One of my favorite telephone conversations of 2007 was with 1950s Bonneville-racing-legend Denny Larsen. For those of you unfamiliar, Larsen built the Maybee Drilling Special that raced across the salt at 203.105 mph in 1953, becoming the world’s fastest sports car. Larsen’s team also made history in 1957 with a Sorrell-bodied, D-Modified sports car that was a record breaker at 178.068 mph. Now, more than half a century later, Denny is instantly friendly, happy to talk your ear off about all things racing and nonracing. Our three-hour “tour de phone” included tales of everything from his end-over-end airplane crash to the never-finished Bonneville car stored in his Arizona barn.

After about two hours, I was able to gently steer the conversation toward the original impetus for my call. I was researching the history of one of my own racing cars, built by Bob Sorrell in the 1950s on a Chuck Manning chassis. As Larsen and Sorrell had been friends (and since Larsen’s car set a ’57 Bonneville record in a Sorrell SR-100), I had hoped he might be able to shed some light on the history of my car. No such luck, he didn’t remember anything.

Fast forward eight months, when I received a telephone call from Tampa- based Geoff Hacker, a voracious collector of all automotive things unusual…and sometimes beautiful. Hacker apparently had had his own three-hour conversation with Larsen and was potentially interested in acquiring the never-finished salt car in the barn…the car with no history, the one I had been so shrewd not to waste any time inquiring about.

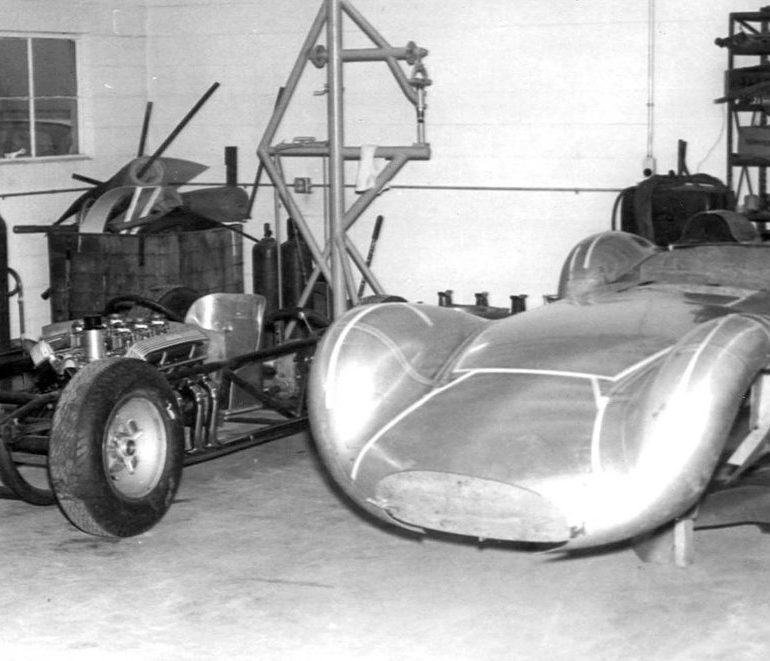

Emailed photos followed, and the car was indeed unfinished. But it was well constructed and quite attractive, and I was starting to feel not quite shrewd. Hacker made a deal with Larsen, bought the car, and then he did something that I can never forgive. He emailed the photos to one of my best car buddies, automotive historian Harold Pace who immediately uttered five excruciatingly painful words, “I’ve seen this car before.” Without skipping a beat, Pace calmly walked across his office, plucked Allan Girdler’s American Road Race Specials from a shelf, and flipped to page 138. There, he reacquainted himself (and soon me) with three photographs of a 1960 project, built for racing-legend Bill Stroppe by racing-legend Don Edmunds (Rookie of the Year at the 1957 Indianapolis 500). It turns out the car wasn’t originally built with a hardtop. And it was conceived as a road racer not a car to run at Bonneville.… That had been Larsen’s idea, ever since he added the roof after dragging the car from Dean Moon’s shop many, many moons ago.

And while Edmunds’s recollection of the end of the story, how the car wound up at Moon’s shop, is somewhat vague, his memory of the car’s beginning is crystal clear. “Stroppe wanted me to build him a sports car. At first, I started working on the project as an after-hours part-time deal, while I was working for Bill Devin.

“Later, I quit Devin and started working for Stroppe, full time. As a driver, Stroppe was very strong in the sports car races. This project was his idea of ‘now we’re going to build our own sports car with this big Lincoln engine in it,’ which obviously was a mistake. Looking back, the car was going to be a truck. It was basically an Indy Roadster as a sports car. It wasn’t going to be a competitive car, but Stroppe would have driven the hell out of it, if it ever got finished.”

According to Edmunds, “The Bear Cage is an almost unknown name for the car. But it was named after Stroppe. The guy was a hairy beast and some of the traveling crew who worked for him referred to him as ‘the bear.’ I started to build the car about the time the Birdcage Maserati was around, and Vern Houle who was the engine man at Stroppe’s started calling it the Bear Cage.”

Edmunds built the car on a ladder frame from large round tubes with live axles at both ends. A unique feature of the car’s design was the use of a Watts link for each axle. In keeping with the overall theme, the car had a sprinter steering wheel and seating position as well as a Halibrand quick-change unit. For power, Stroppe chose a Lincoln V-8 unit, which Edmunds offset to the extreme left. Finally, the car was skinned in a curvaceous one-off, alloy-roadster body built by California Metal Shaping from a buck of Edmunds creation.

Edmunds recalls that he stopped working on the project when it was a roller with a body: “The Bear Cage deal just kind of faded away, as Stroppe got me involved in other projects. It’s funny! I never even knew when it left.” At some point, Edmunds learned that the car went to Moon’s shop but that’s where the story ended. Other than the Road & Track file photos (these photos were never actually published in the magazine) that Girdler found while researching his book, no other photos or records have been seen, and the car had gone missing, unknown, forgotten…until Hacker showed up and Pace did his magic.

Hacker has brought the car back to his Florida home and feels privileged to be the custodian of this most-intriguing, never-raced racecar. According to Hacker, “I’m planning on restoring the Bear Cage to honor the racing legends associated with it. It’s what the car and these great men deserve.”