Prelude to Excellence

There is a story that the Coventry car company name Alvis originated by taking “Al” from the word aluminum and “vis”, the Latin word for power or force. The supposed author, Geoffrey de Freville, founder of the Aluminum Piston Company, who had commissioned the company’s founding father, T. G. John, to produce a four-cylinder engine using aluminum pistons denied such a story. However, there’s another, which states the word Alvis is a word that is pronounced the same in whatever language it is spoken in. If we take the latter, would it assume that the company was set on producing automobiles to be available in every corner of the globe? To do the latter, those automobiles had to be something special and, looking back, they truly were. In fact, they were probably some of the first to be ascribed with the title “supercar.” The Alvis Car & Engineering Company Limited, or simply Alvis, was certainly on a par with heady names such as Rolls-Royce and Bentley, companies that have always been synonymous with engineering excellence.

Producing high-spec cars had its downside, however, especially during the cash-strapped years of the late 1920s and early 1930s when, similar to more recent times, there was a global recession. It was quite evident from slowing sales and receding finances that Alvis had to address this problem of slow growth, otherwise it would follow a number of other manufacturers of the era and fall into receivership and ultimate obscurity. The company had also devoted much time and finance into front-wheel drive—something French manufacturer Citroën ultimately became master of with its Traction Avant models. The answer for Alvis was reasonably simple; make an affordable car to appeal to a wider motoring community, but keep product standards on a par with the exceptional values they had worked so hard to achieve in previous years. At the same time, Rolls-Royce had purchased Bentley, famed for racing success. And a certain William Lyons—formerly of Blackpool then in Coventry, who produced affordable Austin Seven Swallows—had teamed up with John Black and was now building an inexpensive, sleek, two-seat sports car known as the SS1. Pressure was certainly on Alvis to do something—and quick!

Alvis Chief Engineer and Designer, Captain George Thomas Smith-Clarke, got to work on this new low-cost car. Incidentally, in later life following retirement from Alvis, Capt. Smith-Clarke would go on to make a name in the medical world. While credit for inventing the iron lung must go to Philip Drinker of Harvard University, it was Smith-Clarke, then chairman of a Warwickshire Hospital Management Committee in the UK who, in the 1950s, refined the device making it more user-friendly. It is universally accepted that Smith-Clarke has never really been officially recognized for much of his work as a designer both in the automobile and the medical industries.

Charlesworth Bodies – Founded in Coventry, 1907, by Charles Gray Hill and Charles Sterne the company was one of those that was licensed to build the noted Weymann fabric lightweight bodies, which were also used on early aircraft. Unfortunately, while offering a quieter ride and improved power performance, it offered very little in driver or passenger safety. In 1927, the business was put up for sale and changed tack to produce more traditional metal coachwork. Their particular style of bodywork was curvaceous with a low roofline. While building bodies for Alvis, they also catered for other low-volume manufacturers like Armstrong-Siddeley and Lea Francis, as well as making more bespoke bodies for Bentley. Like many other businesses, with the onset of war the company moved to assisting the war effort, but post-war didn’t seem to have that same momentum and closed its doors in 1950.

Cross & Ellis – Again founded in Coventry in the early part of the 20th century, two workers from Daimler, Harry Cross and Alfred Ellis, founded Cross & Ellis Coachbuilders. They initially produced sidecars for motorcycles, but soon established a rapport with Alvis, building the bodywork for early models such as the 10/30 and the 12/50. Like Charlesworth, they also made bodies for Lea-Francis. During the mid-1930s, they took on work from Hillman, Humber and Wolseley, but price squeezing led to the demise of the company, which eventually went into liquidation in 1938.

Vanden Plas – Of the trio of coachbuilders, Vanden Plas is still today synonymous with luxury and elegance. The company was established in the latter part of the 19th century in Brussels, Belgium, and began making horse-drawn carriages, prior to horseless carriages, under the name Carrosserie Van den Plas. The original company was the brainchild of a blacksmith, Guillaume van den Plas, and his three sons, Antoine, Willy and Henri. Working with prestigious European motor companies, such as De Dion Bouton and Packard, they quickly grew both in stature and style. At the height of employment they had a workforce of around 450 employees in mainland Europe and became renown for producing high class, bespoke bodywork. In England, Warwick Wright first produced bodies for the Belgian company under license in 1917. Like many business deals, timing is crucial, and with the onset of World War I carriage production was changed to aircraft production, but this change of direction left the company struggling in the early 1920s, and the Fox brothers purchased the stricken company in 1923. Although they remained in the suburbs of London the premises were moved from Hendon to Kingsbury and the company began working almost exclusively for Bentley. The years of the Great Depression found the company supplying coachwork to a number of other motor companies, like Rolls-Royce, Daimler and Armstrong Siddeley, as well as Alvis. A certain Charles Follet, a wealthy London based “wheeler-dealer,” racing driver and official, garnered the Alvis deal following a protracted all-night meeting with T.G. John and Capt. Smith-Clarke following earlier discussions at the London Motor Show. Over a period of time, there was much development of the models, but it is safe to say these can be described under two headings, the SA & SB variants and the SC and SD variants.

SA & SB Variants

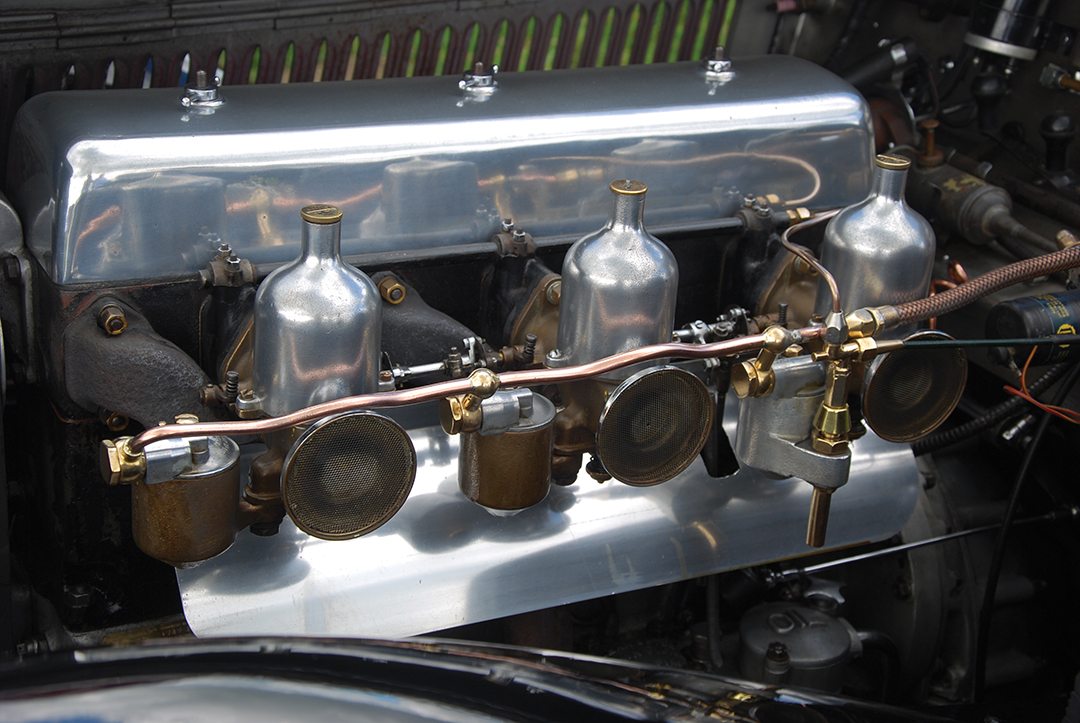

As has been previously mentioned, for economic reasons Smith-Clarke had modified the then current Silver Eagle. The chassis had been lowered, it was equipped with an upgraded version of the six-cylinder engine, including triple HV4 type SU carburetors, dual ignition and a higher-lift camshaft. The engine was also bored out to give a total of 2511-cc and was officially rated at 19.82 hp—thus the Speed 20 name. At that time, like many other countries, British motor engine sizes were taxed according to horsepower. It is said this was to protect the British market from foreign imports, like Ford and Citroën (I made mention of how Andre Citroën navigated this system in the May issue of VR when profiling the Citroën Traction Avant). The engine and gearbox were married and constructed as one unit, which was the first time Alvis had done this. The initial gearbox was a typical “crash” type box with differing ratios for either the sports cars or heavier models. The suspension was by half-elliptical springs damped by Hartford friction shock absorbers, which were underslung at the rear.

The range of this first SA model included 4-seater, four-door, Sports Tourers by Vanden Plas and Charlesworth and a four-door Tourer by Cross & Ellis. The cars gave the usual signature comfortable ride and, dependent on model, could achieve speeds from 75-85 mph. Braking distances were also good with the 14-inch drums capable of stopping in 25 feet at 30 mph. Early signs from press reviews were that Alvis was in good shape. Period publications reported the following: The Tattler – “… civilised motoring for under £1,000.” The Autocar – “It was exhilarating.” Daily Telegraph – “Alvis steering and road holding are up to racing standards.” And lastly the Evening Standard – “A safe, quiet, comfortable car.”

Later SA models went on to offer a Vanden Plas Sports Tourer, a Vanden Plas Saloon and a Vanden Plas four-seater Drophead Coupé. Of course, Alvis simply produced a bare chassis for around £600, so other coachbuilders also built their own particular style of bodywork including, Thrupp & Maberley, the Mayfair Carriage Company, Carlton, Duple and Bertelli.

Some two years later, in October 1933, the SB was launched, again at the London Motor Show. In typical Alvis fashion and striving for perfection, with more time, much better finances and a good platform to work from, Smith-Clarke improved upon his original design. Firstly, the slightly longer chassis was now braced in cruciform style, made of two straight beams placed perpendicular to each other. The cruciform frame overcame the sometimes-poor torsional stiffness of the ladder frame. The cross beams at the front and rear also assisted in carrying the lateral loads from the suspension mounting points. The steering was improved and designed along the lines of the Alvis racing cars of the mid-1920s. A new silent gearbox was fitted with synchromesh on bottom gear. For ease of maintenance, a built-in jacking system was employed and fitted as standard across the range. Lastly, the now signature large Lucas headlamps were standard on all models. Once again, the motoring press widely acclaimed the car, approving the modifications made and the subsequent driving experiences achieved. Improvements were particularly found with both the steering and suspension, which was lighter and smoother, and the suspension now virtually eliminated wheel bounce. The downside to these modifications was added weight, so more power was required.

SC & SD Variants

It is difficult to discern the differences between the SC and SD models of the Speed 20, although the SD is distinguished as the smallest engine version of the Alvis Speed 20 six-cylinder range, while some SC models were fitted with more powerful 3,500-cc engines. These final tinkerings had taken Smith-Clark’s original work to a now well-engineered, innovative and cultured level. With the handling now “sorted” by the inclusion of a new hydraulic suspension system, it was time to increase both power and speed. Not only did the new chassis weight escalate, but also the progressively more elegant coachwork conspired to impair overall engine performance. Improvements to the power were gained by increasing the cubic capacity to 2762-cc and lengthening the stroke from 100 mm to 110 mm, these two modifications increased the rpm. Twin fuel pumps were also added. Charles Follett underlined this new power with two race wins at Brooklands in 1936. Taking a completely standard Vanden Plas Tourer (chassis 11960) he averaged a speed of some 96 mph, with a top speed of a little over 100 mph. Members of the “right crowd” were drawn to this new power and grace, with King Ghazi of Iraq, ship builder Sir Alan Anderson, engineer Denis Foden and actor Leslie Howard being among the elite customers. In all, 289 type SC chassis were built.

By the time the last variation, the SD, was in production more bespoke bodies were being commissioned and other coachbuilders were adding their particular styling to the marque. Carrosserie Vanvooren, an active Parisian coachbuilder, was going through a particular golden decade during the 1930s and bodied an SD (chassis 12779) for the Paris Salon causing a great hullabaloo (it is believed the car still survives today in a private collection in France.) Entertainer George Formby had an SD tailored to his particular requirements by London-based Lancefield Coachworks.

Production and development of the Speed 20 would have continued had it not been for Hitler’s Luftwaffe. On November 14, 1940, during the blitz of Coventry, the entire Alvis works was destroyed. Throughout the war years Alvis re-grouped and, like many UK engineering businesses, assisted with the war effort.

Chassis 12031 – 1935 Speed 20 SC

Our profile car started life in 1935, February 18th to be very precise. Bearing registration plate BNU 409, the Charlesworth bodied car, resplendent in its two-tone grey livery, was despatched to Messrs. Saunders of Buxton where it was used as a director’s car and demonstrator. After some four months, the car was sold to G. Longdon & Sons Limited, Sheffield, and stayed with the company throughout the war years and beyond. During the early 1950s through to 1961, it had a number of Yorkshire resident owners and was sold in a local car auction to a Mr. C.H. Rusk, who kept the car for the next 18 years.

In 1979, new owner Mr. G. Simpkins, undertook the first major restoration of the car. While an amateur, most agree that it was a very professional job involving a number of specialized tradesman, as well as much input from Mr. Simpkins’ hands. It was at this time too, that the car took on its current livery of black and maroon. Following restoration, the car once again went through a number of hands. In 2010, evidence of much work, mainly mechanical, is taken on by the “Red Triangle” company based in Kenilworth, Warwickshire, and known as “The Home of Alvis Cars.” The company services, maintains and produces brand new “continuation” model Alvis cars.

The current owner, a former Formula One mechanic, was drawn to the car by those original design concepts Capt. Smith-Clarke penned over 80 years prior, the flowing lines, the low body and the sleek appearance of this very British car. Like most mechanics, there’s always something to do on a particular car and this is no exception. Apparently, there were two types of steering fitted to this model of Alvis, one was fully adjustable and the other with no adjustment. This particular chassis has the latter, which is in need of attention as there is a little play affecting ultimate performance.

During the 1986 restoration, the rear fenders were not really true to the original, particularly on the curb side. An untrained eye may not pick up on this, but a true connoisseur would instantly see that point. The car was purchased to offer some quintessential 1930s motoring, necessary maintenance and restorative work to a true enthusiast.

Driving the Speed 20 SC

We felt that a vehicle of this stature should be taken to a place commensurate with its highbrow antecedent history. So, we went to a Buckinghamshire village once the administrative center for the royal hunting of the Forest of Bernwood and then property of the Crown. The village also played a part during the period of the English Civil War during the 17th Century, when the Parliamentarians destroyed many of the then royal buildings. For the static shots we park the car in the shadow of an early post mill, probably the best example of such a mill, which has been fully preserved.

The brilliant sunny day, dappled with both light and, at times, heavy cloud are a photographer’s nightmare, but the car stands majestically in place turning the heads of many passers by. While built in the style very typical of top end cars of the era, the first thing that becomes very noticeable is how low the chassis is to the ground in comparison to its contemporaries. Yes, those flowing lines extending the entire length of the car are all apparent. As mass produced, computer-aided designed vehicles pass by, a true statement of elegance and grandeur of a car built by craftsmen of a bygone era is indelibly marked. The front view is dominated by two huge P100 Lucas headlamps, supplemented by a pair of smaller town-use driving lights, that stand sentry-like on either side of the gleaming chrome grille topped with the eye-catching red-triangle logo of the 1930s Alvis brand and an in-flight silver eagle mascot (replacing the original hare design) standing guard-like above.

Opening the heavy driver’s suicide-style door, a whiff of leather and luxury instantly consumes the senses. Taking the seat, the large four-spoke steering wheel fitted with advance and retard controls, hand throttle and light switches holds one’s attention. Feeling for the foot pedals, I’m instantly reminded, left foot clutch, middle pedal accelerator and right foot brake—something the late John Surtees would say to himself time and again as he drove the pre-war Mercedes Grand Prix car, and now something that will ring in my mind for the next few minutes. A central console houses all the relevant dials and buttons including ampere, oil and water gauges, odometer (showing just 74,100 miles), rev counter, ignition switch and starter button—no key start with this car. On the floor, to my left, is the gearshift and to my right a hand brake.

Reading the Speed 20 Instruction Book under the title “Pride in Performance” there is “A Message to the New Owner:” “Because its performance intrigued you, you bought an Alvis. You admired its lithe grace, its air of thoroughbred distinction. But if it had had nothing more than good looks you would have passed it by.” Having admired the grace and style, it’s now time to test performance. Starting the car is reasonably simple, but a necessary order has to be conformed to. First, check the car is in full retard state, set the throttle, pull the choke out about half an inch, this immediately shoots a given amount of fuel directly into the manifold—an early type of direct injection—set the ignition switch to “coil” and then press the button. As soon as the engine comes alive make sure to push in the choke, otherwise the car will be running on too rich a mixture. At this point the car hasn’t burst into life with a big bang, it’s more a question of engaging and offering a reassuring throb or beat, leaving the driver in the sound knowledge that it is ready for action and comfortably able to propel the car. A little more throttle lifts the revs to a satisfactory level. The car remains stationary for around five minutes giving all systems time to warm. With a huge six-cyclinder engine there are copious amounts of oil and water to heat to operating levels.

As we prepare to drive, it is reassuring to know there is synchromesh on all gears, so very similar to driving a more modern car, but REMEMBER the accelerator is in the middle and the brake on the right! Depressing the clutch, selecting first gear and disengaging the handbrake, the wheels are rolling and we begin our journey. Swiftly moving through the gearbox we reach top gear, which can be selected quite early on with this very torquey engine—very similar to the 1929 Invicta I profiled last year. I can feel that slight issue with the steering, but all told the drive is extremely well balanced, neither pulling to the left or the right. From the driver’s view there seems an incredible amount of hood length, and indeed width, as we navigate these almost single-carriageway country roads. Visibility-wise, the screen offers an adequate driving view although there are blind spots, as with vehicles of all eras, but none too detrimental. The car is also very stable and comfortable, those big leaf springs and hydraulic dampers are providing just the ride the designer anticipated. Compared to modern servo-assisted braking systems the Speed 20 feels a little spongy, but given time to get acquainted with it over a small amount of time builds confidence that the car is capable of remarkable stopping distances given its age. Our ride continues, and motoring at around 2,500 revs yields us around 50-55 mph—ample speed for our current surroundings. The torque of the engine is very noticeable when encountering random increases in elevation on the hilly roads.

All too soon the drive is over. It has been an incredibly satisfying experience given it’s a first encounter with an Alvis. It is easy to see how those at Rolls-Royce and Bentley were concerned with the product Alvis was building and the direction it was heading in obvious competition to their models.

With the now almost perfected base of the Speed 20 to work from, the target of a 100 mph road car was not only on the immediate horizon, but very much achievable. If there is a complaint, or rather an observation, to be made with the Speed 20, it is that it’s very heavy and over engineered in many ways. That 100 mph had been reached at Brooklands with a lightweight model of the car, not something the mainstream models were capable of. However, the Speed 25, the next incarnation of the Alvis had more power and delivered exactly the results in performance that Capt. Smith-Clarke was searching for. Once the war was over, Alvis was still ahead of the game continuing in the same vein as pre-war, so I look at the Speed 20 as their prelude to excellence.

Specifications

Engine: Six-cylinder, 2762cc engine with triple SU carburetorsEngine: Six-cylinder, 2762cc engine with triple SU carburetorsGearbox: Four-speed and reverse – synchromesh on all gears.Brakes: Four wheel Alvis 14-inch drum brakes, ribbed for coolingSuspension: Semi-elliptical steel alloy springs front and rear, rear underslung, augmented with tele-control hydraulic shock absorbers.Steering: Rack and pinion – with turning circle of 38 feet.Wheels: Single nut, central fitting wire wheels fitted with 30 x 5¼inch tires.Wheelbase: 123 inchesLength: 180 inchesWidth: 68 inchesHeight: 60 inchesGround clearance: 7 inchesChassis weight: 2,520 pounds