1938 Mercedes-Benz W154

In September 1936, motor racing’s legislative body, the AIACR (Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus), decreed the parameters of the new Grand Prix formula from 1938 onwards. The key elements: a maximum displacement of three litres for supercharged engines, or of 4.5 litres for naturally aspirated units, a minimum weight of 400 or up to 850 kilograms, depending on the engine’s displacement.

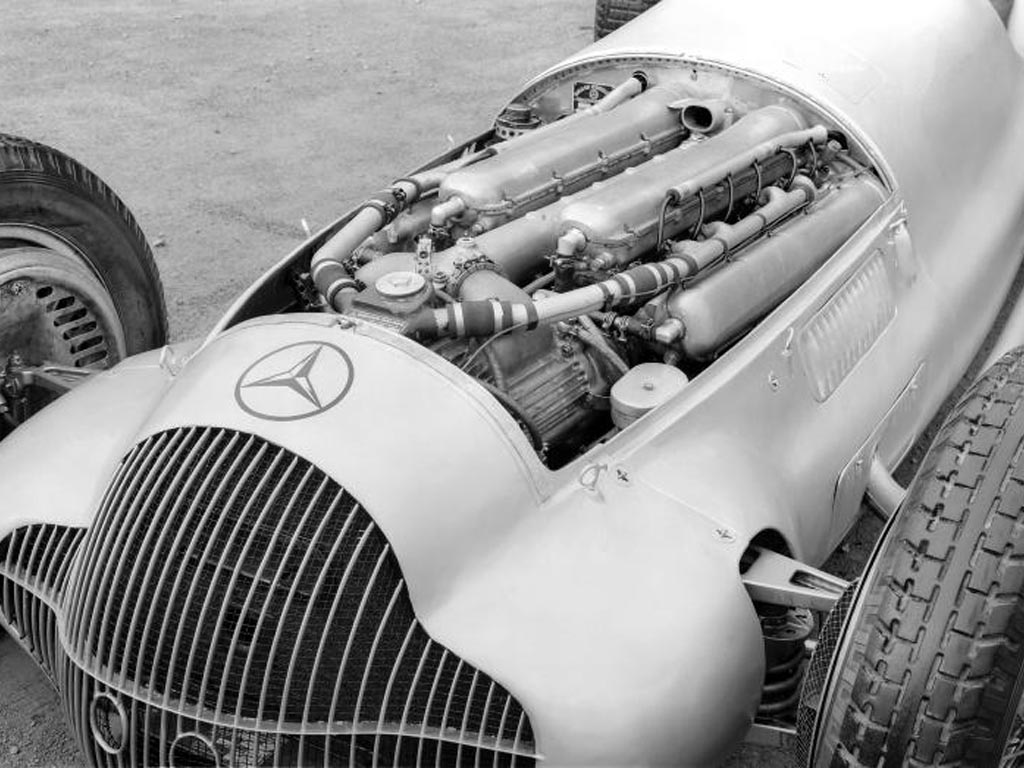

The 1937 season hardly had ended when the Mercedes-Benz engineers were already busy preparing the next with a host of new ideas, concepts and concrete steps. A naturally aspirated engine with three banks of eight cylinders each, i.e., a W 24 configuration, was considered, as were a rear-mounted engine, direct petrol injection and fully streamlined bodies. In the end, above all because of thermal reasons, the engineers opted for a 60-degree V12 developed in-house by specialist Albert Heess. In doing so, with 250 cc per combustion unit, they had again arrived at the minimum displacement in each of the eight cylinders of the supercharged two-litre M 2 L 8 engine of 1924. Glycol as coolant permitted temperatures of up to 125°C. Four overhead camshafts actuated 48 valves via forked rocker arms. Three forged steel cylinders at a time were united within welded-on coolant jackets. The heads were not removable. Powerful pumps pressed 100 litres of oil per minute through the engine which weighed 500 kilograms. Two single-stage superchargers were used initially, to be replaced by a two-stage supercharger in 1939.

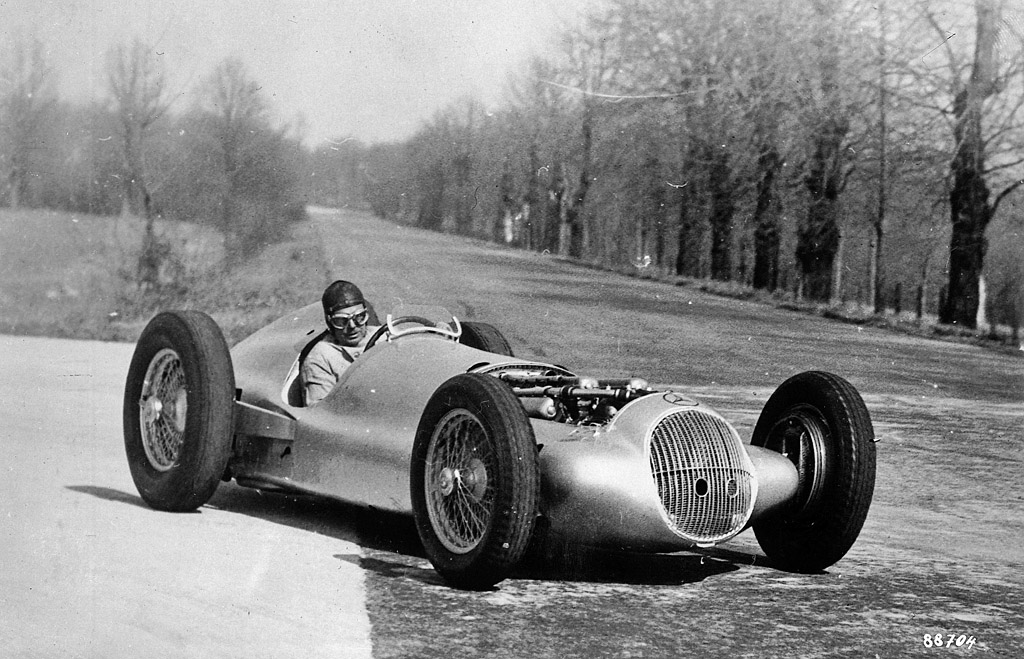

In January 1938 the first specimen was running on the test bench, and the first almost trouble-free test run was completed on February 7, when the engine developed 427 hp (314 kW) at 8000 rpm. In the first half of the season, drivers Caracciola, Lang, von Brauchitsch and Seaman had 430 hp (316 kW) at their disposal, towards its end more than 468 hp (344 kW). In Reims, Hermann Lang’s car was fitted with the most powerful version with 474 hp (349 kW), howling down the long straights of the Champagne circuit at 283 km/h at 7500 rpm in his W 154. And for the first time a Mercedes-Benz racing car had five gears.

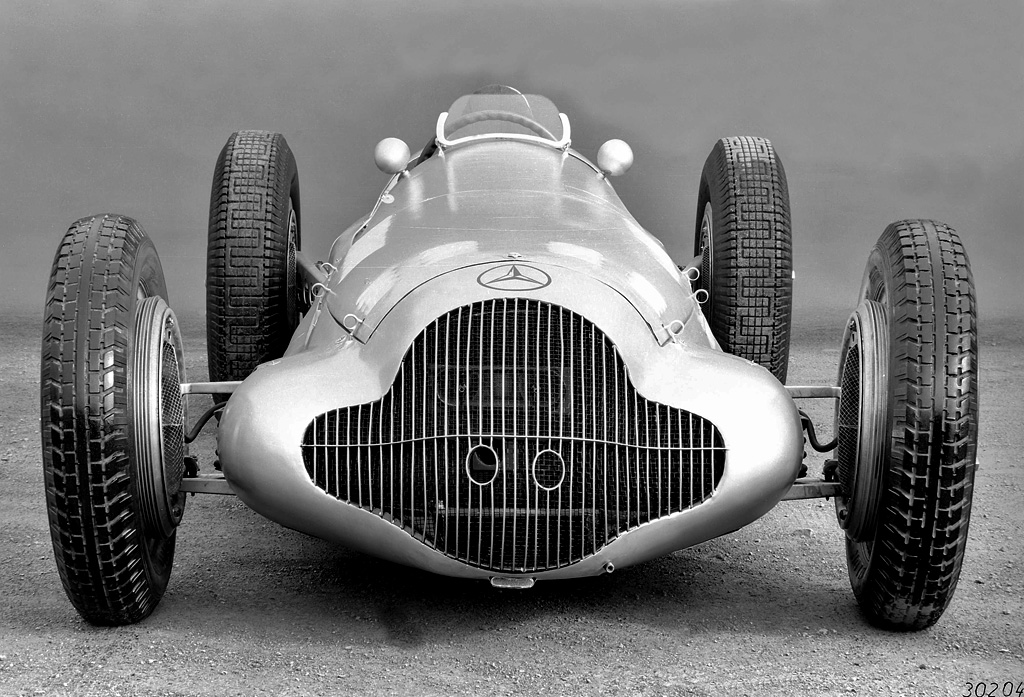

Max Wagner’s task in the suspension design department to come up with a suitable chassis was much easier than that of his colleagues in the engine department. He took over the basic architecture of the previous year’s state-of-the-art solution for the W 125 to a major extent but increased the frame’s torsional stiffness by another 30 percent. The V12 was installed deeply and at an angle, with the carburettors’ air intakes projecting out of the radiator whose grille was progressively broadened before the beginning of the season.

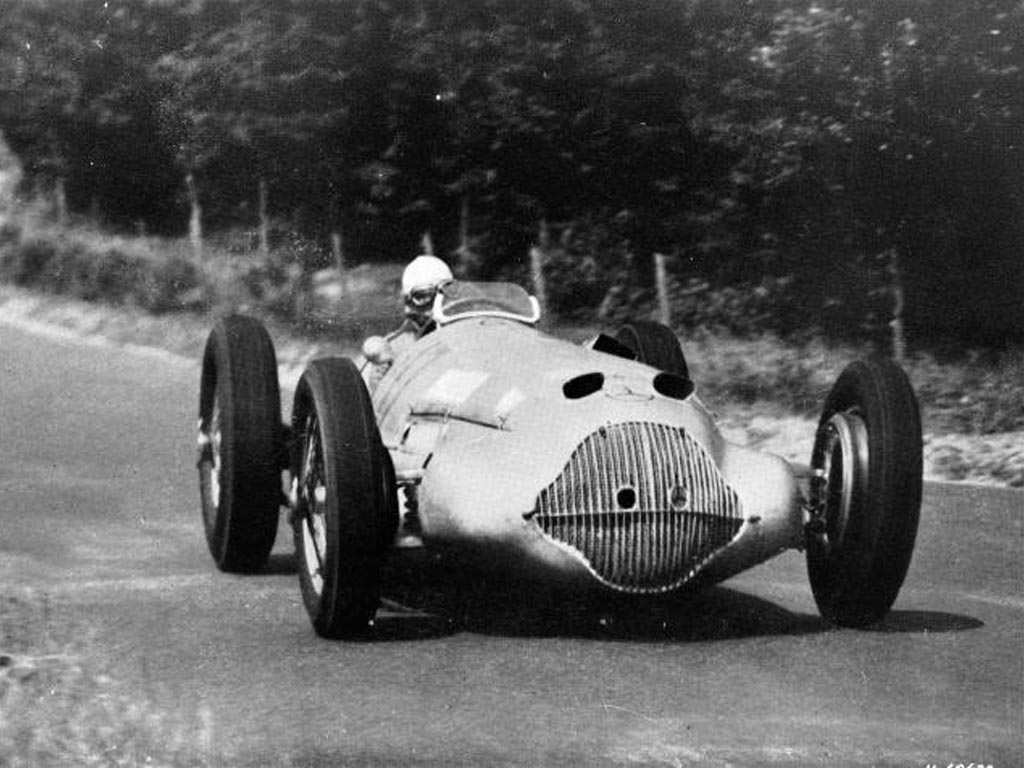

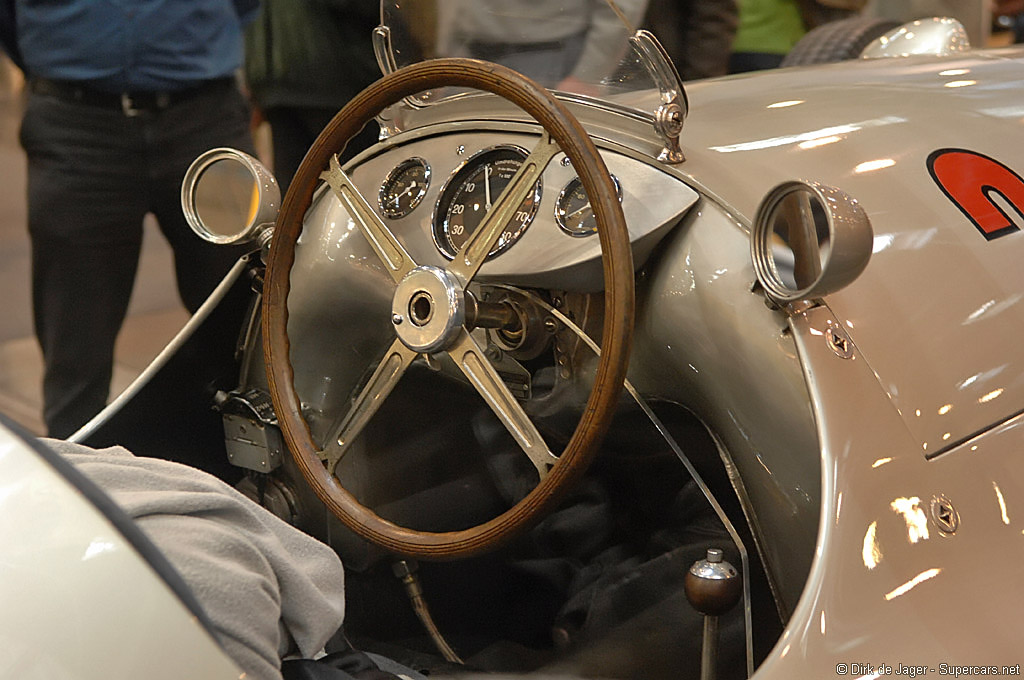

The driver was seated to the right of the propeller shaft. The W 154 cowered close to the tarmac, the body profile being considerably lower than the tops of its tires. This not only endowed it with a visually dynamic appeal but also suitably lowered its centre of gravity. Manfred von Brauchitsch and Richard Seaman, on whose technical expertise Chief Engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut was able to rely, were at once taken with its road-holding qualities.

The W 154 had been the most successful Silver Arrow until that point in time: Rudolf Caracciola clinched the 1938 European champion’s title (a world championship did not yet exist), and the W 154 won three out of four Grand Prix races counting towards the championship.

In order to avoid problems in terms of weight distribution the balance was equalled out by means of a saddle tank above the driver’s legs. In 1939, a two-stage supercharger boosted the V12’s output to 483 hp (355 kW) at 7800 rpm. This engine was now called M 163. The endeavours of AIACR to reduce the open-wheel Grand Prix racing cars’ speeds to acceptable levels had practically failed. The fastest laps, for instance on Bern’s Bremgarten circuit, were almost identical in 1937 (still according to the 750-kg formula) and in 1939 (with the new-generation three-litre cars). In all other respects as well, the W 154 had been refined a great deal over the 1938/39 winter. A higher cowl line in the cockpit area provided greater safety for the driver. A small instrument panel in his direct field of vision was attached to the saddle tank. As usual, it gave only the most essential information, with a large rev counter in the middle, flanked by the gauges for water and oil temperatures. This was entirely in keeping with Uhlenhaut’s principles. The driver, he used to say, must not be distracted by an excess of data.

In Detail

| tags | silver arrow, golden era |

| submitted by | Richard Owen |

| type | Racing Car |

| built at | Stuttgart, Germany |

| engine | M 154/8 60 Degree V12 |

| position | Front Longitudinal |

| valvetrain | DOHC 4 Valves per Cyl |

| displacement | 2963 cc / 180.8 in³ |

| bore | 67 mm / 2.64 in |

| stroke | 70 mm / 2.76 in |

| compression | 7.5:1 |

| power | 349.0 kw / 468 bhp @ 7800 rpm |

| specific output | 157.95 bhp per litre |

| bhp/weight | 477.06 bhp per tonne |

| redline | 8000 |

| body / frame | Aluminum over Oval Tube Frame |

| driven wheels | RWD |

| front tires | 6.5×19 |

| rear tires | 7.0×22 |

| front brakes | Alloy Drums w/Hydrualic Assist |

| rear brakes | Alloy Drums w/Hydrualic Assist |

| steering | Worm & Nut |

| f suspension | Double Wishbones w/Coil Springs, Hydrualic Shock Absorbers |

| r suspension | De Dion Axle w/Tordion Bar Springs, Hydrualic Dampers |

| curb weight | 981 kg / 2163 lbs |

| wheelbase | 2730 mm / 107.5 in |

| front track | 1475 mm / 58.1 in |

| rear track | 1412 mm / 55.6 in |

| length | 4250 mm / 167.3 in |

| width | 1750 mm / 68.9 in |

| height | 1010 mm / 39.8 in |

| transmission | 5-Speed Manual |

| top speed | ~330 kph / 205.1 mph |