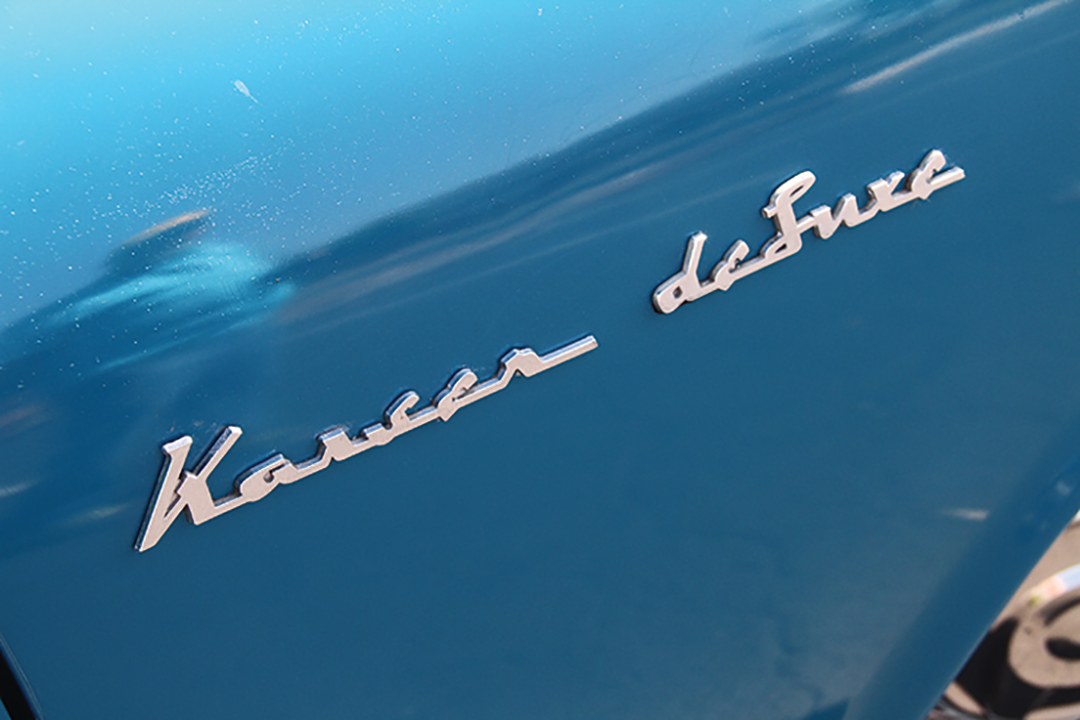

I spotted Phil Jelinek’s beautiful ’53 Kaiser Traveler Deluxe from across the Huntington Beach Concours show field. That is because this elegant, sporty looking automobile is even more distinctive today than it was when it was first introduced nearly 70 years ago. Its elegant design stands out when positioned next to other cars of its era, and is all the more unique when compared to the homogenous looking doorstops we drive today.

Just sitting in a Kaiser was a revelation for me. I grew up around—and in—early ’50s cars and I remember all too well the rather conservatively styled, stolid, heavy vehicles of that day. Most circa-1953 autos had frumpy bodies, smallish windows, thick posts and chromey, Wurlitzer-juke-box-looking dashes.

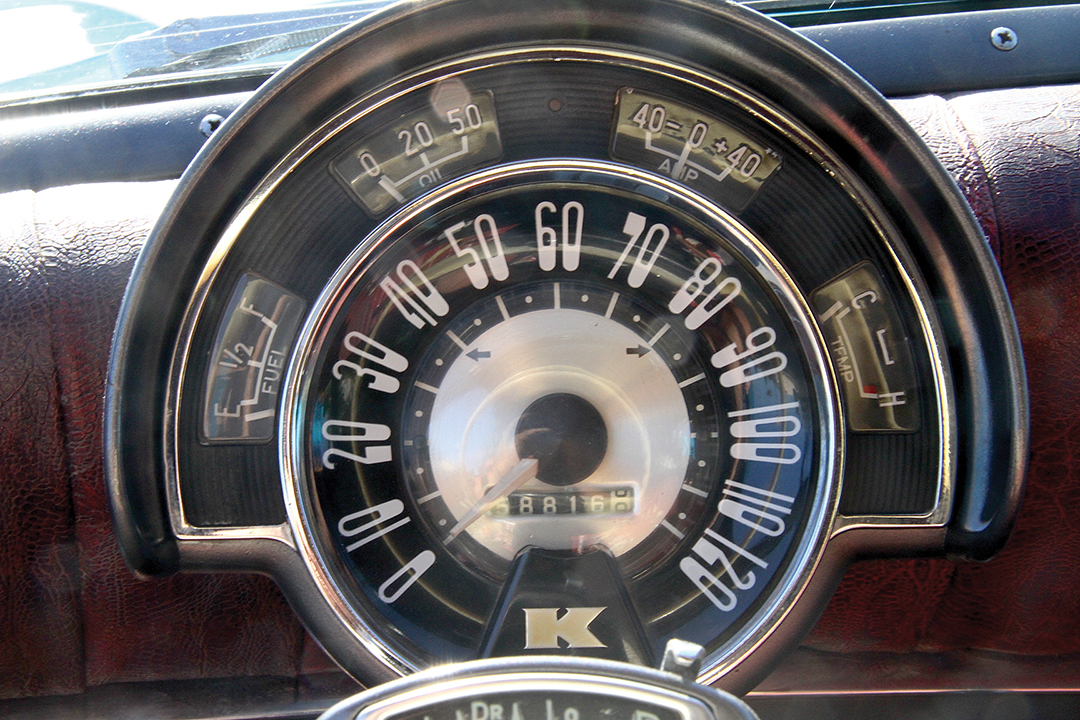

The ’53 Kaiser is different. Its instruments are clustered nicely in one, easy-to-read round unit. Its dash is padded for safety and hooded to prevent glare. Its windows and windshield are huge, and its A and B pillars are narrow and discreet, making for great visibility and eliminating blind spots. The interior room of the car is ample in every way, and sumptuously appointed.

I make sure the column-mounted shift lever is in neutral and twist the key. The 226-cu.in. Continental six starts almost instantly, and after a brief moment settles into a nearly silent purr. If you haven’t experienced the smooth solitude of an old side-valve six for a while, you have probably forgotten just how vibration-free and quiet they are.

Jelinek’s Traveler is equipped with the optional Hydramatic transmission purchased from General Motors, which was not unique. Other independents such as Hudson, Nash, Willys and even Lincoln also sported Hydramatics at the time. This was due to the high cost of developing proprietary automatics of their own.

I am surprised at how light the steering is. Ditto the brakes. Jelinek’s Traveler has power steering but not power brakes, though it doesn’t need them. Granted, drum brakes can fade when overheated, but if they are properly engineered, they are fine for normal use. Of course, they weren’t made to contend with a ditzy kid jumping in front of you suddenly and braking while texting on a cell phone.

In 1953, Ford’s famous flathead V8 only made 100 horsepower, and the company’s little six only pumped out 95. Plymouth’s flathead-six developed a sedate 97 horsepower. And Chevrolet’s 235-cu.in. Blue Flame six—offered in combination with their Powerglide transmission— made 105 horsepower, but their standard 216 generated a mere 92 ponies.

We cruise out into the mid-’50s suburb of Garden Grove, California, and I am taken aback at how well the Kaiser handles, rides and stops. Its interior is very comfortable and roomy, as well. The car somehow feels lighter and more responsive than any of the low-priced three with which the Kaiser was intended to compete. That’s probably because Kaiser used an extremely light 200-pound frame and a rather rigid body that sat low on its chassis, though the Traveler’s chassis is somewhat heavier in order to carry loads.

Back then, Kaiser boasted that its 1953 Deluxe was America’s first Safety First car thanks to its padded dash, pop-out windshield and heavily padded seats. (Many contemporary cars had the windshield installed from inside the car, and as a result it would tend to shatter in, onto the passengers, in a crash.) Sadly, however, safety didn’t sell Kaisers, nor did it help the contemporary Tucker or even Ford in the late ’50s.

Kaiser introduced the Traveler, as well as the Frazer Vagabond, which was an upscale version of the Kaiser, in the 1949 model year as a stylish alternative to the ever-popular station wagons of the time. It was industrial-colossus-turned-automaker Henry J Kaiser’s own idea, and it was a good one. The Traveler looked like the rest of Kaiser’s offerings, but its back seat folded flat, creating a large, well appointed cargo area with lovely natural oak runners to protect the paint

Even the spare tire is recessed below the trunk floor and is accessed through a hatch. The fuel tank is specially contoured and positioned in the driver’s side rear quarter panel to allow for this. Kaiser referred to their Traveler as a utility vehicle, and I remember as a kid seeing an ad in Popular Mechanics touting a canvas after-market tent-like assembly that attached over the upraised hatch of the Traveler that allowed for comfortable camping.

Phil was a mechanic for many years, and eventually became an auto shop teacher, so he knew very well that Kaiser’s careful engineering, though not unique or cutting edge, involved a very good combination of components. Kaiser’s engine was solid and dependable, the Hydramatic transmission had been around for a decade by that time, and its Dana rear end was excellent.

On the road, with the rear seat folded down so the trunk and rear passenger compartment are one common space, there is a bit more road noise, and there are some spring rattles, much like what one hears with a conventional station wagon. But you can haul home a heap of building materials, or enough garden mulch to do the extensive lawns of a ’50s era ranch house, in the cargo compartment behind the front seat.

So what killed Kaiser? It certainly wasn’t because they made bad cars—and contrary to popular belief—I don’t think it was primarily because they never offered a V8, although they had developed a modern 288-cu.in. overhead valve prototype that they chose not to use.

Kaiser’s biggest problem was that it was the new kid on the block and had a lot to prove. Just making a car that was as good as, or even a bit better than, any of the low-priced three wasn’t enough. There was still the need for a massive marketing arm to get the word out, and that needed to include a dealership network that came close to equaling that of the other major players. And, of course, most well-established, experienced dealers were not going to gamble on switching to an untried product from a new manufacturer with somewhat tenuous connections to the industry.

To begin with, the company was under-financed. Although Joseph Frazer, a veteran of top management at Chrysler, Willys and Graham Paige, and Henry Kaiser’s partner in the venture, had long experience in the auto industry and had been a leading light at Chrysler, even he didn’t realize the immense amount of capital that would be required to sustain their new company.

Frazer did know the industry though, and surmised that the company needed to cut back production in 1949, as the market was becoming sated. Unfortunately, Henry would have none of it. As a result, dealers wound up with a surplus of last year’s models, and the partners parted ways, after which the Frazer marque was dropped in 1951, even though it sold reasonably well as the result of a restyle in 1950.

He reasoned quite correctly, early in the war, that there would be a big demand for new automobiles when hostilities ended, and he wanted to get in on the profits. Though he didn’t know much about cars they had always captivated him, and he was brilliant at industrial management.

Kaiser wanted to build a car for the average returning G.I. Joe, to compete with the low-priced three. He also had some visionary ideas that he thought were good and he wanted to try them out. At that point, in 1945, he and Joseph Frazer became partners and started Kaiser Frazer, with Frazer as president and Kaiser as general manager.

At first, both Kaiser and Frazer, its upscale companion make, sold well because there was tremendous pent up demand for cars, and they were the first all-new ones; unlike the warmed over pre-war models of the big three. As a result Kaiser-Frazer did very well in 1947 and ’48, making a healthy profit and putting them ninth in sales in the industry ahead of all the other independents.

After that, a stock underwriting double-cross by a trusted underwriter put them deeper into the hole, with Kaiser having to bail out the company himself. Another mistake was Kaiser’s new compact offering that came out in 1950, dubbed the Henry J. It was a small car intended to compete with Rambler, but it was not nearly as refined and well thought out. It was a nice looking little car, but at first it had no trunk lid, no openable rear windows, and was generally cheap and spartan, even though it sold for within a few dollars of the Rambler and the Studebaker Champion.

Kaiser was no different, and merged with Willys Overland in 1953. That actually turned out to be one of the company’s best decisions in the long run. Willys continued to produce Jeeps until the brand was finally sold to American Motors in 1970, and then to Chrysler, which kept it going after that.

After the last American-built Kaiser was produced in 1954, the company assembled Kaiser’s big sedans as the Kaiser Carabela in Argentina until 1962, which incidentally was Spanish for caravel, a type of fast, sailing ship. Kaiser Frazer and Willys built some great cars, but were crushed along with the rest of the independents by the giants of the industry, and that was unfortunate because competition from the independents kept the big three on their toes.

After our test drive and photo shoot, Phil Jelinek, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of the company and its history, made my job easy by showing me all of his records, notes and collected brochures on the car. It was a great way to wind up a fun afternoon of driving a significant part of America’s automotive history.

Specifications

Price $2,619 • Production est. 946 • Engine Inline six • Displacement 226.2 cubic inches • Bore/Stroke 3 5/16 inches x 4 3/8 inches • Horsepower 118 @ 3,600 rpm • Torque 200 lbs-ft @ 1,800 rpm • Comp. ratio 7.3:1 • Fuel system Carter WCD two-barrel • Transmission Optional GM Hydramatic • Rear axle Hypoid semi-floating, open drive • Steering Monroe power steering • Brakes four-wheel internal hydraulic, drum type • Chassis/Body Construction: Body on frame • Suspension Front–Independent solid axle Double A-arm coil springs Rear– Solid axle semi-eliptic leaf springs • Shock absorbers Direct-acting aircraft type • Tires 7.50/15 • Weights and measures: Traveler four door sedan: 3,115 lbs • Wheelbase 118.5 inches • Length 210.4 inches• Track front 58 inches • Track rear 59 inches • Overall height 60 inches