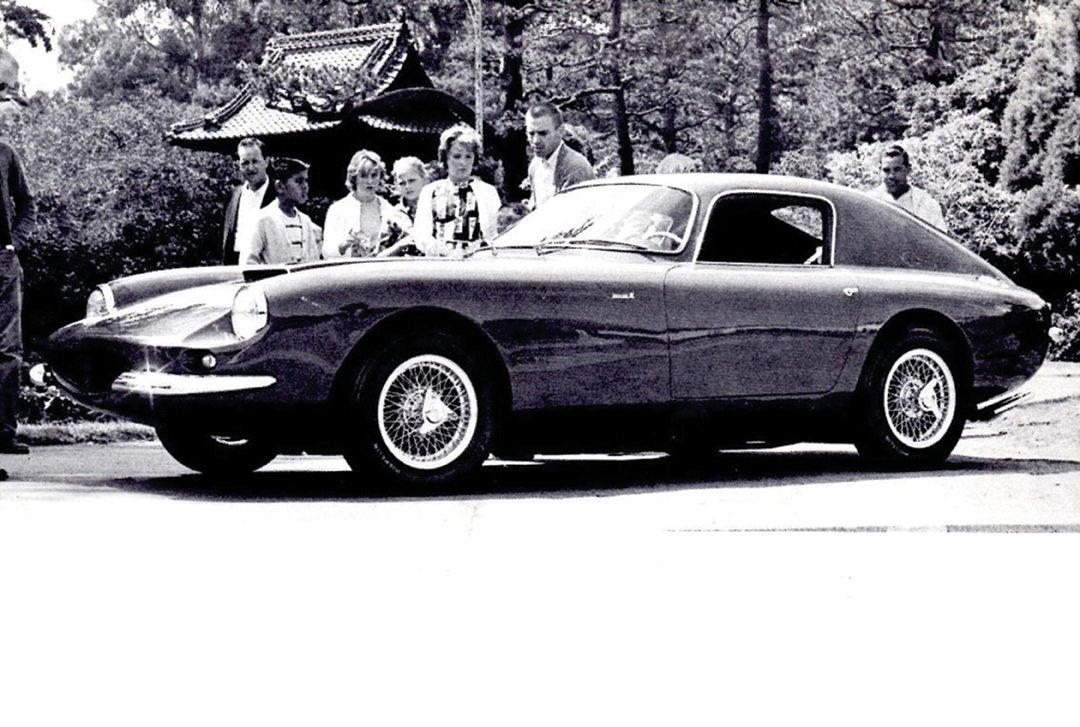

The Apollo GT was the brainchild of engineer Milt Brown and his partner Newt Davis. The youthful entrepreneurs envisioned a sports car with American reliability and Italian inspired design. The Apollo GT took shape as Frank Reisner, founder of “Intermeccanica,” became the coachbuilder. Brown enlisted designer Ron Plescia to sketch initial concepts for Intermeccanica to build in aluminum over the Milt Brown designed chassis. The first prototype was deemed too long in front and rear visibility was limited. Reisner called on former Bertone designer Franco Scaglione to refine the design, and the first cars went into production in 1963 as the Apollo 3500GT. Intermeccanica produced all Apollos in hand-formed steel, fabricated in Turin, and shipped to Oakland, California, where the drivetrains were installed and prepared for display at Brown’s dealership, International Motorcars of Oakland.

The dimensions are similar to a Jaguar XKE and this should come as no surprise given Brown and Plescia used the XKE for reference. However, this is where we see a range of design interpretation as the Apollo became far more muscular and upright than the XKE, due in part to the fully exposed wheels. The production Apollo, however stores most of its visual energy high in the full fenders and tall shoulders. The earliest version of the Plescia design shows a more rounded roofline, a smaller rear window, and no quarter glass. In the production rear design, we see hints of the XKE in the tail light and bumper treatment, but with a more rigid architecture. The best view of the Apollo is the front ¾, looking down on the hood leading up to the gently sweeping windscreen. The hood scoop is sculpted all the way up to the forward edge of the hood line, further elongating the car and echoing the front fenders beautifully. The most challenging part of the design was to incorporate the quarter glass into the design. The introduction of a solid B-post and quarter glass, interrupted the roof line. Molded as low-cost flat pieces, the quarter side glass lacked the contour and shaping that could have improved the shape of the upper body. These compromises forced the roof line to be taller, and limited the amount of tumble-home (lean-in to the upper roof). Tall roof, large muscular shouldered fenders, and flat glass somewhat compromised the production design of the Apollo. Restoration of Apollos has always been challenging due to lack of parts and its unique body, but values have increased enough to warrant complete restorations. My suggestion for anyone restoring an Apollo is to not “over-tire” the car. The original wheel openings tuck into the upper fenders and cause the tires to bulge outside the fender line. For some reason, this effect is greatly reduced in the convertible. Though I have never measured these, I suspect the fenders on the convertible are slightly more rounded and flared outward to adjust for this effect.

Rare when built, these coachbuilt cars are coveted today by collectors and enthusiasts internationally. The Apollo GT exhibits all the wonderful features of the most desirable European cars of the same era, coupled with American power and the unique “start-up” bravado of two young entrepreneurs, dreaming of a GT sporting future.