Adults dream of regaining their youth. Children yearn to do grown-up things. This is the nature of our existence. As the location of the fountain of youth remains enigmatic, we are all on an inescapable collision course with wrinkly, stiff and forgetful. On the other hand, children have always found a way to emulate their elders. Dress up like mommy and daddy; wheel the (plastic) baby in the stroller; and create gourmet concoctions in the Easy Bake Oven.

Whereas these make-believe activities nurture the pediatric imagination, the holy grail of all grownup activities remains the independence that comes with driving a car. This burning desire, no doubt, led to the construction of the first four-wheeled “child-mobile” whose date of assemblage will never be known.

However, the roots of the very first soap box racecars can be specifically traced to Dayton, Ohio, in the early 1930s. At that time, vehicles were being built from wooden shipping containers for soap. Myron Scott was a photojournalist for the Dayton Daily News and organized two soap box races in the summer of 1933. The first race involved only 18 cars and garnered little to no attention. The second race was heavily advertised and attracted more than 360 children and almost 40,000 spectators; Scott knew he had something very special.

With huge financial backing from Chevrolet as the national sponsor, heavy local newspaper involvement across the country, and our nation needing something to believe in post-depression, the Soap Box Derby captured the imagination of an entire generation. The race was moved from Dayton to Akron in 1935, and shortly thereafter a purpose-built track for the All-American Soap Box Derby was constructed. Unlike almost any other event, The Derby has touched and improved the lives of hundreds of thousands of children and adults.

One such individual was Joe Lunn, who built his soap box racer starting with a goat cart. Lunn came from a farming family living in the small town of Thomasville, Georgia. His parents weren’t together and he grew up poor in a falling down shotgun house without electricity or plumbing. Lunn said, “In the summer of 1952,Z my mom’s brother, my uncle Arthur Hudson, came to visit us. He noticed the cart I’d built for my pet goat to pull around and suggested I enter it in the Soap Box Derby. I’d never heard of The Derby and I don’t think anyone else in Thomasville had either. So my uncle invited me and the cart to his home in Columbus (Georgia) for the summer. I had to redesign the goat cart to meet Derby rules, and my car was anything but good looking. The car did have a novel wooden suspension of my own design, and I was pretty proud of that. I was having fun with my uncle and really wasn’t expecting much. Then I won the Columbus race.”

Next Lunn was invited to the championship race in Akron. This was a huge event for a boy from a town scarcely on the map. The crowds were enormous and celebrities such as Jimmy Stewart, Edgar Bergan (with Charlie McCarthy), and Joe E. Brown were part of the spectacle. Lunn recalls, “There was a Soap Box Derby camp for a few days before the race. My family could never afford to send me to something like that, and I got to experience a whole new world of excitement. Then the race rolled around and I knew that would be the end of the fun. My car had been fast enough for Columbus, but in Akron I was totally outclassed. I was just sitting on the top of the hill looking at all the other competitors prepping their wheels, tires and bearings. My car was just kind of cobbled together from a goat cart. There was a kid from Germany working on this car that had a surface finish like a solid piece of glass. I thought, oh well, this has been fun.”

From there things only went downhill (pun intended, thank you). In the first heat Lunn’s steering cable ruptured. His car veered violently to the right with no way for Lunn to control its trajectory. Lunn T-boned the large railing on the right side of the track, splitting his car in the midline front to back. Lunn said, “It was a nasty, brutal crash and I sustained a laceration on my chest. I still have the scars to prove it. I also hit my head and was a bit dazed. I was pretty well battered and covered in blood. My car was destroyed. It had been a wonderful journey, but I now knew it was over.”

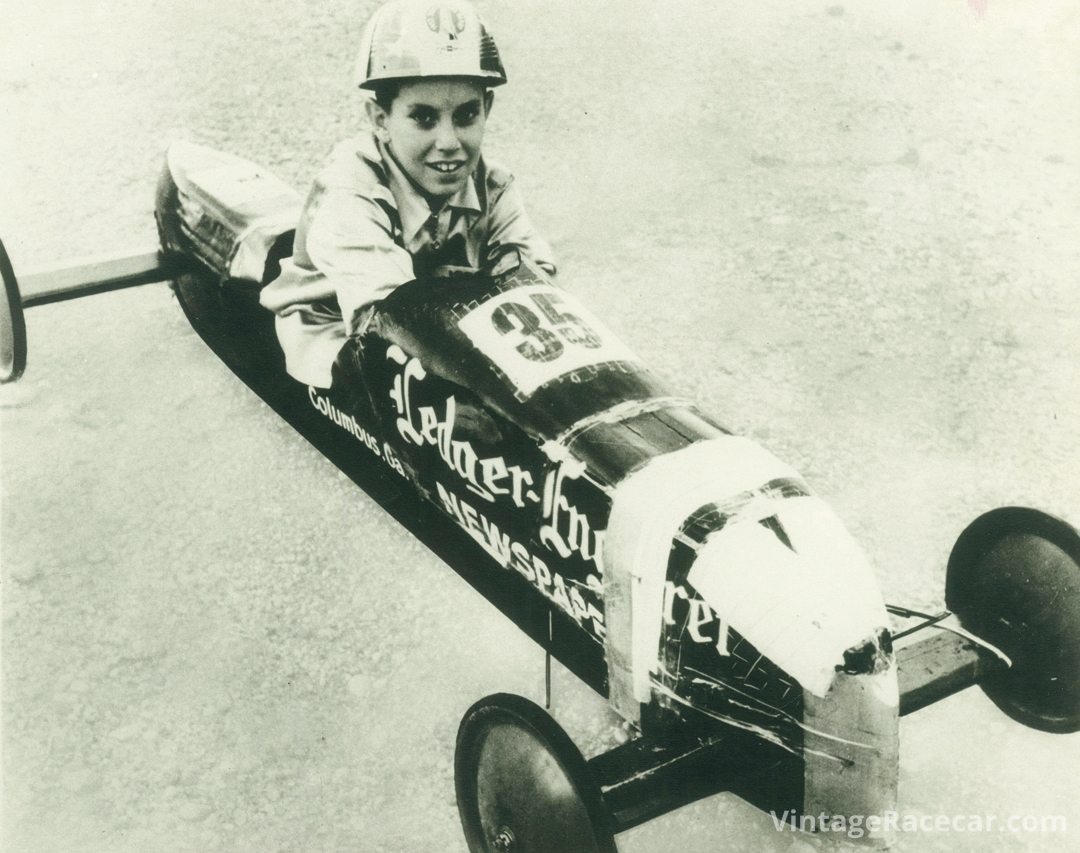

What happened next is undoubtedly the most amazing story in the history of the All-American Soap Box Derby. Lunn continued, “They took me to the first aid station and the medical team patched me up. When I got back to the track the officials told me that I’d crossed the line first and won my heat. There were Derby workers crawling all over my poor car with bailing wire and plastic tape trying to repair it where it’d been split down the middle. They even performed a makeshift repair on the huge hole in the nose using someone’s lunch box. The damaged wheels were also swapped out for a nice set. When they told me I had to go down the hill again, I remember being fairly terrified! I was only 11 at the time and the crash shook me up pretty badly. But the crowd of 60,000 was going berserk. They called me the ‘Ramblin Wreck from Georgia Tech,’ and they were all cheering for me. You can’t imagine how amazing that was for a boy from nowhere, with nothing. I went down that hill four more times with pieces of my car falling off. Somehow I kept crossing the line first, heat after heat, each time by a wider margin. My car was literally disintegrating, but that didn’t seem to slow me down. I beat that kid from Germany, and the race wasn’t even close.”

Then all that was left was the championship race. It was Lunn against Jim Thomas of Williamsport, Pennsylvania, and Victor Shepherd of Flint, Michigan. As the starting plate dropped, Lunn’s pummeled car took a slight lead. Lunn strained to get as low as possible to cheat the wind; the remains of his car surged forward with an ever-widening margin. At the finish, Lunn crossed the line two and a half feet ahead of Thomas, becoming the youngest winner ever and the first winner from the South. And, of course, the roar of the crowd was beyond thunderous!

Lunn’s miraculous victory was heralded in Life magazine. There were parades for him in Thomasville and Columbus. The local Chevrolet dealer paid him $100 a day for personal appearances. And all the kids in school wanted to be his friend. Lunn went on to join the Navy, got married and raised two daughters. The All-American Soap Box Derby went on without him, and Lunn and his car were eventually lost to the sport.

Enter Jeff Iula who grew up around The Derby. His father was a Derby official and Iula even raced in The All-American in 1966. Iula started working full-time for The Derby in 1975 and was the General Manager from 1989 to 2010. One of his lifelong goals was to help establish a Soap Box Derby Hall of Fame. Of course such an institution could not be complete without heavy recognition of Lunn and his car. By 1975, the car had been missing for 15 years and Lunn had been missing for 22 years. Through a series of leads and clues, Iula found the car sitting in the back of someone’s garage. That turned out to be the easy part. The next project for Iula was to find Lunn. Iula asked around, but no one knew what had become of Lunn.

It was generally known that he’d enlisted in the Navy, but that was all. Iula searched for nearly five years, but was never able to locate Lunn…not even a trace. Finally, in 1979 Iula did something bold. He called The Pentagon. After much back and forth he was finally given Joe Lunn’s contact information. One phone call later and they were best friends who had never met.

Iula invited Lunn to be the Parade Marshal for the 1979 race and all the wonderful memories came flooding back. Lunn said, “The Soap Box Derby changed my life. It showed me the big wide world I’d never known about in Thomasville. That experience encouraged me to see the world and join the Navy.”

Iula and Lunn are now great friends. Iula said, “Joe was the Best Man at my wedding. He also saved my life at Charleston Bay in 1982 when the undertow tried to drown me. There was no one else around. If Joe hadn’t pulled me out that would have been the end for me. I thought I was going to that big racetrack in the sky.”

Now 73 years old, Lunn is no longer hidden from the soap box derby community. His car resides in the Soap Box Derby Hall of Fame that his friend, Iula, help to create.

Children dare to dream of fanciful things and adults could learn a few lessons from them. With the Soap Box Derby, there’s always been something for both.